In his well-known speech “I Have No Enemies—My Last Statement,” dated Sept 23, 2009, Liu Xiaobo addressed to his wife Liu Xia this way: “I am in a tangible prison, you are waiting for me in an intangible prison. Your love transcends the high walls and iron bars and touches every inch of my skin and warms every cell in me, allowing me to maintain an internal peace… so that every minute in prison becomes meaningful. And my love for you, full of guilt and apologies, is sometimes heavy, my footsteps stumbling… But my love is firm, sharp, penetrating all barriers. Even if I were to be shattered and crushed, I will embrace you with my ashes.” He continued to say that “in fulfilling the constitutional rights of freedom of speech, and in fulfilling the social responsibilities of a Chinese citizen, I am not guilty for what I have done.” This was part of his self-defense at a trial where Liu Xia was not permitted to be present. He was sentenced to eleven years and died in July of this year while still serving the sentence. The sudden death. The sea burial. Where are his ashes? He had imagined his death and writing poems to Liu Xia from his grave: “Who is disturbing the dead tranquility/in my grave?” But in reality where is his grave?

A prominent “black horse” in the literary scene in China in the 1980s, Liu Xiaobo joined the 1989 movement for democracy, was arrested, lost his teaching job, became a political prisoner, was detained four times, and died a political prisoner.

In contemporary China, prison poetry as a literary genre started in June 1989 when the June 4th student movement was repressed and many participants and supporters were arrested. Another poet whom Liu Xiaobo met through Liu Xia, Liao Yiwu (1958-), was put in prison for writing a long poem about the repression of the movement, titled “Massacre.” Many young students arrested wrote poems while in jail which I have read but I will focus on a few who were established poets before their imprisonment. One thing worth mentioning as background information: Prior to the military crackdown on June 4th, there were protests in May on the Tiananmen Square (Gate to Heavenly Peace) and there were poems written about the protests which were referred to as “spring storms” as poet and poetry critic Luo Yihe had put it:

Low yellow flowers are higher than the tombstones

This year’s spring storms

will seize us.

Everything grows around the heaven,

and even the heaven itself is growing

like a lush pine-forest

growing something called “inseparable.”

It leaves the heaven to be cleaned in the autumn.

Crops will squander on the ground.

I will not harvest—the heaven as witness, so immense

as if all seasons are in.

Autumn will sing, its face lit by our hometown lights:

Spring storms

that will never let us go easily this year.

From “Splendid, suppressed” By Luo Yihe, 5/10/1989

While Liao Yiwu predicted a bloody massacre, Luo Yihe (1961-1989) foresaw tombstones on the Heavenly Peace Avenue in Beijing where he joined the hunger strike on May 13 and died on May 31, the first poet who died because of supporting the 1989 movement. He witnessed the “Splendid” and escaped the suppression by just a few days. Duo Duo witnessed the military clash in the early morning of June 4th and went into exile for fifteen years. In Shanghai, east China, poet Song Lin was arrested. In Wuhan, central China, several poets were arrested. In Sichuan, southwest China, Liao Yiwu and five other poets were arrested. Liao Yiwu was sentenced to four years in prison while the other five poets were released without a trial after two years’ incarceration. As a political prisoner, Liao Yiwu was placed in a big cell with criminals and murderers and was beaten by them sometimes but he also made friends, learned how to play a flute and read with the other inmates.

This is the loveliest hour in prison.

I’m reading Jorge Luis Borges

with you, on death row.

An Argentina moon rises like a good pal

from the left face

of a Chinese prison guard

as if a knife cutting my country into two parts.

From “Reading Borges in Prison” by Liao Yiwu

We argue about death inside our brains.

We argue about death under a fluorescent light.

Shall we kneel down or stand when we die?

Will the bullet shoot through the chest

or the back of our brains?

How is the executioner’s skill? How is his aim?

Which direction will our brains splash?

Are we going to have a chance to look back with a smile

before the soul shoots out?

When the body falls into a hole, with its white ass to the sun,

will the legs stick out, erecting high, like flagpoles?

From “Discussing Death with Death Row Inmates” by Liao Yiwu

Liao Yiwu’s daughter was born six month after he was put in prison, who he wrote many poems for, who he eventually lost due to a divorce.

For My Daughter

Let me sit here in this corner,

the imagined praying cell,

with my hands handcuffed, behind me,

making a sign of the cross

for you, Miao Miao, my daughter.

The little thing that probes and peeks—

I eat you from the dust every day.

The cement sunroof splits: a moon.

I see you on that mountain,

foggy. I see you in a horse saddle.

By Liao Yiwu, 7/1/1991

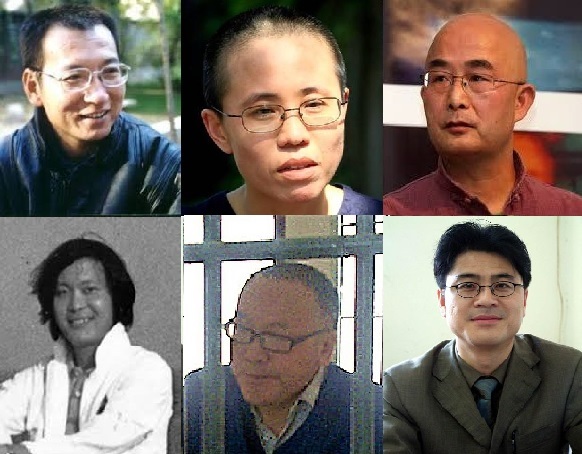

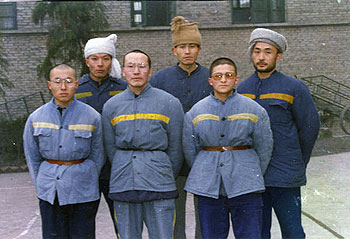

His prison poems were collected and published independently in 2000, introduced by Liu Xiaobo. In the same year, Selected Poems by Liu Xiaobo and Liu Xia was published in Hong Kong, introduced by Zhou Zhongling and Liao Yiwu. Liu Xiaobo was imprisoned four times and died in July, 2017. He escaped from China and has been living in Berlin, in exile, since 2011. Many dissident writers and poets in exile received recognition in Western countries. For instance, Song Lin received a prize for poets in jail in 1992 when he was invited to the Poetry International Festival in Rotterdam that year; Liu Xiaobo (1955-2017) became Nobel Peace Laureate in 2010; Liao Yiwu was awarded the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 2012 and many other awards after that. What Liao Yiwu has been doing is promoting work by unknown poets who are still in prison, one example being Li Bifeng, Liao’s previous inmate, who was sentenced to ten years and later another ten years.

Inmates of No. 3 Prison in Sichuan, in 1993. Li Bifeng in the middle of the front row, Liao Yiwu on the right of the second row.

You are...

A worm wagging in my brain.

Freedom is outside the wall.

Love is outside the wall.

My son is outside the wall.

My mother and my friends are all outside the wall.

I’m in jail.

You’re in my blood.

Your peristaltic waves make me uneasy

but heal me from inside.

By Li Bifeng

Li Befeng (1964-) is a novelist, playwright and poet. Writing gives him the strength to live on after 20 years in prison. Yet he’s so marginalized, still unknown to most people. Shi Tao (1968-), arrested in 2005 and released in 2013, was better known as a poet and journalist because of his Yahoo case (Yahoo exposed his email information to the Chinese authorities.)

My country—when lights go out

When the lights go out,

I extend my hands, and look

at my country—

all the mountains and rivers

are gathered in my small palms.

I put my hands together and meditate—

I see all the darkness from inside out.

By Shi Tao, 8/27/2011

Shi Tao’s wife divorced him due to political pressure. Liu Xiaobo and his first wife TL divorced in 1990 as Liu Xiaobo didn’t want her and their son to suffer because of his imprisonment. After that, Liu Xiaobo found love, strength and inspiration in Liu Xia and wrote many poems and essays when incarcerated again in 1995 and 1996-1999.

Morning

—For Xia

Between the gray walls

and a burst of chopping sounds,

morning comes, bundled and sliced,

and vanishes with the paralyzed souls

of the chopped vegetables.

Light and darkness pass through my pupils.

How do I know the difference?

Sitting in the rust, I can’t tell

if it’s the shine on the shackles in the jail

or the natural light of Nature

from outside the wall.

Daylight betrays everything, the splendid sun

stunned.

Morning stretches and stretches in vain.

You are far away—

but not too far to collect the love

of my night.

By Liu Xiaobo, 6/30/1997

(first appeared in The New York Review of Books, September 2017 Issue)

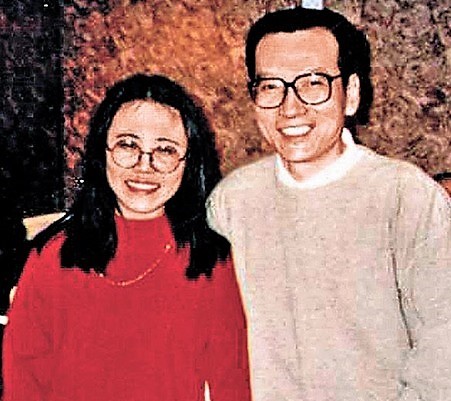

Liu Xia (1961-) met Liu Xiaobo in 1982 in the cafeteria on the campus where his father worked as the university provost. After she moved out of her parents’ apartment, she saw Liu Xiaobo and other literary friends more, and they became bosom-friends. Her short stories were published in the top journals alongside Liu Xiaobo’s literary essays, and her poems appeared in the prominent Poetry Monthly in Beijing. After she witnessed Liu Xiaobo’s involvement in the 1989 movement for democracy, she decided not to publish her work in the mainstream channels anymore.

When Liu Xiaobo was arrested for the third time and sentenced to three years, from October 1996 to October 1999, Liu Xia requested a marriage license from the prison authorities so she could visit him once a month in Dalian prison. They had a simple wedding in February 1996 without getting a marriage license, per Chen Xiaoping, their friend. For three years, she took trains alone each month to visit Xiaobo. She put the 36 train tickets on the wall in her room, a piece of visual art of collage that witnessed her stubborn love for “the enemy of the state.”

A chair and a pipe

wait for you in vain.

No one sees you on the street corner,

in your eyes a bird flying.

A green fruit hangs from a bare tree—

since that morning in the fall,

it refuses to ripen.

A woman with burning eyes

starts to write day and night

with endless dream-words while the bird

in the mirror falls into a deep sleep.

From “Shadow” by Liu Xia, 4.1997

The woman fighting nothingness

with her words

and in the end, was engulfed by the darkness

between her fingers.

From “One Night” by Liu Xia, 4/9/1997

She described her solitude in many of her poems but without self-pity.

I like this moment

when dusk is falling.

Everything around me

dances in uncertain light.

The midday sun and midnight

tears—both silent—have never been

so colorful

as they wander around me.

From “Twilight” by Liu Xia, 4/1998

Liu Xiaobo described her as “the woman more tragic than me” and wrote in another poem:

“Everything is bearable,”

you said to me.

You stare at the sun stubbornly

until blindness grows into a flame

that burns the sea into salt.

My dear, let me say this to you

from the darkness:

Before you enter your tomb,

do not forget to write to me with your ashes.

Do not forget to leave me your address

in the underworld.

From “Endurance—for my wife in suffering”

By Liu Xiaobo, 12/28/1996

Liu Xia was not interested in politics, but supported Liu Xiaobo out of love. She wrote about the June 4th movement of 1989, which ended in tragedy, and grieved the dead on the anniversary date, as Liu Xiaobo did every year:

Those eyes will return tonight.

Those ghosts will return tonight

in the shape of tombstones.

All the ghosts with all those eyes

are gathering here by the candle

speaking to me in a silent dialogue.

The white lilies

start to wither, unnoticed.

Tonight, the night that never ends,

a tree grows out of a tear, and from the tree

many desperate hands are hanging.

From “Dark Night” by Liu Xia, 6/3-4/1997

When Liu Xiaobo was serving his last sentence of eleven years, Liu Xia’s father died in September 2016, and her mother died in April 2017. In deep depression, and unable to tell Liu Xiaobo this, she wrote:

I’m tired.

I’m tired of the white pills.

I’m tired of smiling to you.

I’m tired of the toilets on the trains.

I’m tired of your fame.

I’m tired of my heart getting tired.

From “Untitled” by Liu Xia, 9/2016

In April 2017, when she finally told Liu Xiaobo about her parents’ death and her own condition, Liu Xiaobo was shocked and began to reconsider his decision of staying inside China until death. He agreed to leave China with Liu Xia and her brother Liu Hui.

I’m sick of my life.

that’s ugly. I want to tear

me apart from the ugliness.

I want to escape.

From “Untitled” by Liu Xia, 4/20/2017

Liu Xia sent this short poem with a note to Liao Yiwu in Berlin asking him to help them get out. But things happened so quickly afterwards: news of cancer. Liu Xiaobo died on July 13, still inside China, still serving his sentence. Liu Xia was orphaned and widowed within less than a year.

It hurts to see how Liu Xia has withered, comparing the photo taken on Feb 19, 1996 with thick black hair, and this photo in mourning taken in mid August, 2017. For three years, and then another nine years, she traveled alone by train up northeast to visit her husband in prison, every month, or whenever she was allowed, while suffering from depression, insomnia, and a heart condition. Anyone would have been exhausted. She could have died of the heart condition on the road.

Liu Xiaobo’s final word was to let Liu Xia get out of China. When Liao Yiwu reached her by phone on July 29, Liu Xia told him the last thing Liu Xiaobo said to her on deathbed: “You must get out. Get out [of China].”

Back in 2009, Chinese government had encouraged the Liu couple to go abroad, and live in exile, per Hao Jian, a friend of Liu’s. There were prior “hostage exchanges” in Clinton’s time, when a few 1989 prisoners were released to America. But Liu Xiaobo rejected the offer. He wanted to be part of the dissident force inside China. Liu Xia stayed in order to see him every month. She had other opportunities to leave China, but she knew she would never be able to return had she left while Liu Xiaobo was in prison.

What would have happened to Liu Xia if she had stayed in America when she visited New York City in 1996 for the first time? She was eager to return to China for Liu Xiaobo back then. But now Xiaobo is dead... Many people are concerned about Liu Xia’s current well-being. “Free Liu Xia!” But wouldn’t it be more helpful to send her invitations and help her get out? She will never be truly free in China. Or being free inside China doesn’t really help. Can America invite her over with substantial support such as a residence program and fellowships? She has demonstrated her talent as a poet and artist (even though less than half of her poems and only 6 of her b&w photographs and 0 of her paintings have appeared in the Graywolf bilingual edition.) She needs freedom to continue writing and painting.

Liu Xia has been under house arrest since October 20, 2010. Yet she became a “case” only after Liu Xiaobo died. What does this mean? She becomes important only after her husband is dead? Are family members of dissident writers who are also writers taken less seriously? I recall in 2006, when I was compiling an anthology of the June 4th Poetry, the online information was overwhelming, but there was nothing by Liu Xia. I knew she wrote poems about June 4th, but I just couldn’t get hold of any. In 2009, when I was doing a survey on the “June 4th Poetry of Twenty Years 1989 to 2009”, I found on the internet more than a hundred poems by Liu Xiaobo, but none by Liu Xia. Numerous dissident organizations, including Chinese PEN, who posted Liu Xiaobo’s poems online, knew very well that Liu Xia was also a poet but never cared to make a collection of her work online, or publish a book of her poetry. They compared her to the wives of the Decembrists in Russia. They hailed her as supporter of Liu Xiaobo.

Liu Xia established herself as a poet in 1982, became underground/independent in 1989, and evolved from non-cooperate to resistant, and finally, became a dissident writer in 2009, when she wrote open letters in defense of Liu Xiaobo and his political views. She has been confined in her home for seven years, a prisoner of another kind.

Prison poetry as a literary genre, including writing in prison, jail, labor camps, or under house arrest, and is largely ignored by researchers in China. This work is not necessarily political, even though the prison system is. Prior to 1949, the Nationalist Party sent Communist writers to prison. After the change of power in 1949, it’s the Communist Party that has sent people to prison. Writers and poets who express dissident opinions have been punished and detained by the authorities. The mainstream literary establishment in China, like the diaspora communities, adores the Decembrist uprising in Russia, and the wives of the Russian dissidents, but overshadows its own dissident writers and their wives. Their names are erased in the new editions of anthologies. China loves Marina Tsvetaeva (even though her husband was in the White Army), but ignores the aesthetic merit in Liu Xia’s work. China loves Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Joseph Brodsky, but undermines the artistic power of Liu Xiaobo and Liao Yiwu. The ironic thing: the ancient poets in exile are being praised highly—Qu Yuan, Li Bai (Li Po), and Wang Wei.

**********

Note: Unless otherwise specified, all the poems here are draft translations by Ming Di except that the cited poems or fragments of poems by Liao Yiwu first appeared but in different versions in New Cathay: Contemporary Chinese Poetry (Tupelo Press, 2013) and so did those by Liu Xia dated 1990s in Empty Chairs – Poems by Liu Xia (Graywolf Press, 2015), i.e. Liao Yiwu and Liu Xia’s pieces have been further revised in this essay.