M. I. Devine’s essays have appeared in American Literature, Adaptation, Measure, and Los Angeles Review of Books. His writing has won support from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Cofounder of the pop music project Famous Letter Writer, he is an Associate Professor of English at SUNY Plattsburgh.

M. I. Devine’s essays have appeared in American Literature, Adaptation, Measure, and Los Angeles Review of Books. His writing has won support from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Cofounder of the pop music project Famous Letter Writer, he is an Associate Professor of English at SUNY Plattsburgh.

Kristina Marie Darling: Your essay collection, winner of the Gournay Prize in Creative Nonfiction, was recently released by Mad Creek Books, the trade imprint of Ohio State University Press. What are three things you’d like readers to know before they delve into the work itself?

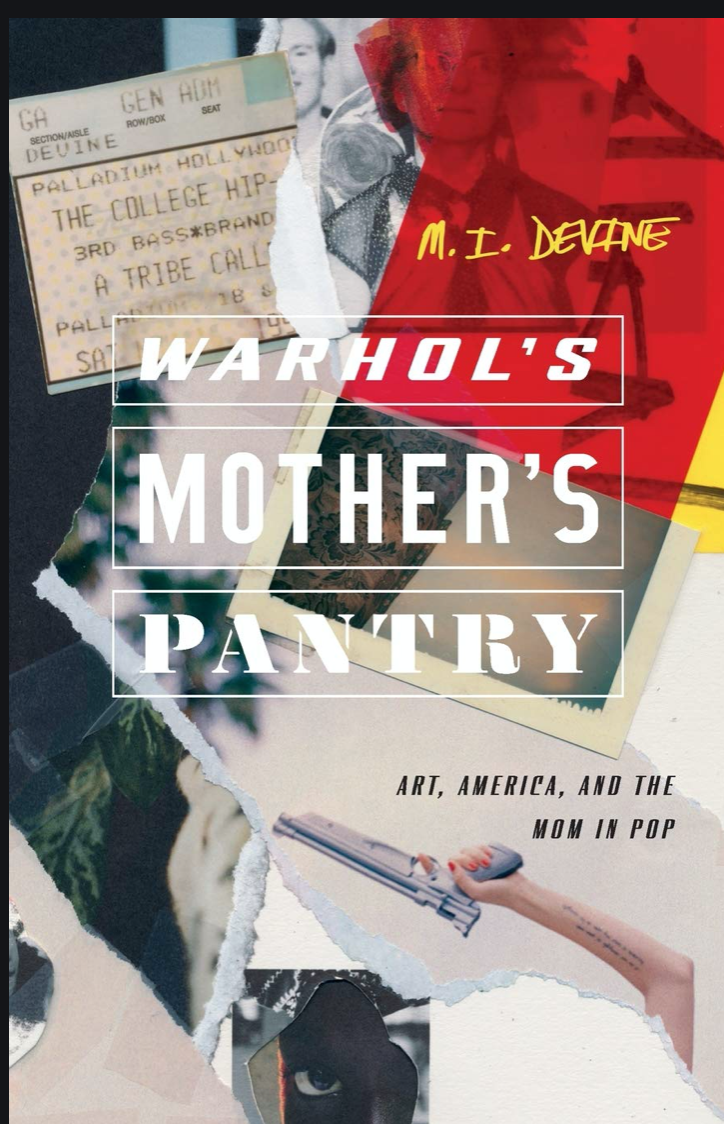

M.I. Devine: The first thing is simple: it both is and isn’t about Andy Warhol! In the same way, say, that his soup cans both are and aren’t about his mother, Julia Warhola. She was an immigrant, and a folk artist known for cutting soup cans into flowers. So, it’s about finding new depths. That pop is homage. That repetition is transformation. Things change by not changing at all (I always forget if that’s Pearl Jam or Heraclitus).

It’s a gamble. That pop is not what it seems; art is not what it seems; and maybe the essay form can be so playful, so loose and maybe so out there (mine rhyme, cut up pictures, footnotes are memoirs) as to come to terms with the absolute gravity of this fact.

Like Samuel Beckett, I want to “unknow better now.” Maybe Andy can show us how. The book tries—whether it’s on late Leonard Cohen or selfies by Gisèle Freund, Joyce’s Ulysses or Kendrick Lamar—and by trying says that the pantry is large and contains multitudes. O, yes, it’s also about Whitman!

But wait!—to use a pop phrase—There’s more! (Have you noticed we lost track?) It’s guided by the spirit of his mother who crossed closing borders in 1921. Yesterday is today. Now is then. High is low. It is about the eternal pop present that’s never not now.

OK, one more thing? It comes with its own soundtrack. I released a record called WARHOLA along with the book. So, you can read along. Get bored. Dream. Stream. Learn to sing by singing along.

KMD: Your essays utilize a very innovative approach to criticism, weaving together photography, poetry, archival material, cultural commentary, and artistic history. Why did this particular project necessitate hybridity and experimentation?

MID: Julia’s example, first of all. In Slovakia, they burn down her home. She sees everyone around her die. Does that put a rather new spin on DIY? Her response wasn’t a five chapter dissertation. It was to endure. That’s my muse, how she reuses and cuts through. That’s why I call her the mom in pop. She teaches Andy how to use scissors. Cutting is breaking and cutting is healing. And writing is, too. It’s a wound and it’s a suture.

And that’s why, to me, Andy is the eternal amateur, the screw up, getting it wrong, not figuring out even how to use his camera. God, what would we say to him today? Get your MFA!

Andy said, “I always notice flowers,” and I illustrate his mother’s journey with Campbell’s ads I discovered—from the early 1900s. They repeat and bloom. How else to communicate her journey? Her arrival? Her children? Perhaps I got it wrong, but when you “do something exactly wrong,” says Andy, “you always turn up something.” (Amitava Kumar has a great book, Every Day I Write the Book, about all of this. About allowing for strangeness in criticism. I think we need new models. We need to leave cracks in our writing. To let the life get in.)

KMD: Relatedly, in what ways are form and style politically charged?

MID: It would be easy to say that forms are stagnant and conservative and of course that would be totally false. What’s the epistolary memoir in Ta-Nehisi Coates’s hands? Outdated? Old-fashioned? Or a torch set aflame? Things change, radically, by not changing. And it’s precisely because the formal choice becomes an index of all we lost. Philip Larkin’s town is firebombed and he writes broken sonnets that turn to ash like houses on fire. Writing about the death of my friend, the Yale professor Sam See, I turn to childhood memories of looking through Duchamp’s peepholes in the Philadelphia Art Museum. I wrote it with Caroline Levine’s work on forms in mind. Someone writes that Duchamp’s door on his last installation is about reminding us that we can’t escape—our bodies. But that’s precisely wrong. The limits of poetry’s and pop’s forms teach us that we can share. “Burden” is another word for refrain, by the way. Forms allow burdens to be passed and carried by others. We know each other by our limits. That’s the beginning of solidarity.

In the book I briefly sketch a Black haiku tradition through the work of brian gilmore, a poet I admire; I workshopped with him when I was younger, along with Coates and others.

cold michigan streets

“black lives matter” sign

nearly covered with snow

Nothing changes. Forms can show that. And that’s how pop and art radically change us.

KMD: Tell us about the book trailer.

MID: O, wow, I guess it looks like Joseph Cornell made it! It’s DIY to the max (as one of my favorites, the late-great David Berman of the Silver Jews would put it).

What to say? On the one hand, it’s a video for one of the songs off of WARHOLA, our record released with my book. My partner, Ru, and I are Famous Letter Writer, a pop music project that launched a short film for each of the songs. I like to be as interdisciplinary as Andy. We co-created with a young filmmaker, Anthony Scalzo, in bringing to life artisanal pop. This song is called—ironically and not ironically—“All I Do Is Win,” and it’s about remixing the refrains we’re given. The pop material of life. Finding new meaning as we learn to find our voice. By singing along. In doing that we transform—and, not to give it away, but the book is about transformation, as I said before, and this is, too. Things are not what they seem. Soup cans are not soup cans. A dollhouse is not a dollhouse. Heck, as Duchamp taught us, even a toilet can be something else. (Spoiler alert! Wait for it!)

The less said, maybe the better?

KMD: In addition to your achievements in writing, you are also an accomplished musician. What can prose writers learn from musicians about artistry, storytelling, and the creation of narrative?

MID: Music is about measures obviously. The book opens with a scene where I am attending a Leonard Cohen tribute concert. It was the year after his death. The day after that concert I wrote the early songs for our record, and not long after a brief essay on Cohen. I think I was haunted, at the memorial in Montreal for Cohen, by how absolutely blindingly powerful his spoken words were. And he was dead! He reached the audience. That’s what all writing must do, aspire to. Refuse solitude. Share with others. Endure.

I wrote in that essay, “There’s a measure to things and that’s the things we like about songs. We remember how to sing by singing along.” I felt the form of Cohen’s words and I wanted to capture some of that in prose. If it works, at times, and I think it does, it works because there’s a startling innocence about it. And isn’t that what lyricism must often achieve? Limiting itself to the structure? Stripping itself of everything. Rhyme, you know, reminds first and foremost of our limits. Since then, I’ve played in festivals where I’ve had that same feeling, seeing the rapper Noname perform, among others, and I’m never not convinced that writing must aspire to what we love in music, what holds us there. Not just a formal economy, but I’m talking about a willingness to go there.

I performed recently with the terrific performance poet Edwin Torres and I thought the exact same thing. How to leap and not be afraid because the song—the form, the poem—will hold us. And our readers will learn to sing along.

KMD: What’s next? What can readers look forward to?

MID: Well, I maybe tipped my hand on the Cohen material, which I’ve explored in a more poetic, multi-genre manuscript. In criticism: I won a NEH for a larger inquiry into early cinema, poetry, and American culture, and I’m tempted to create out of that work an even more startling tapestry that samples visual history in new ways through a rather playful critical prose.

And we are going back to record in the studio soon as well. Famous Letter Writer very much depends upon the musical genius of my partner, and she is inspired recently by Laurie Anderson’s invocations in “O Superman.” I’ll follow her lead. And learn to leap.