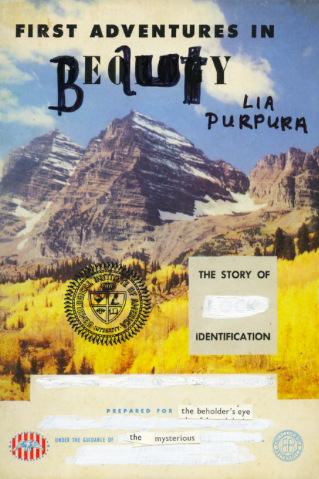

“Once, a friend reacting to a tickle on her arm, saw she had smacked a lacewing—green filigreed and sheer as a breath. ‘You’re so beautiful, I’m sorry,’ she said, before finishing it off. As if its beauty might have saved it.” So begins Lia Purpura’s First Adventures in Beauty, published in 2016 in a limited print run edition and made available this year as an eBook by the experimental indie outfit, See Double Press. An experiment with collage, erasure, essay, and poetry, the book expands on territory Purpura has explored in her previous eight collections of poetry and essays. The net effect of this creative inmixing reads as much as a meditative art object as it does a book. Purpura’s lyrical bursts of insight and anecdote appear over the pages of a children’s geology textbook treated with a heavy layer of whiteout, save for the instances in which she leaves short passages unobscured. This selective erasure offers a poignant tonal counterpoint to Purpura’s moving examination of beauty and disgust. Amid a treatise on common perceptions of slugs in which Purpura observes, “A slug also catches the eye, refracting sunlight like a prismy tear—which we meet with no desire at all—no urge to scoop up and place under a silvery leaf,” appears an unredacted portion of her source text that reads simply: “a specimen that does not fit the description.” Purpura draws attention to this moment by framing the unredacted text with cut-out images of a scorpion fly on one side and a hummingbird on the other.

“Once, a friend reacting to a tickle on her arm, saw she had smacked a lacewing—green filigreed and sheer as a breath. ‘You’re so beautiful, I’m sorry,’ she said, before finishing it off. As if its beauty might have saved it.” So begins Lia Purpura’s First Adventures in Beauty, published in 2016 in a limited print run edition and made available this year as an eBook by the experimental indie outfit, See Double Press. An experiment with collage, erasure, essay, and poetry, the book expands on territory Purpura has explored in her previous eight collections of poetry and essays. The net effect of this creative inmixing reads as much as a meditative art object as it does a book. Purpura’s lyrical bursts of insight and anecdote appear over the pages of a children’s geology textbook treated with a heavy layer of whiteout, save for the instances in which she leaves short passages unobscured. This selective erasure offers a poignant tonal counterpoint to Purpura’s moving examination of beauty and disgust. Amid a treatise on common perceptions of slugs in which Purpura observes, “A slug also catches the eye, refracting sunlight like a prismy tear—which we meet with no desire at all—no urge to scoop up and place under a silvery leaf,” appears an unredacted portion of her source text that reads simply: “a specimen that does not fit the description.” Purpura draws attention to this moment by framing the unredacted text with cut-out images of a scorpion fly on one side and a hummingbird on the other.

Purpura’s arguments develop over the course of several pages at a time, clearing space for her reader to meditate upon her use of image, erasure, and their relationship to her handwritten text. In a particularly stirring passage, Purpura suggests that “it’s not the beautiful’s need to be cared for, but its independence that beckons and holds us.” Over the following seven pages, we are presented with a series of mostly whited-out surfaces upon which Purpura lays out a moving rhetorical conceit amid various collagist images meant to guide and expand our readerly associations. “The beautiful possess an abundance of form—color—scent—gesture, and with more than enough, the beautiful’s sufficient unto itself,” writes Purpura amid cutouts of black and white images depicting the natural world, then a cherub, then a rock quarry as it’s mined by a team of workers. As we near the end of this movement, we encounter a page adorned with the cutout image of a dragonfly juxtaposed next to a textbook photo of Ingres’s The Source, pasted in the upper left-hand corner of the page. Ingres’s painting depicts a young girl standing nude, smiling with both hands above her head as she lets water pour onto the ground from a pitcher that rests on her shoulder. On the next page, again pasted in the upper left-hand corner, Purpura presents a refrain of sorts as we see a photograph of another woman standing nude before the camera, forcing us to reconsider our initial perception of these images. The text that sprawls past and between both figures continues: “And looking on, soaking, gathering it in—it’s we who are fed on its plenty. Thus inessential, extraneous to it, like any discounted lover, we’re moved, compelled even, to sidle up and be near.” In her description of this sidling up, Purpura evokes Rilke: “beauty is the beginning of a terror we are just able to bear.”

If Purpura’s presentation in First Adventures in Beauty is a departure from her previous work, her readers should be relieved to know that her broader outlook remains intact. That is, her willingness to linger in uncomfortable spaces, fixing an absorbent gaze upon the forbidden. What she returns with feel like answers. Even as she avails herself of a broader range of expression, the intellect we encounter in First Adventures in Beauty derives from the same locus as the voice in Purpura’s more formally conventional work. Take, for example, her essay “Autopsy Report” which opens her 2007 collection, On Looking (Sarabande, 2006), in which Purpura observes the body as it is rarely seen: “I shall begin with the chests of drowned men, bound with ropes and diesel-slicked. Their ears sludge-filled. Their legs mud-smeared.” Set during a visit to her local morgue, the essay shows Purpura perfectly content, even a giddy, to dwell in a space that others may find revolting: “The calm came to me while the skin behind the ears and across the base of the skull was cut from its bluish integument. While the scalp was folded up and over the face like a towel, like a compress draped over sore eyes.” This image reemerges at the end of the essay as Purpura notices her fellow shoppers at the grocery store: “I saw all the scalps turned over faces, everyone’s face made raw and meatlike, the sleek curves of skulls and bony plates exposed. I saw where to draw the knife down the chest to make the Y that would reveal.”

Purpura’s capacity for demythologizing the common tropes of verboten spaces has found a new container in First Adventures in Beauty, though it’s possible that this newness only feels new as such to her reader. The seemingly slapdash appearance of the book’s pages makes clear that this is no ordinary book. Indeed, it was only after the first few pages that I settled in and started to understand how its excesses have something of a child’s sensibility. In 2013, several years before publishing First Adventures in Beauty, Purpura spoke at the New School’s Poet’s Forum. Snippets of her talk can be found posted to The New Schools YouTube channel where she describes an early writing project. “I kept very early on, at 13, 12, what I called a quote book. And I did this with two other friends. We collected everything we could. Song lyrics and poems and overheard conversations and sayings and headlines and movie titles and anything that was interesting in language.” It’s not so hard to imagine how these shared diaries in some ways resemble her most recent work. “So early on there was just this desire to collect language and to hold it and to make something with it. I collected little trinket-y things, I guess, the way a lot of kids do, but somehow those small objects seemed connected to language as well for me.”

In a passage midway through “Autopsy Report,” Purpura observes, “If looking, though, is a practice, a form of attention paid, which is, for many, the essence of prayer, it is the sole practice I had available to me as a child. By seeing I called to things, and in turn, things called me, applied me to their sight and we became each as treasure, startling to one another, and rare.” First Adventures in Beauty is a primer for the curious exploration of beauty and its many foils, a devotional in which Purpura reminds us that the substance we often seek when we regard that which strikes us as beautiful resides as much, if not more, in our own curiosity as it does in whatever object we’ve come to regard.

Caleb Curtiss’ poetry, essays, and book reviews have appeared in many journals including TriQuarterly, International Poetry Review, New England Review, The Rupture, The Southern Review, Passages North, Diode, and Ninth Letter. He is the author of A Taxonomy of the Space Between Us, which won the Black River Chapbook Competition.