JOHN McVEY’s NOTICINGS

with a micro-interview by Elaine Sexton

interior, stained package delivering water-damaged Rachel Cusk, Kudos (Faber & Faber, 2018)

epigram from the novel’s own epigram, Stevie Smith her “She Got up and Went Away”

ELAINE SEXTON: Tupelo Quarterly featured a wonderful text-based image of yours as the cover of the last issue while we were still discussing this interview. We selected a sampling of images you posted on Instagram over a period of a few days last summer. They appeared to me to be loosely linked by textures and stains. Text and other types of patterns bleed from one to the next. Can you say a few words about your process in photography, work that is not manipulated in the way of the piece we featured on the previous cover of TQ was?

detail, front flyleaf, gutter, Harvard copy of “The Sailor’s Magazine and Seamen’s Friend” 77 (1905)

in which was found : “but because in rough weather scientific observations are impossible”

JOHN McVEY: Lately, I’ve been using instagram to record more in the way of daily noticings, i.e., the afternoon light on a book I’m reading. Some of the earlier Instagram posts — including those you noticed — were recyclings of older images (original or “found”), from my tumblr and elsewhere, where they were generally presented with text of some kind.

scribble/collage, ca 1993; elsewhere on same sheet —

“I took a walk on Spaulding’s farm the other afternoon”

ex H. D. Thoreau, “Walking,” Atlantic Monthly (June 1862)

My method as a photographer? Well, it varies. There are straight photographs (tending toward abstraction), and then screen-grabs of scanning and other errors (e.g., in Google Books), and then photographs of my own drawings in progress, perhaps held up against lamp or sunlight.

detail of mis-scanned photograph of “Cobblestone and brush dam of Fresno Canal, Kings River”

from Harvard copy of USGS Water-supply and Irrigation Papers no 18 (1898)

(since corrected by Google)

With my own photographs, taken out in the world with a camera (or camera equivalent!), I suppose there’s a certain attitude to them: against the grain, only semi-interested in recognizability as “a thing.” I was taking photographs with this attitude as a teenager. Perhaps I knew of Edward Weston then.

Photographs of books are often (not always) from mis- or clumsy scans encountered in Google Books and elsewhere. I will typically be on some kind of search, perhaps for a word or phrase across all texts pre-1923 (the magic, out-of-copyright year), likely in an engineering or science text or journal. An odd or corrupted image would catch my eye, I’d zoom in for a look. If interesting enough, I’d then look for some accompanying text within that same volume, or I might bring something in from whatever I was reading at the time.

I like to relate images (new, old, found, original) to other elements, typically in a dynamic field that also includes at least two different categories of text (poetic, bibliographic). I call this an emblematic relationship (with reference to that Renaissance (but still alive) tradition. The triangulation takes some of the burden of meaning off any particular element, opens it up. These compositions can take me many hours, and even days, to put together. Posting them on tumblr is my way of getting them out of my life. Maybe it’s like being published (although I’ve little or no experience with that, so I wouldn’t know).

detail of poor Google scan of fore-edge and portion of title page,

Fragmente der Moral des Democritus, gesammelt von F.W. Burchard (Minden, 1834)

University of Illinois, Classics Pamphlet Collection, Volume 31-A

I don’t do much manipulation of images. When I do, it generally involves minimal “pumping up” color slightly (via “levels”) or rotating and/or occasionally inverting (positive to negative, typically sepia to cyan). I am careful to note those details in my captions. My images may appear to be manipulated in other ways, but they’re not. I go with the accidental flaws that I find.

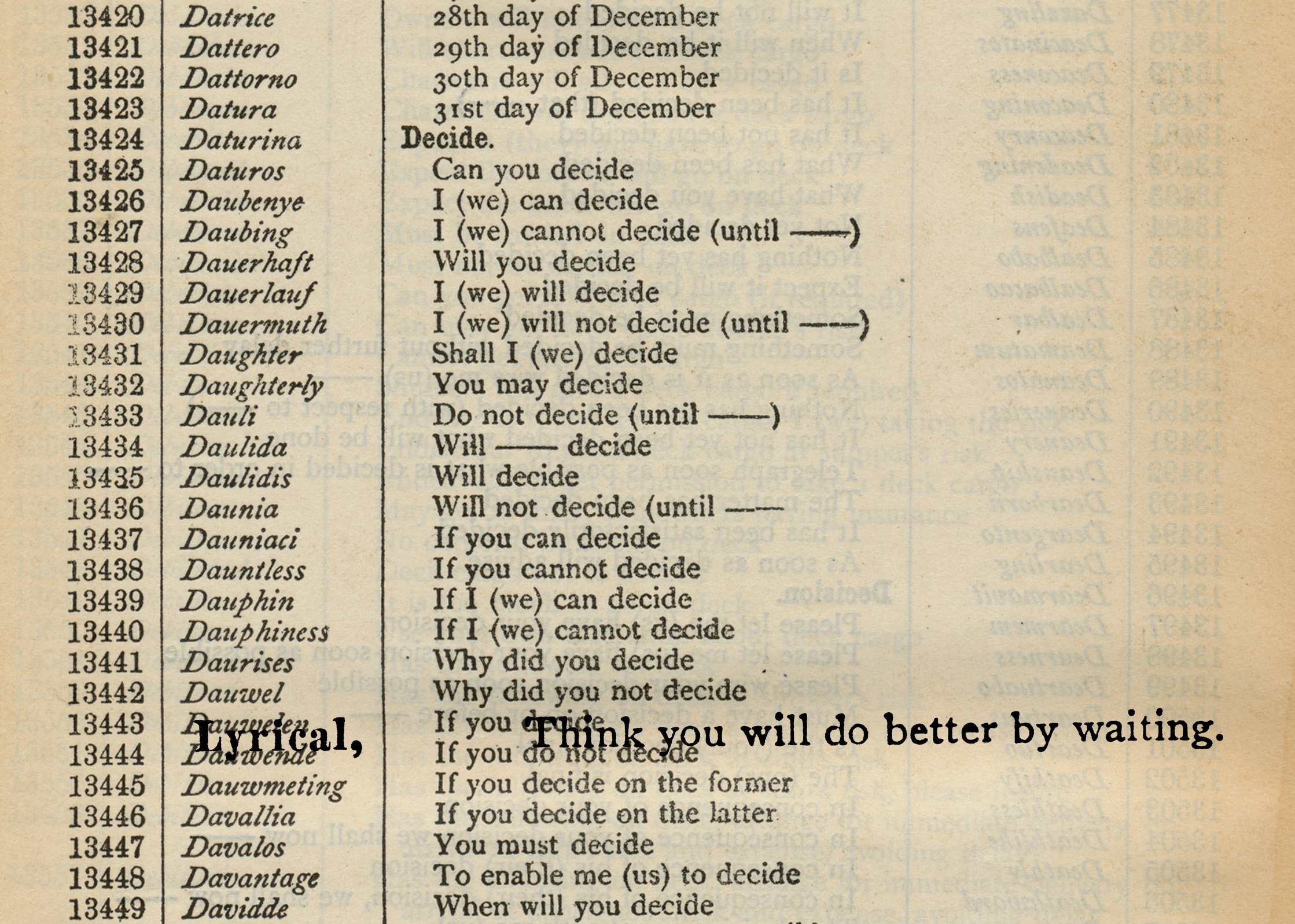

The image you used earlier (one code/phrase line, superimposed on detail of another code) is unusual for me; it was part of a series. I was happy with the way that worked (already 20 years ago!).

collage of text from two telegraphic codes —

The Adams Cable Codex (Third Edition, 1896) and

The ABC Universal Commercial Electric Telegraphic Code (Fifth Edition, 1901)

Working “against the grain” — I mentioned this as an attitude in how I take photographs. It is also an attitude in how I use/misuse texts, that I find in various sources. I tend not to use anything written by myself, concerning myself or my life. Working with derivations from other sources has been a salvation to me, who would otherwise be writing in depressing circles (and circles and circles); occasionally I come upon my own writing of 20, 30, 40 years ago. It is excruciating and unreadable to me.

Maybe now, as I depart from teaching and what has been the center of my life for a while, there’ll be a shift in the margins from which my work has come.

ES: Incidentally, what is the origin of the name of your original tumblr account, aslfatics, of which there are over two thousand images?

JM: As I recall, “asphaltics” was taken.

In very brief, I have long been interested in asphalt, and wrote a poem about it (with a longish bibliographic prelude).

I liked asphalt because of the way it cracks and otherwise degrades, bearing witness to what’s beneath it and, above, the insults of weather and climate and daily usage — its palimpsestual quality. I like the smell of fresh asphalt, and always have done. Asphalt is largely beneath notice — things — human things — happen on it, but it calls attention to itself only when a pothole causes damage.

I liked where asphalt took me: parking lots and engineering texts, but also the work of P. J. M. Larrañaga (and the library of Kings College, Cambridge, to read his correspondence with J. M. Keynes).

A few of my asfaltics posts are tagged “asphalt.”

It sounds dark. something like “obsidian.” But asphalt is not necessarily black. And it lightens with exposure to sunlight; indeed, its photo-sensitive qualities were put to use in early photography —

“In 1826 or 1827, he [Nicéphore Niépce] applied a thin coating of the tar-like material to a pewter plate and took a picture of parts of the buildings and surrounding countryside of his estate, producing what is usually described as the first photograph. It is considered to be the oldest known surviving photograph made in a camera.”

Footnote: this describes one of the ways I have of taking some of my photographs.

“What impressed me was his bodily investigation of the place, a padding, nosing kind of inspection — purposeful and hesitant at the same time.”

— Mowry Baden, “Deeper into the Country.” Essay in Lewis Baltz, Rule without Exception. University of New Mexico Press, 1990 : 67

John McVey has been making images — and things with words — in the margins of his life for many years. His writing shifted into its current trajectory when he began to explore and work with telegraphic code dictionaries over 20 years ago; he has continued to create derivations from codes and other sources ever since, often in combination with found and original images. Other research areas include hardware stores (in art and literature); asphalt (as material and metaphor); and emblematics. He has taught in the foundation and design programs at Montserrat College of Art (Beverly, Massachusetts) since 1994 (and will leave teaching after Fall 2020). Prior to entry into design education, he was a business copywriter/editor in Tokyo, and worked in the antiquarian books business; he grew up in a hardware store. Education: A.B. in English at UC Berkeley (1977); M.A. in South and Southeast Asian Studies (Malay/Indonesian language and literature) at UC Berkeley (1982); and MFA (design) at Massachusetts College of Art (1993). Much of his work can be found via https://jmcvey.net and https://asfaltics.tumblr.com