Book of the World Courant

Second in a series of notes on writing, language, perception and power

V

In the museum, behind a transparent membrane of glass, lives an exquisitely-shaped porcelain dish. Manufactured by the Sèvres workshop for Marie Antoinette’s pleasure dairy at Chatêau de Rambouillet, the outer surface was illustrated with classical myths but purposely left ungilded. Honorably discharged after service in numerous hand-to-hand table engagements, the dish also survived the derisive judgment of a contemporary wag who thought it “barbaric in its simplicity,” and, of course, a revolution, and empire, a restoration and more.

Somewhere, behind the glass, invisible, the pleasure dairy itself unfolds – one of the many rustic simulacra built for an aristocracy eager for some respite, however fleeting, from the strictures of court protocol. In a manufactured arcadia such as this, or her Petit Hameau at Versailles, even the queen might imagine herself a carefree peasant girl, shaded from the Sun King’s implacable rays by a thatched roof overhung by ancient trees, her innocent nature finding perfect harmony in the timeless, immutable cycles of husbandry.

How then, in our era, to reground, even re-enchant, everyday life? Thomas Hennel, writing just after the end of WWII, called for a collective shift toward “the roots of production.”

The “reform of taste begins only in life,” he said. Hence “the world to-day has to live more dangerously, more realistically, than it has done for a century. At a moment when domestic life has greatly deteriorated, communal life becomes possible and organized: a common active need (though one of self-defense) replaces the axioms of waste leisure, and may go some way toward shaming the false and venal out of existence – (in art, music and literature).” Investments have become less substantial; work, especially in farm and field, has become again a common and wholesome means of livelihood: one which must quicken our sense of values.

The true master of his craft is one who has a comprehensive and at the same time simple idea of it... for in machinery as in the other arts harmony of the whole is much more important than elaboration of particular details...”

The hand may change the heart and the heart, the hand. The mind – what we call the mind – will come along for the ride. As will our political structures.

New York City, if it chose to, might become a genuine world trade center, or rather a center of world trade. The eponymous buildings are paradoxically named since both the original twin towers and the present complex buried what was once a site of actual trade under millions of square feet of office space utterly useless for anything besides metastasizing abstractions.

New York City, if it chose to, might reconstitute itself as a paradigm of social, even “spiritual” possibility. Not merely by “reindustrializing,” but by developing, out of its immense and famously varied pool of citizenry, a vital mix of new and ancient craft traditions – not least the arts of fire: glassmaking and pottery.

Such a shift in intentionality would open a mode of production distinct from the prevailing FIRE (Finance, Insurance and Real Estate) culture, and initiate a redirection of social energies toward meaningful locally-based employment, occupations, vocations and all that goes with the dignity of real work: mastery not of the economic lives of others, but of one’s own skills in relation to materials. This is the root of transformation, and heralds the moment when the question What do you do? turns, as though by its own accord, to What do you make?

And I forgot the element of chance introduced by circumstances, calm or haste, sun or cold, dawn or dusk, the taste of strawberries or abandonment, the half-understood message, the front page of newspapers, the voice on the telephone, the most anodyne conversation, the most anonymous man or woman, everything that speaks, makes noise, passes by, touches us lightly, meets us head on.

—Jacques Sojcher, La Démarche poétique. Steven Rendall, trans.

Did your thought evaporate in order that you realize its evaporative tendency, or did your cognition simply open to permit its evaporation?

A truth that only the object itself fully knew.

“Nearly” and “neatly.” Separated only by an “s.”

Given the physiological reality of the heart’s action deep within our bodies, it seems only natural that we should derive profound sensations from the act of opening and closing our hearts either to beings or to social artifacts and experiences – in short, from the exercise of love and hate. As in: “I love Sally’s teeth.” “I hate Cubism.” “Je kiffe Sexion d’Assaut.”

Modernity created the individual, but absolutely mistrusts her. Fears and loathes him to the point of castration. To the point of lobotomy.

A monstrous hybrid, worthy of any cabinet of curiosities (were he not so common): the corporate individual.

“You need to get on top of the individual people. Have a task list and check off that task list...”

So speaks a middle-aged new media boss cum guru to his twenty-something disciple over breakfast under the umbrellas outside Tarallucci e vino, a popular spot for Silicon Alley early birds to alight and warble their species of wisdom.

You are not listening really, but this monologue couched as conversation bleeds across the narrow space between tables. Boss Guru is upset, albeit new-agedly so, because Young Disciple’s team has failed to produce the requisite package of zeroes and ones demanded by a presumptive mini-app launch date.

YD begins a litany of excuses, implying vaguely that he’s not good at holding people’s feet to the fire, but BG interrupts: “See this as a leadership opportunity.” Which carries an unspoken, but tonally inferable or else.

YD mumbles agreement, or at least compliance and they rise to leave.

Heading east down 18th Street, BG’s still at it: “And that’s such an empowering thing...”

Sing, children: I said I wasn’t going to tell nobody, but I couldn’t keep it to myself!

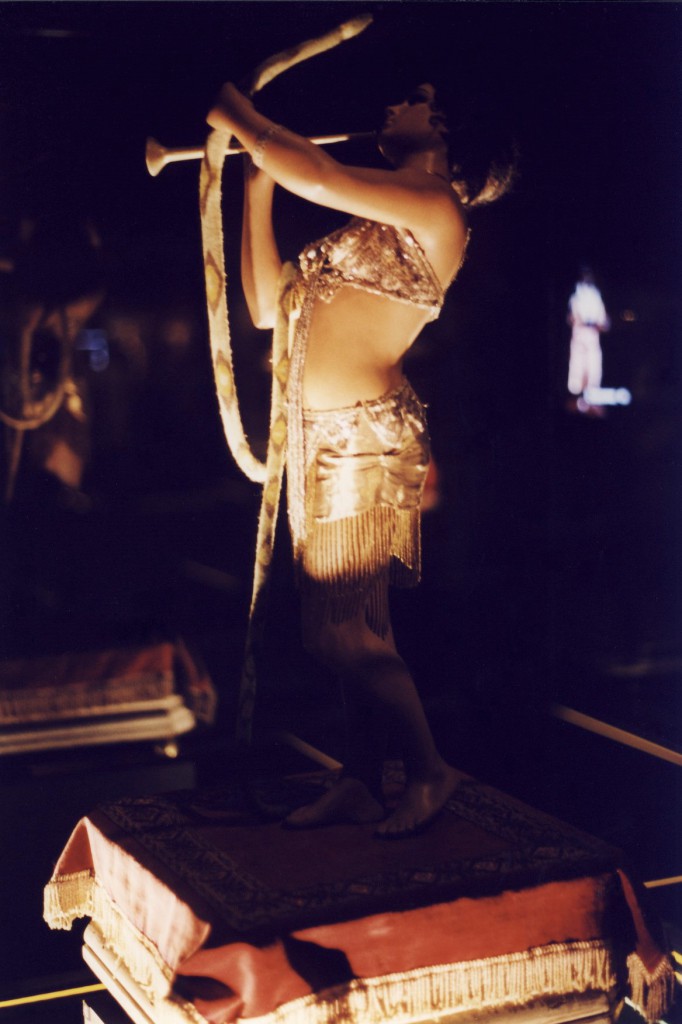

The sliding or oscillating between the poles of naturalia and artificialia constituted the pre-Enlightenment reciprocity of magic and erudition. The first, a living creature or organic form transmuted into an artifact (stuffed caribou). The latter, an artificial substance modeled on nature (Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog.) And then, in the long parade: centaur, unicorn, mermaid, and a thousand and one wonders.

And what of Jenny Haniver? A ray or skate mutilated to look like a wing’d sea creature with a human head. Described by Paré in the late sixteenth century, a variety of Jenny Hanivers were created to resemble angels, devils, dragons. It is speculated that the name originates in “Jeune (or Jeanne) de Antwerp” (called Anvers by the French) and subsequently “cockneyed” by English sailors. Linnaeus debunked one Jenny Haniver, the sensational Hydra of Hamburg. When the forgers threatened suit for slander, poor Carolus was forced to split town.

VI

Whoa! Manhattan!

Lead crystal: industrial transformation of common materials into the semblance of rock crystal.

Early summer morning in Washington Square and Maggie asks: “Did I ever tell you about the time I saw Bold One up on 135th Street?”

Between Maggie’s Aussie accent, white noise from the fountain and the first volleys of a New Orleans brass band opening up a jam, you draw a blank.

Who?

“Bold One,” she repeats, “James Bold One. I went out one morning and there he was, across the street with a film crew. He was pointing to my house – I guess he must have lived there...”

The band sallies full tilt into “Saints” and you have to lean in to hear her, but you can’t really – there’s far too many overtones resounding in your head.

No direction home.

“The hand of the craftsman is recognisable in the quality of life and the unity which develops under it.” Hennell.

There’s a pair of red-tailed hawks in Washington Square Park, Jimmy, and this spring, two fledglings. Someone tell Rufus and Vivaldo. Someone tell Beauford, Jack and Connie. It’s a sight to see.

The adult hawks like to perch on the wire cross of the Judson Church campanile and on the brass finials of the Silver Building flagpoles at the east side of the park.

Their aerie is way up in a window at the top of Bobst Library, you know, the big red sandstone fortress NYU built in the early ‘70s where 4th Street form a tee with West Broadway – which, btw, is now called LaGuardia Place. There’s even a statue of Fiorello himself just down the block, lifesize, in bronze, standing exactly across the street from the funky old building Jack moved into when he married Bea. Four, maybe five years before they had me. You’d remember the place: the Doctor Caligari staircase, orange linoleum floors, coal stove in the living room.

We were long gone by the time they built the library. Were you ever inside? It’s pretty incredible. The floors wrap around a truly vertiginous atrium. It’s said they paved the lobby with a weird stereogram pattern so students would think twice about jumping – looking down from above makes you a little nauseous – but occasionally a distraught kid leaps off the balconies anyway. No need to take a train all the way uptown, past Harlem – like Eugene did – like Rufus did – to Washington’s Bridge to find an abyss deep enough.

This morning, on the other side of the park they’re cleaning the arch: a crew of three atop a great articulating cherry picker, working on the motto facing south: Let us raise a standard to which the wise and honest can repair; the event is in the hands of God. One of the hawks – it’s big enough to be Bobbie, but it could be Rosie ¬– circling overhead. Another Country.

And the fountain’s on full blast: eight arcing water jets surrounding a central geyser. In go the children, wading, flopping, getting wet on purpose. A sudden windshift sends spray all the way to the perimeter and two Asian pretty girls in sun dresses jump up and flee. But then the breeze dies down and they return, resuming their seats at the edge. Like nothing ever happened.

If I were to get up now, and walk toward the Law School, would it slowly vanish, fake Federal brick by brick? Would the block rebuild itself – the Calypso Restaurant emerging out of the ground? And if it did, and I went inside, would I find you there? Writing orders, setting down plates – Crying Holy, word by word, rising inside your head?

—From Open Letter to James Baldwin

“The acquisition of Edenic wisdom (the ability to name and hence to know creation) through the magical memory theater of the curiosity cabinet represented nothing short of deposing Adam as the knowing subject; this in turn was a claim to the divinity of the individual. Painted upon the ceiling of the curiosity cabinet of Athanasius Kircher (the great Jesuit philologist) was the following inscription: ‘Whosoever perceives the chain that binds the world below to the world above will know the mysteries of nature and achieve miracles.’” Writes David L. Martin in Curious Visions of Modernity.

And had not Giordano Bruno – whose body was consumed by fire in the Campo de’ Fiori the year before Kircher was born – proposed that “it is by one and the same ladder that nature descends to the production of things and the intellect ascends to the knowledge of them”?

And you know that texts talk to one another. And do way more behind our backs than just talk.

Some time between tossing a silver dollar across the Delaware River and his exhorting the Constitutional Congress to raise a standard to which the wise and honest can repair, Lt. Col. George Washington commanded a militia that massacred perhaps a dozen – the numbers are imprecise – disarmed French troops, referred to in some accounts as a “diplomatic party.” What is not disputed is that the leader of the French, Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville – who lay wounded after the initial engagement – was brained, literally, by Washington’s ally, the Seneca “half king” Tanaghrisson.

“I heard the bullets whistle and, believe me, there is something charming in the sound,” said young Washington of the affair later known as the Battle of Jumonville Glen, opening skirmish of the French and Indian War.

Which had been preceded by numerous Tempestuous encounters, such as Columbus’s second voyage, wherein were catalogued the islands now called Jamaica – which he named Santiago (St. James) – as well as Guadalupe, Montserrat, Antigua, St. Martin, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. He also caused to be kidnapped at least one Caribe woman, who he “gave” to a childhood friend.

The crossing itself had been nightmarish for The Discoverer. Virtually sleepless for thirty-three days, he lost his memory and became so gravely ill that his crew feared for his life. But according to a contemporary account, things were no less vexed back in The Boot, where: in Apulia, at night, there were three suns in the middle of the sky but cloudy all about them and with horrible thunder and lightning; in the territory of Arezzo, and for many days infinite numbers of armed men on great horses passed through the air, with a terrible noise of trumpets and drums; in many places in Italy holy images and statues sweated openly; many monstrous men and other animals were born everywhere.

“People who shut their eyes to reality simply invite their own destruction, and anyone who insists on remaining in a state of innocence long after that innocence is dead turns himself into a monster.” Wrote Bold One in Notes of a Native Son.

VII

Naturalia / Artificialia

During the early Renaissance, ancient statues were believed to have been generated by the earth itself.

Headline above a photo of a leggy blonde in Diario de México: “Barbie Humana Busca Trabajo.”

For the Arabs, the chief value of the machine – particularly automata, in which the artificial emulated nature – lay in its capacity to produce delight. For the European North, the machine became a mania, at once a projection and sublimation of the impulse toward and away from God.

Over time, the play at creating “life” from mechanical movement turned to a deadly serious bid to escape Adam’s curse. Thus, the incommensurable drives to annihilate and “create” life emerged as the only available moves for a split culture which could no longer navigate the uncertain terrain between artifice and nature, could no longer sustain its internal dissociations.

Schüttlekasten: small boxes housing mechanical insects or reptiles which moved realistically when shaken.

The stones of the monastery re-locate, over centuries, to the walls of the manor house.

Impaled by Reason, the sign dies slowly and eventually begins to decay. At last, form itself dissolves and the sign, or rather its dust and ribbons, takes to the breeze.

Softitude.

We are made of the materials of our time. And something other.

And in that something other inheres the not-yet-material essence that animates form.

Because Americans cannot be intimate, we are informal.

Mi Kool-Aid es tu Kool-Aid.

The American problem was really never one of race per se. It was, rather, how to get rid of an overt aristocracy while preserving and advancing a system of authority based on class – or, more accurately, the mode of alienation produced and sustained by class relations. In the confused, dissociated, identity-free crab-basket that became the United States, a hallucinatory “whiteness,” established itself as the defining trait and generally-acknowledgd human standard.

Thus, when a jury found George Zimmerman not guilty of murdering Trayvon Martin, a reflexively-drawn analogy drawn between present-day race relations and the bad old days of Jim Crow leapt to the fore. Whatever its appeal, this analogy was misplaced and ultimately misleading since it served to divert attention from something much uglier and more frightening: the howling fact that, when placed on the scales of our repressed national discourse, a black life still weighs less than a white one. This need scarcely be argued since is demonstrable at so many levels including, but hardly limited to: access to miseducation, what passes for health care, a “fair” trial, incarcerability, and subsequently, a cell on death row.

The racial catastrophe known as the United States persists not so much in blatant or subtle forms of segregation as in directing a disproportionate amount of its internally projected violence, both active and passive, toward its black citizens, which it then justifies with the unthinkable, hence unspeakable, logic that it simply cannot afford to grant them full humanity. This psychosis is not remotely cancelled out by the presence in the Oval Office of an African-American chief executive. So it is hardly surprising that no discussion of the depths of our madness came up in the hyper-mediated public discussion of the case – we preferred to reify hoodies – since to acknowledge it would force to the surface a terrifying revelation: that this nation, this empire, was and remains a vast machine for degrading human life of all sorts at all levels while proclaiming itself the sole arbiter of freedom and justice in a world we have constructed as a mirror of our own fear.

Published by The Nation in November, 1947, a review of Gorky’s stories by James Baldwin, then aged 24, reads in part: “[Gorky] is concerned, not with the human as such, but with the human being as a symbol; and this attitude is basically sentimental, pitying, rather than clear, and therefore – in spite of the boast of realism – quite thoroughly unreal. There can be no catharsis in Gorky, in spite of the wealth of action and his considerable powers of observation; his people inspire pity and sometimes rage, but never love or terror. Finally we are divorced from them, we see them in relation to oppression but not in relation to ourselves.”

Tunneling for the Crossrail line near the Liverpool Street station in London, workers discover a Roman road and some human bones. It seems this was the site of a graveyard, buried by the modern city and estimated to contain as many as four thousand remains, including inmates of the Bethlehem Hospital, more familiarly know as Bedlam. One of the skeletons is likely that of Robert Lockyer, a soldier in the New Model Army, executed in 1649 for inciting the Bishopsgate Mutiny against Cromwell’s imposition of martial law. Accounts differ as to whether Lockyer was killed by hanging or firing squad, but contemporary descriptions of his funeral cortège are vivid and consistent. First came an advance guard of a thousand Levellers marching in files. Behind them, Lockyer’s bier draped in blood-dipped rosemary and surrounded by trumpeters. A company of troopers led his saddled horse, followed by “some thousands” of women and men, seagreen and black ribbons fixed upon their heads and breasts. Arriving at the graveyard, the procession was joined by “a numerous crowd of the inhabitants of London and Westminster.” Representatives of the Law, martial or otherwise, wisely absented themselves, as though, for the moment, authority existed in the body of the people, freely, and of its own accord.

In New York City, real estate is so powerful it bends light.