Befriending one’s pain is the core of Holley M. Hill’s stunning and ravaging memoir — a hybrid of poetry, artwork, journal, and personal artifact that reflects and refracts the painful truth of childhood abuse and abandonment and transforms it into a work of art.

What sets apart Hill’s memoir is the deep love and wisdom that grounds and surrounds the story of her traumatic childhood. Her poems give forth such vivid hues and emotional density I want to say they are what truth looks like polished with beauty, but that implies gems, and they are so much more than that.

They are lyric children begotten of one who stands in openness and fierce vulnerability to nature and the world and the given days of her shattered early life: Agape —from the Greek, meaning selfless, unconditional love. The poem “Heart to Ground” exemplifies this.

What is so striking is the poem’s setting in winter, when ice separates the river the speaker longs for. She lies down upon the ice, both to give warmth and to listen, and is filled with joy when she hears its “chuckling voice.” When spring returns she communes with the river “of the glorious/and comforting/moments we’d shared...” The poem bears quoting in full. Note the charged language of erotic lovemaking, intimate afterglow, and mystical bonding expressed with the innocence of a child.

Heart to Ground

When the snow fell

in soft, supple blankets

it dressed the river

in unfamiliarity.

Being a child who lived

in pockets of the forest

amidst the rippling song

of the river

my body yearned

for the rushing,

beating

current to return.

And so I laid down,

my belly against the ice,

and pressed the hollow

of my ear

into its frigid chest.

I remember the way

my heart felt:

light,

alive,

to hear the chuckling voice

of my dear friend

bending its spine

beneath the woolen coat

of winter.

When spring stripped

the river of its

glossy, ashen sheets,

we spoke in secret

of the glorious

and comforting

moment we’d shared

and how, no matter

what the earth brought forward,

our bodies would always

be together.

There Is Only Lampyridaerises from and charts beyond Adrienne Rich’s great work of feminist archeology, the title poem of Diving into the Wreck:1

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

...

the thing I came for:

The wreck and not the story of the wreck

The thing itself and not the myth.

With the same certitude that Rich descends into the deep to reclaim women’s selfhood, Hill declares in “II”:

Now I lay out my materials, preparing to dig up what I had kept buried for so long.

... Underneath there is a worn-down wooden box and between rotting planks and loose nails huddle the bones of a girl who couldn’t help but lay down in the dark to hide.

Hill purposes her words into poems of such deep passion and vivacity they ignite and catch fire, her senses melding in synesthesia:

My feet

wore a path in that neighbored

forest. Leaves felt my palms,

whipping past them in endless

hours of awe; flashes of magic

blinking like fireflies

as I ran, laughing. A floating light

across the brassy needled floor.

Those leaves feel the breath of

my fingers still, I know it.

This passage is from “The House My Father Built” — a heartbreaking ode shape shifting into elegy. Hill renders the passage of time her father labored as he fashioned their first house into a home:

I watched as he worked,

sun-worn fingers focused

on thick planks as he

pounded and rose

our first set of

bunk beds, his smile

a tin-type memory

I fell asleep to...

as well as foreshadowing its dissolution. Her father leaves the kitchen wall unfinished so he can mark the ages of his children

until the year when

the lines stopped

growing with

- ... when my

mother came back from

the hospital the

first time.

In stark contrast are the journal pieces that chronicle the eight houses Hill and her sisters and brother lived in with their mother in divided divorce-time. Unlike the poems, the titles of these pieces are stark roman numerals.

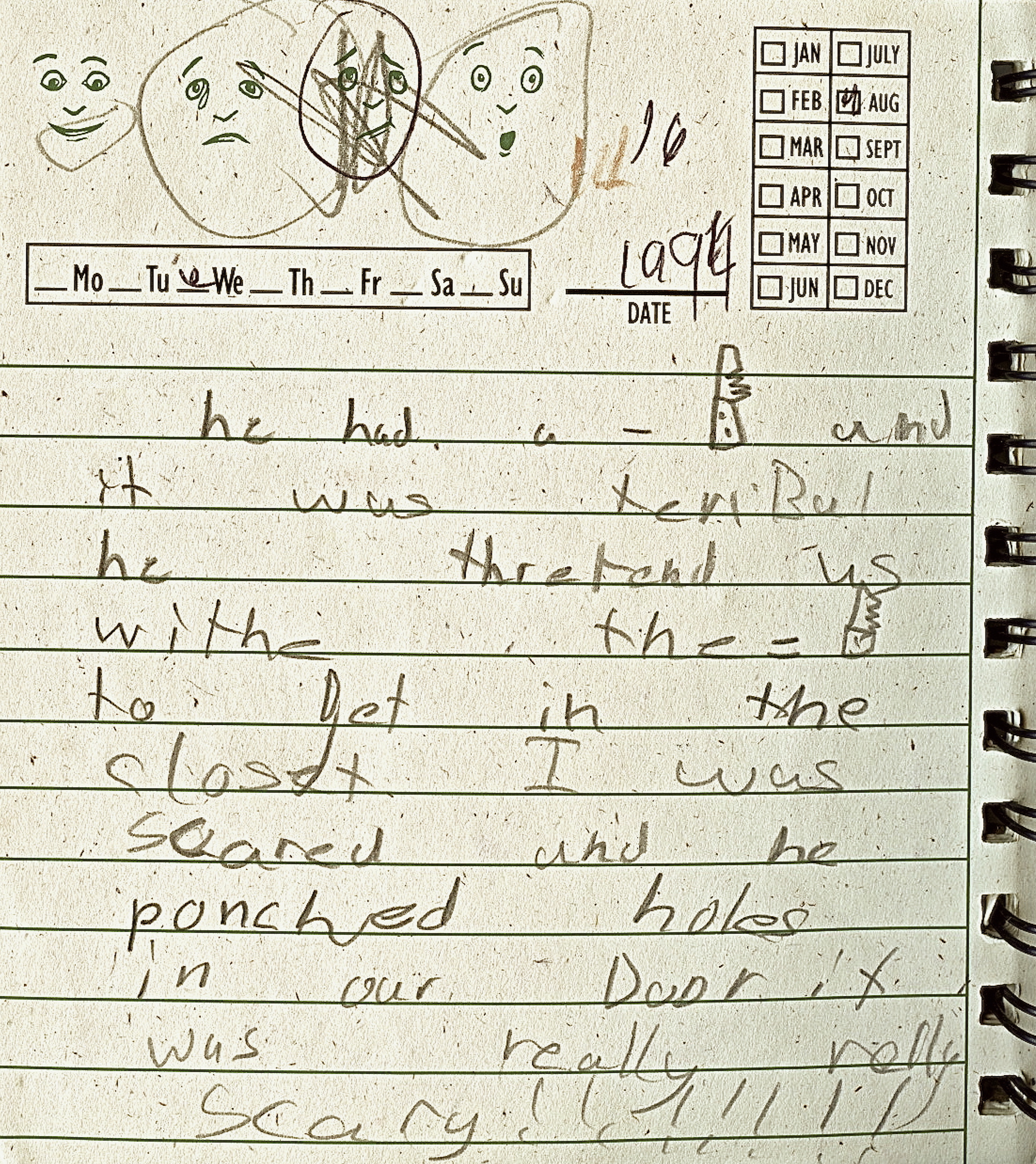

In “III,” she buries the memory of her brother, who could be playful one moment “but in an instant he would turn into a villain and chase us around the house with a butcher knife clamped in his awkward fists, screaming.” Hill inserts an artifact from her childhood, the page from her diary that situates the memory of her brother’s psychotic break in time and place: Tuesday, August 16, 1994.

Within the attempt to describe the terror, the icon of the knife stands in for the word. Its pictorial displacement — the primitive, cave-like scrawl of the knife — bears witness art may be a more cathartic way to process trauma.

In “IV” she buries the fighting, “ [her] parents on top of each other in a screaming, trembling brawl.” In “V” Hill buries the moving. In a condo upstate where her mother has moved to, Hill buries “the last supper she put together right before she sat us all down and told us she was going to kill herself and we would never see her again.”

Ten numeral-entries chronicle the suffering of Hill and her siblings as they move through a succession of eight houses. They represent their emotional state and the burden of burying the war at home every day when they must go forth to school.

They stand alone — like tombstones — the numerals evocative of the words chiseled into them. They are obituaries — grim reckonings of her life at a given time, and mortuaries — autopsies of the horror that happened in the houses she lived. This is audacious work: Hill’s ability to perform two contrary acts at the same time — burials and exhumations — and reconcile them with clear eyes and a patient heart.

“We are, I am, you are / by cowardice or courage / the one who find our way / back to this scene,”2— the wreck and the wreckage — concludes Rich in her poem. There Is Only Lampyridaeis a work of supreme courage. Hill has fashioned in the crucible of her suffering a work of beauty and awe.

However, what transforms this memoir is the inclusion of the artwork. As stated in the Preface: A Voice Made of Paper and the Past, “Taking inspiration from nature and events in her childhood, [Holley] has pieced together landscapes and otherworldly places to reflect visions of home, family, growth, and healing.” The artwork is the gold that welds the shards of this memoir back to wholeness, a vessel restored that can receive what life has to offer again, and the greater gift, to pour it forth and share. Nina Alvarez’s vision and dedication to hybrid books situates Cosmographia at the vanguard of the publishing industry.

Notes

- Adrienne Rich, Diving into the Wreck. (W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. New York, 1973)

- Ibid.

Richard Cambridge is the author of a collection of poetry, PULSA—A Book of Books, (Hanover Press), and the one-person theatre production, The Cigarette Papers. He is a fellow emeritus at the Black Earth Institute, a progressive think tank based in Wisconsin, and edited their online journal, About Place: 1963-2013—A Civil Rights Retrospective. He is the poetry editor for The Lunar Calendar, and reviews and interviews for the online journal, Solstice Literary Magazine. He has an MFA in Fiction from Stonecoast at the University of So. Maine.