In the titular poem of Heidi Seaborn’s first full-length collection of poetry, the speaker asserts that “sometimes/ Chaos is the way in.” When I turned to the last page to read Seaborn’s biography, I expected the usual poet biography: an MFA, a list of publications, a career as a teacher somewhere. However, Seaborn clearly resists the norm: her biography, as her poem asserts, values the chaos in her life that has guided her to the path of poetry. She’s a world-traveled CEO, she’s moved 27 times, she has three children, and she’s proudly weathered through divorce and grief. All of these themes appear in her collection.

In the titular poem of Heidi Seaborn’s first full-length collection of poetry, the speaker asserts that “sometimes/ Chaos is the way in.” When I turned to the last page to read Seaborn’s biography, I expected the usual poet biography: an MFA, a list of publications, a career as a teacher somewhere. However, Seaborn clearly resists the norm: her biography, as her poem asserts, values the chaos in her life that has guided her to the path of poetry. She’s a world-traveled CEO, she’s moved 27 times, she has three children, and she’s proudly weathered through divorce and grief. All of these themes appear in her collection.

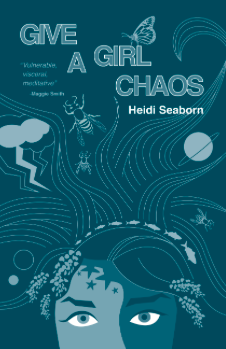

The triumphantly titled Give a Girl Chaosis divided into five sections. Section one details the end of a marriage, as the speaker inwardly examines herself, her partner, and the division of a union amidst health concerns and other personal strife. In section two, the speaker turns outward through a series of postcard poems from all over the world—Nepal, Germany, Turkey, Egypt (to name a few)—and reflects on cultural, historical, and political traumas. In section three, the speaker moves backwards in time, interrogating the wounds of childhood that shape development. Next, the speaker moves forward again, into the domestic sphere and reflecting upon motherhood, nurturing, and love. Finally, the last section is a stunning tribute and meditation on the natural world: in all the brokenness throughout the collection, images of beauty and reverence prevail.

A major surprise in Seaborn’s biography is that she’s only been writing for two years. Given her command of form and language, this is hard to believe. One of the most interesting aspects in her collection is her ability to both honor and subvert traditional forms. In her poem, “Weather,” she utilizes the ghazal form to explore domestic violence, ending with the lines:

“As another storm gathers, day

& night fuse at the horizon—his weather

into a fist, borne by the sea, blowing

your way. You steady for his weather.”

In the tradition of ghazals, which originated in Arabic poetry, common themes include unconditional love, spirituality, or the beauty of love despite pain or loss. This poem turns that idea on its head: this is certainly a poem about love, but it’s a toxic one, a love that endures pain, not one that finds beauty despite it. Also, in the tradition of ghazals, the last couplet includes the author’s name. Seaborn cleverly does this by including the phrase “born by the sea.” Her willingness to make the traditional new embodies the idea that a little chaos can do us good.

Another thing she does well with form is having the shape of the poem reflect the meaning of the poem. In “Se/para/tion,” the words pull apart from each other on the page, resisting the smooth and familiar connection of a sentence or a line, as they detail the end of a marriage. She also uses similes and extended metaphors as perfect reflections of her content and meaning. In “Stung,” the speaker likens marriage to a disturbed wasp’s nest “He too must have glowed,/ until I spoke the words that buzzed around his head, pulled at the fragile/ papery nest of our marriage.” This is a chilling image, one that evokes complex emotions just through the comparison alone.

Furthermore, Seaborn has a marvelous vision of the natural world in all of her poems. Poem after poem, I wished that I could see the world the way she does. Consider these lines in her poem “Beyond”: “Our bed smells of coconut milk. Outside/ the tide washes through splay-fingered/ mangrove roots, leaving a lacy stitch/ with each wave.” The rendering of waves on a shore leaving a “lacy stitch” on the sand is so exquisitely perfect, and it makes the commonplace seem vibrantly new.

These poems are personal in nature, yet it’s impossible not to see the political veins that run through them, especially in regard to feminism. In her examination of motherhood in a poem titled “Girl,” dedicated to her daughter, the speaker ponders her own girlhood:

“I knew nothing then. Not the head-

to-toe sever, rib-to-heart slice

of leavings. Not innuendo’s bee sting.

You, girl with the dimples pressed

by a god’s finger.”

The words “sever” and “slice” point to the violent ways that girls are shaped in their girlhood, to the toxic masculinity and abandonment that nearly breaks them, the “innuendos” of sexual objectification that dehumanize them. And yet, she looks at her daughter’s dimples, a symbol of joy, and sees her perfection, unclouded by the storm on the horizon of growing up as a girl.

In the last section of the book that centers on nature, it’s surprising to come across a poem titled “November 2016,” a date that signals the most surprising, and, for many, devastating American election in recent memory. You wouldn’t expect a poem about Trump to be in a section that largely looks at nature. And yet, there’s no mention of Trump in this poem. There’s no mention of politics or the election. Yet it’s there, haunting the margins. The poem is about her husband building a fence around their garden, but the flowers keep blooming over it and overrunning it, even to the point of crowding the sidewalk and disturbing those who walk past the home.

“Some reach to pluck a bitter flower, take

a bite as they walk on down the road,

their talk of walls and borders, perhaps

just a fence or a bed of nasturtiums.”

Despite the human desire to contain, to separate, to build walls and fences, the flowers will always bloom. Nature will refuse our will. And sometimes it can be beautiful. That is what chaos can do.

Anne Champion is the author of The Good Girl is Always a Ghost (Black Lawrence Press, 2018), She Saints & Holy Profanities (Quarterly West, 2019), Reluctant Mistress (Gold Wake Press, 2013), Book of Levitations (Trembling Pillow Press, 2019), and The Dark Length Home (Noctuary Press, 2017). Her poems have appeared in Verse Daily, Prairie Schooner, Salamander, Crab Orchard Review, Epiphany Magazine, The Pinch, The Greensboro Review, New South, and elsewhere. She was a 2009 Academy of American Poet’s Prize recipient, a Barbara Deming Memorial grant recipient, a 2015 Best of the Net winner, and a Pushcart Prize nominee. She currently teaches writing and literature in Boston, MA.