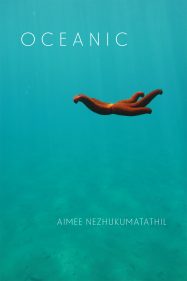

In Oceanic, her fourth collection of poetry, Aimee Nezhukumatathil writes a series of love letters to the world and its inhabitants. From intimate psalms of love to her husband—whose love wields electricity as they ascend the Swiss Alps—to poems addressed to starfish, turtles, and the Northern Lights, the “you” in each poem is as fluid and varied as the structures she uses to encapsulate all subjects. The tender, introspective “Self-Portrait as Scallop” and “The Two Times I Loved You on a Farm” carry the eye in a wavelike rhythm with lines spaced elegantly across the landscape of the page, while poems like “Upon Hearing the News You Buried Our Dog” showcase her adroitly crafted couplets. Marine biology, feathers, flight, passion—these thread her poems in a cohesive arc firmly planting the speaker in a world that demands unflinching attention. With her signature language whose register is both lyric and conversational, sonic lines rich with seamless pairings of sound and dynamic imagery, in bold and yet vulnerable sincerity she observes and ponders the marriage of science and love—the double star Albireo whose blue and gold entities melding into one she refashions into the oneness of romance, or the “underwater volcanoes” and “pillow lava” that give a night of passion a geography, a second physicality. Touching upon familiar themes of identity and placement that recall her earlier works, Nezhukumatathil invites the world to see “the dark sky as oceanic, boundless, limitless— ... / Let’s listen / how this planet hums with so much wing, fur, and fin.”

In Oceanic, her fourth collection of poetry, Aimee Nezhukumatathil writes a series of love letters to the world and its inhabitants. From intimate psalms of love to her husband—whose love wields electricity as they ascend the Swiss Alps—to poems addressed to starfish, turtles, and the Northern Lights, the “you” in each poem is as fluid and varied as the structures she uses to encapsulate all subjects. The tender, introspective “Self-Portrait as Scallop” and “The Two Times I Loved You on a Farm” carry the eye in a wavelike rhythm with lines spaced elegantly across the landscape of the page, while poems like “Upon Hearing the News You Buried Our Dog” showcase her adroitly crafted couplets. Marine biology, feathers, flight, passion—these thread her poems in a cohesive arc firmly planting the speaker in a world that demands unflinching attention. With her signature language whose register is both lyric and conversational, sonic lines rich with seamless pairings of sound and dynamic imagery, in bold and yet vulnerable sincerity she observes and ponders the marriage of science and love—the double star Albireo whose blue and gold entities melding into one she refashions into the oneness of romance, or the “underwater volcanoes” and “pillow lava” that give a night of passion a geography, a second physicality. Touching upon familiar themes of identity and placement that recall her earlier works, Nezhukumatathil invites the world to see “the dark sky as oceanic, boundless, limitless— ... / Let’s listen / how this planet hums with so much wing, fur, and fin.”

Early in Oceanic, Nezhukumatathil reintroduces the theme of multicultural identity and couples the grace of girlhood with the violence of being carved into Otherness. “On Listening to Your Teacher Take Attendance” is an address, a guide, to the child whose teacher eviscerates the pronunciation of her non-western name. Nezhukumatathil creates a theater of discomfort and sterility, meshing the smells of “fake-lemon antiseptic” with “freshly soaped necks / and armpits.” She focuses on the brutality of a butchered name with the vivid image of a bloody sausage casing trapped between her teacher’s teeth as he fumbles awkwardly with “a white, sloppy apron.” At once the class turns, anticipating a reaction, but the child resists the further objectification of being exhibited and scrutinized. The speaker, who begins the poem with the instruction, “Breathe deep,” now guides the child into a meditation of seawater. The child is drawn into a reprieve, a halcyon memory of traveling with her family, who:

took you to the China Sea and you sank

your face in it to gaze at baby clams and sea stars...

Here Nezhukumatathil uses alliteration, the soft “s” binding together a sea image. The face that the classmates crane to see is now buried in gentle water. The speaker bids her to consider this, to remember the tender innocence of her classmates being toweled dry and dressed for school before she juxtaposes this with an image of a handheld pencil sharpener and its tiny blade. Even the children are culpable of this butchery, their transient innocence halted in school, where they are discovered to be capable of the handheld violence of misunderstanding and distancing.

In contrast, her elegiac tribute to a more understanding teacher in “Mr. Cass and the Crustaceans” celebrates the shared love of science that also created a safe space for identity. As “the only brown girl / in the classroom,” the child—this time the speaker, no longer being held at arm’s length, but free to invite the reader into her psyche—once again places her face in water to take in the life beneath its surface. This time, it is not an act of escape, but of engagement. Her teacher’s invitation to “listen”—to water, but also to the intuitive introspection that sinking one’s face into water evokes—empowers the no-longer-bridled woman whose feet are planted on two continents. “In Praise of My Manicure” is a bold, flamboyant celebration of “blending out.” Unconcerned with the hapless task of fitting in, the speaker connects the world in a network of interrelations, likening herself to preschoolers in a rainstorm, coins in a fountain, red starfish, Kathakali dancers, as she paints her nails and thus effects a posture to scare and to dazzle. “You’ll never be able to catch my pulse, my shine,” she dares the reader.

This bridges the core topic that Oceanic as a whole explores: the discovery of life in all its forms. Nezhukumatathil’s “Invitation” cocks an ear to the planet’s hum with wing, fur, and fin—a wing she later covets in “Love in the Time of Swine Flu”—and a hum to which she returns in “I Could Be a Whale Shark.” Round with pregnancy, the speaker once again enters the China Sea, now established as a threshold for transformation. Here she is transforming into a mother, through the physicality of pregnancy moles and voracious appetite—and both feeling the life within her and fearing the sting of the jellyfish, she ponders again the “humming on this soft earth.” In doing so, she assigns sound to the mystery of life—the time it takes to eat pizza or hear a heartbeat, to create an ocean or shift Los Angeles north, and at the very bottom, she discovers a bee. The reverie of time she chronicles as a declaration of love, the infinite number of events that her love for “you” will outlast. Her Dickinsonian bee reemerges in another love poem, equally surreal in its likening her separation from her beloved to winning second place in a bee-wearing contest. She loses to a guy completely covered “in hum.” The motif of humming has transformed the very word, so that verb becomes object. It is no longer something to hear passively; it is a garment to wear, to cover oneself completely.

Oceanic is a story of restoration, and the end goal is love. The heroes and victims of “The Falling: Four Who Have Intentionally Plunged Over Niagara Falls with the Hope of Surviving,” in which she channels the different personas with varied structures, considers the happiness of the discovered severed arm or the tender companionship of George Strathakis’ pet turtle. The scar from her C-Section she refashions in a self-portrait as a second smile; the blade of her classmates’ pencil sharpener she repurposes as a signifier of love and sex in the shared knife that awakens desire in “This Sugar,” and in “Aubade with Cutlery and Crickets,” in which the allure of her lover is likened to the smell of knives and the movement of blades. She gathers the vast geographies of the world together in a collective theater, as her poems sweep across Singapore, the Philippines, China, India, Switzerland, and the United States. Her found poems manifest the clumsy—and her “Inside the Cloud Forest Dome” showcase a more graceful recovery of—misunderstandings in cross-cultural encounters and the beauty of each place in its sense of wonder, in the life it holds, as “My South,” taken from Whitman, hearkens on a classic Nezhukumatathil theme: land in regards to love. Aimee Nezhukumatathil in her South, and Aimee Nezhukumatathil issuing a prayer for her family in an ascending plane or stretching her body across the limber surface of the China Sea, celebrates her world and the renewing act of falling in love with it.

Shannon Nakai has published work in Kaye Linden’s 35 Tips for Writing Powerful Prose Poems, The Bacopa Literary Review, River City Poetry, and others. She has an MFA in Creative Writing in Poetry from Wichita State University, where she also teaches English. A former Fulbright Scholar in Turkey, she currently lives with her husband in central Kansas.