Maude Tanswai is a writer and visual artist currently based in Los Angeles, originally from suburban Detroit.

VI KHI NAO: In one of your interviews, you stated that you were drawn to healing. If art (or making art) heals, where does it do so?

MAUDE TANSWAI: Based on the detailed nature of my work, the process nurtures complete focus, mindfulness and attention. I find that healing comes from quietness and being still enough to receive and channel energy through various mediums.

VKN: Is chaos, then, the opposite of healing, in your eyes? Have you or your art ever found chaos therapeutic? If so, when or where?

MT: Not exactly the opposite, though it can pose challenges to healing. I accept everything and all change as a natural progression of life, which includes healing. I have found that one heals amidst all types of complicated situations and on several levels. It has been significant to recognize this in the midst of chaos and to trust that the body, the spirit and the mind have not only the ability and strength, but also an indescribable mystical light/energy to prevail. To answer your question, which is a very important one, I have definitely found chaos to be therapeutic, as it is a foundation for awareness. With the benefit of hindsight, chaos has served as a useful counterpoint, a source of deep insight and, subsequently, much inspiration.

VKN: The life of your art has transformed across time. Your earlier work, naturally, depicts the sketches of your neophyte artistic consciousness. Is there a particular piece of yours that you are drawn to? And how would you depict that art piece linguistically?

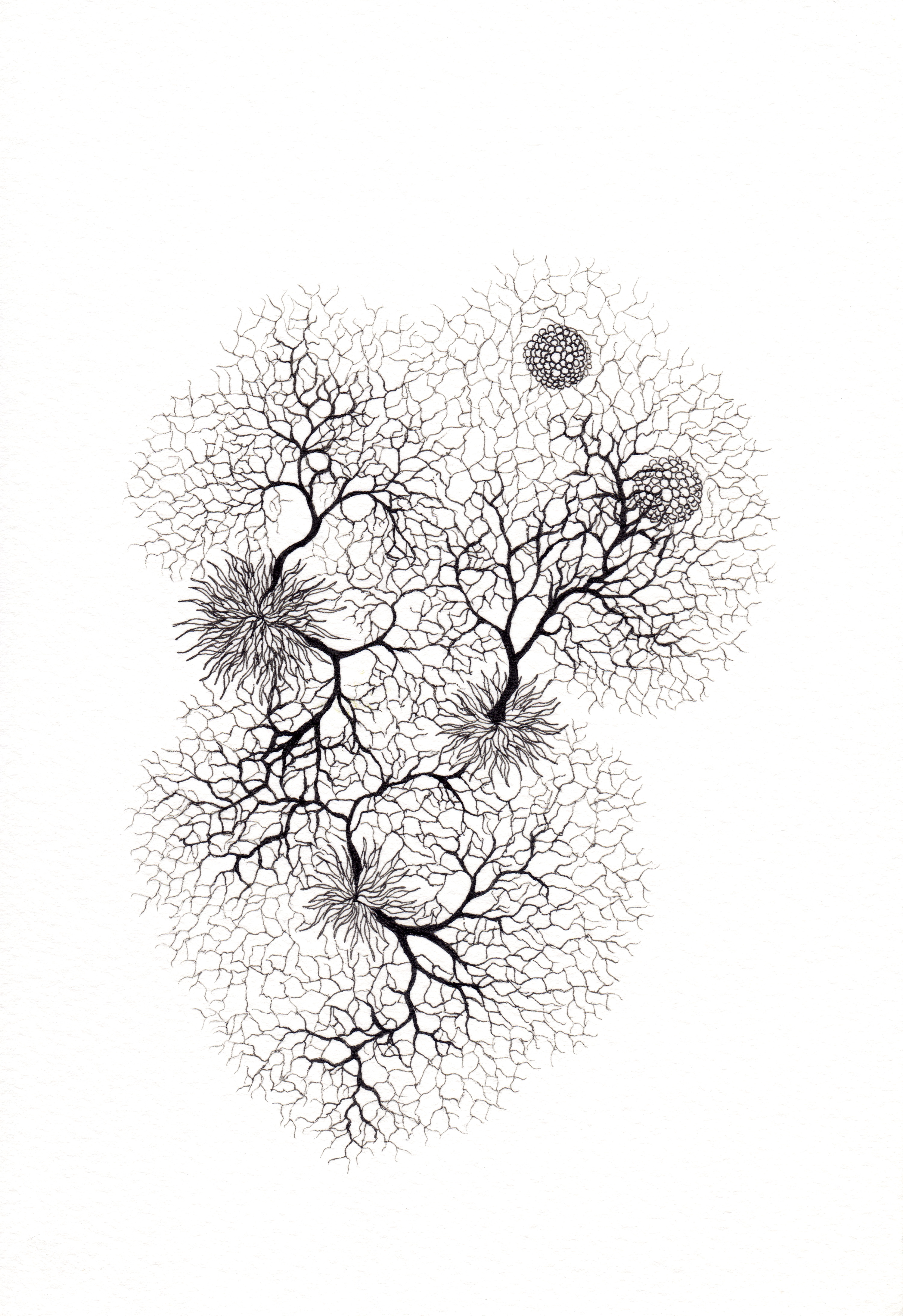

MT: Yes, there is one particular piece which comes to mind that expresses the delicacy of my early endeavors while also divulging an immature yet earnest attempt at articulating an interior vision. It is a biomorphic and fantastical entity that could be found in a forest, in the deep seas, or nowhere at all. You can see elements that show up in later works…root systems, neural pathways, cells, stars, flora, filaments and tendrils. It is awkward, but I still feel tender towards it for its nascent qualities.

VKN: How do you feel after you make an art piece that speaks to your heart and aligns with your consciousness? Whenever I finish an art piece, I am quick to think that I am ready to die. Do you ever feel this way? That art has greeted the cul-de-sac of your life? How do you usually feel after you give birth to a drawing?

MT: Oh dear, I love that you feel that way! I have never thought of it in those terms, but I do know what you mean. I feel a completeness and an equilibrium, a certain lightness and high from having tapped into it.

VKN: In general, are you a fan of contemporary art? Art showcased in contemporary museums such as the MET, SFMOMA etc.? What kind of art repels you? Especially art you have been exposed to—though I welcome imaginary pieces as well, born from your consciousness or the consciousnesses of others.

MT: I am a fan of exploring and supporting all types of contemporary galleries, big and small, as well as larger institutions. I tend to be drawn to smaller works and appreciate the intimacy they encourage; it is challenging to consistently find a considerable amount of smaller-scale art in contemporary museums such as the MET, SFMOMA, etc. While large-scale, expansive work can be moving and powerful, I end up craving greater access to small, detailed, thoughtful artwork in a museum or gallery setting. When it comes to viewing contemporary art, I find most experiences inspiring and provocative on some level. Not all of it always resonates, but I enjoy the feeling that comes with being amidst art, and feeling a deep affinity or feeling deeply repelled, whatever the reason may be. I have undergone periods of extended reclusiveness and incubation, during which time I am not exposed to others’ work. Each time entering each phase feels simultaneously like hibernation and reawakening. These junctures and joints seem to provide amplified sensitivity and heightened access to resonant/repellant reactions.

VKN: For writers and poets, reading can be a function/an intimate aspect/the soulmate of writing. For artists, what do you think is the soulmate of making art?

MT: The soulmate of making art is opening the senses. Consumption and digestion through the senses. Listening, seeing, feeling, smelling... all of it! I realize this is obvious, but I have found it to be the case more often than not. So, for instance, moments of deep curiosity that connect me to experiences, to the natural world, which then lead down the proverbial rabbit hole always and inevitably provide inspiration. Also, reading and writing provide this intimate connection to my visual work as well. Sometimes, all it takes is one word and suddenly I feel profound love and desire to create.

VKN: Could you give me an example of that one word, Maude? Or does it have to be experienced in context? I really love the words “Cà Mau.” It’s a city in Northern Vietnam. Each time I hear that word, I am jolted into a state of procreation/creation.

MT: That is beautiful. “Cà Mau.” The first word that comes to mind in this context is a Thai word pronounced, “Jai.” I understand it to mean heart, mind and spirit. In combination with other words, it can express feeling and emotion with such fullness and accuracy that it becomes nearly untranslatable into English. In these combinations, the words become all-encompassing and heart-wrenching in their power to evoke a specific feeling or concept. Does “Cà Mau” have a meaning?

VKN: I don’t know the etymology of that city, but “cà” is half the word for coffee or a color like an off orange and “mau” means “quick” so literally it could mean fast coffee or fast off-orange, which is quite opposite of how I feel for these two words. Speaking of words, you are also a writer, yes, Maude? From the few autobiological poems I have read, I observe that your literary creation complements your artistic production. When you write and draw, do you view your writing as an extension of your art? Or do you prefer that they superimpose over one another so that they overlap and alter the aesthetical, emotional composition of your holistic creation?

MT: I am still working out the relationship I have with these categories; I feel them both in the same way and hope to express the feeling equally through both mediums so that there is no separation. There is a textual component to my visual work, which might suggest that the writing is an extension of the art, but frankly, I have always thought in words. I visualize words as I hear them, and they trigger thoughts, feelings, visions. Your keenly insightful questions speak directly to an ongoing longing to integrate drawing, painting and writing...to superimpose the literary with the artistic “so that they overlap and alter the aesthetical, emotional composition of a holistic creation.”

VKN: Often, the human population tends to correlate stillness with stagnation. In modern agriculture, it has been observed that one must feed a wolf to keep the grass or wheat interested. Where or who is the “figurative” or “metaphysical” wolf that maintains the balance of your creative ecosystem?

MT: Incredible. I also love this question. I will answer this one with a definition from a vintage medical dictionary:

lupus (lu’pus) [L. “wolf”]

In the Middle Ages, the grotesque appearance of some lupus sufferers brought the myth of werewolves to the minds of people.

These were feared to be human beings who had strange powers to transform themselves into animals.

VKN: At times I find that pain, instead of helping me make art, gets in the way. Can you talk about how having lupus shapes the mental strength of your art? And how does pain, in your drawings for example, express itself in ink (technical pen) as in the shape of a design? Or something else? Less geometrical?

MT: Physical pain is an extremely relevant and ongoing theme in my practice as well as in the art itself. It embeds itself within the drawings in the sense that, depending on whether it is present at the time a certain piece is created, it helps to shape that piece. Sometimes this results in incredibly awkward and foreign work, which I find hard to resonate with (though that renders it more interesting over time for what it represents). That being said, and on the other side, I have also found that I often become unaware of pain as I work. This tends to happen when and if I have found a level of inspiration that enables me to transcend pain itself. Work then becomes an antidote to pain. As with much of my experience with the body and health, the ability to understand and integrate change into my work and life has given me strength and power which I am profoundly grateful for. I find that having intermittent, unpredictable constraints does make the times that I’m able to work that much more precious and sweet.

VKN: Crocheting and knitting are also an extension of your artistic expression. Since it’s more 3-D and kinetic, how is it different from your 2-D pursuits (e.g., drawing writing, etc.)? And what drew you to it in the first place?

MT: The organic nature of the types of fibers I enjoy working with are a major part of the draw for me. Some of my favorite moments in the process that give me intense visceral satisfaction are feeling textures, contemplating colors, considering fiber strength and/or delicacy in relation to function. I also love combining different types of fibers as well as colors; I often work with a combination of cashmere, merino wool, silk and mohair. And more recently, I’ve been drawn to plant fibers that go back to ancient times, such as flax (linen) and hemp. The three-dimensional nature of fiber work feeds my hands in a way that the 2-D does not. In addition, and though several steps removed, there is a manual and mental connection to nature through naturally-derived elements when working with animal and plant fibers, as opposed to synthetic, man-made fibers. I have a deep appreciation for the origins of the fibers and the amount of individual care and attention that goes into spinning the fibers and dyeing the yarn. When I am crocheting, there is a connection between physicality and mindfulness that provides a portal to an even deeper quietness. Through this physical action, the mind becomes mesmerized and is lead to utter stillness.

VKN: You have recently moved into your new home. How will your art change from this evolved feng shui? And, where does your drawing desk face? East, South, West, North? Or is it portable? The landscape of your eyesight?

MT: My desk currently faces North. Thank you for asking! I’m not sure that I would have thought of that otherwise. The sun was just streaming through the windows onto my back, and the natural light in this new space is life-giving. I work at a very large and heavy drafting table, which was facing in the opposite direction over the past week as we were getting settled. Not once did I sit down to work, nor did it feel right to do so. As soon as we were able to move it into this position, I have felt inspired to work, and this is the first session I’ve had to truly think and write at it, so thank you for nurturing the inspiration and blessing the initial stages of work here. It is a dedicated studio surrounded by windows, the first I’ve had with this much natural light. I see trees and shifting sunlight throughout the day, and can also see much of the rest of the home from this spot.

VKN: If you had to choose an animal as an informal companion, not a muse, to sit with you while you make art, would it be leopard or a lion? Or some other animal?

MT: Leopard OR a Lion! Feline energy complements most situations. Fortunately, we have two cats, one of which is part Bengal and so has big cat wildness and energy in him. We have often thought that he moves and acts much like a leopard. The other is a sweet, gentle and lovingly silent creature. We are lucky to have both.

VKN: You are lucky indeed. If you were to make a scarf for that leopard, what kind of fiber or material would you use? Why?

MT: I would have to make it from silk. Imagine the fluid speed of a leopard echoed in the ripple and flutters of a silky scarf.

VKN: Would you include blood as a pigment for your art? If you already have, what was it like?

MT: Yes, I would absolutely consider blood as a pigment. In fact, I have been working to recreate that bloodlike color with inks and paints. I am drawn to the types of colors that our bodies produce; though morbid and somewhat repulsive, I do find the colors of biofluids to be quite evocative and fascinating.

VKN: What is that? Evocative and fascinating....

MT: As literal expressions of our physical bodies and their inner workings, as well as what metaphysically drives us, these fluids, fluids that convey nutrients and life and death and disease and renewal...these colors appeal to me on a visceral level. As indicators and catalysts for change, I find them fascinating.

VKN: What art piece of yours is your favorite? Why is it so? Will you depict that piece using words? Would you like to re-create it again one day? Or do you believe certain things can’t be replicated?

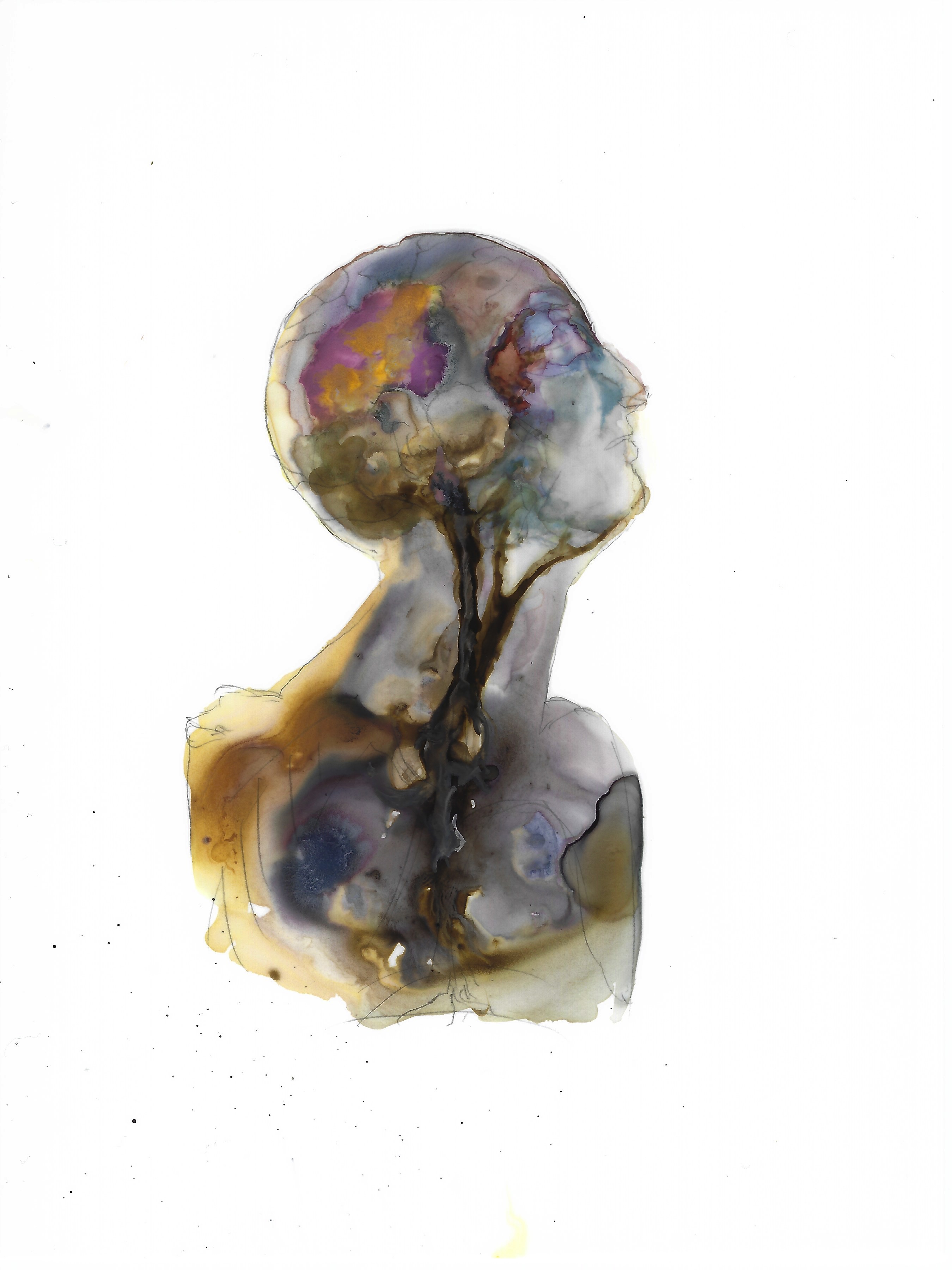

MT: My current favorite is the latest piece that gave me that feeling you remarked on earlier, “Whenever I finish an art piece, I am quick to think that I am ready to die.” I’m just realizing that what we do can be quite insular and singular. How wonderful it would be to witness that moment of pure completeness, of delight. I would love to be in your presence when this is the case. So, my favorite piece is entitled, “Poiesis,” and it came during a session of pure channeling. As it has been described through the ages by countless artists and writers, I truly felt it come through me, not from me. It is one of few figurative pieces I have created; it is a profile of a translucent head looking upwards. The title references the process itself, and speaks to the awe-inspiring power of life.

VKN: Speaking of motion and capture, is there a film in this world that is similar to or is in conversation with your work? What film is that? And would you recommend the observer to watch it before or after viewing your work? Or is the film perhaps so precise and psychologically eloquent in the way it depicts the contents of your creative self that you feel it’s quite unnecessary to view this film at all, since it would purely be an act of futility or redundancy?

MT: Though it has been years since I’ve seen it, “Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East” comes to mind. I’m quite curious if there is a film in this world that is in conversation with your work?

VKN: No, no films yet. But one day. One day, there will be one. Since it requires so much creativity, I used to view kindness as the highest form of art making. What is your definition of kindness, Maude?

MT: That is a lovely view of kindness, Vi. I think that kindness is understanding. When you say that you used to view kindness as the highest form of art making, has it since evolved or changed??

VKN: It has changed drastically. Now, I think humor is....Maude.

MT: Humor is essential. I will be thinking at length now about its role as the highest form of art making.

A Folio of Poems by Maude Tanswai

MAUDE TANSWAI_AUTO-ANAMNESIS_PTS_1&2_TQ_VKN

Vi Khi Nao is the author of Sheep Machine (Black Sun Lit, 2018) and Umbilical Hospital (Press 1913, 2017), and of the short stories collection A Brief Alphabet of Torture, which won FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize in 2016; the novel Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016); and the poetry collection The Old Philosopher, which won the Nightboat Books Prize for Poetry in 2014. Her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. Her stories, poems, and drawings have appeared in NOON, Ploughshares, Black Warrior Review and BOMB, among others. She holds an MFA in fiction from Brown University.