Tom Henry is a recent graduate from Maryville University, where he majored in art and studied with mentors Scott Angus, professor of photography, John Baltrushunas, professor of design, and Dana Levin, professor of poetry. For more info see truthofmay.com

Dana Levin has this to say about Tom Henry: “Over many cups of coffee and roams together across campus, I’ve learned this: Tommy’s heart is open and his spirit irrepressible. It’s been amazing to witness how the confluence of digital technology and art has helped that heart and spirit express and impress.”

________________________________________________________

Cassandra J. Cleghorn: Thank you so much for agreeing to talk with me about your visual art, Tom. I want to start with a basic question. How did you come to make paintings? How old were you? What moved you to express yourself visually?

Tom Henry: Thank you so much for believing that my work is worth notice and that I’m worthy of an interview. You know, it’s funny, I had taken drawing throughout high school, and, before that, the standard art classes. But those classes were just for fun and easy A’s. I didn’t start painting until second semester, sophomore year of college, when I was 19. I have a degenerative form of muscular dystrophy, which makes my leg muscles ever weaker. At that point I was still walking (using a scooter for longer distances). One night, while in the bathroom, my legs buckled and I brutally hurt my hamstrings on both legs. This put me in a wheelchair permanently. I suddenly had so many emotions I needed to express. I exorcised myself of these emotions through painting — every negative feeling I was having I just loaded onto my brush and translated to canvas. Painting was the release I had been looking for my whole life, prompting me to change my major and devote myself to the craft.

CJC: Thank you for entrusting me with that very vivid moment in the history of your physical condition and your art. I gather these two aspects of yourself are bound together. I want to know more — if you feel you can say more — about how or why exactly painting was the medium that best allowed you to “exorcise” those emotions and negative feelings? How does painting work for you as “release”? How do you represent your body through your art?

And, practically speaking, I’d love to hear more about your craft — the brush, the paint, the canvas, as well as digital applications you may be using. There is such saturation of color and layering in your work. Can you talk about the time you spend on each image, how you return to it, what kind of attention (mental and physical) painting demands of you/produces in you?

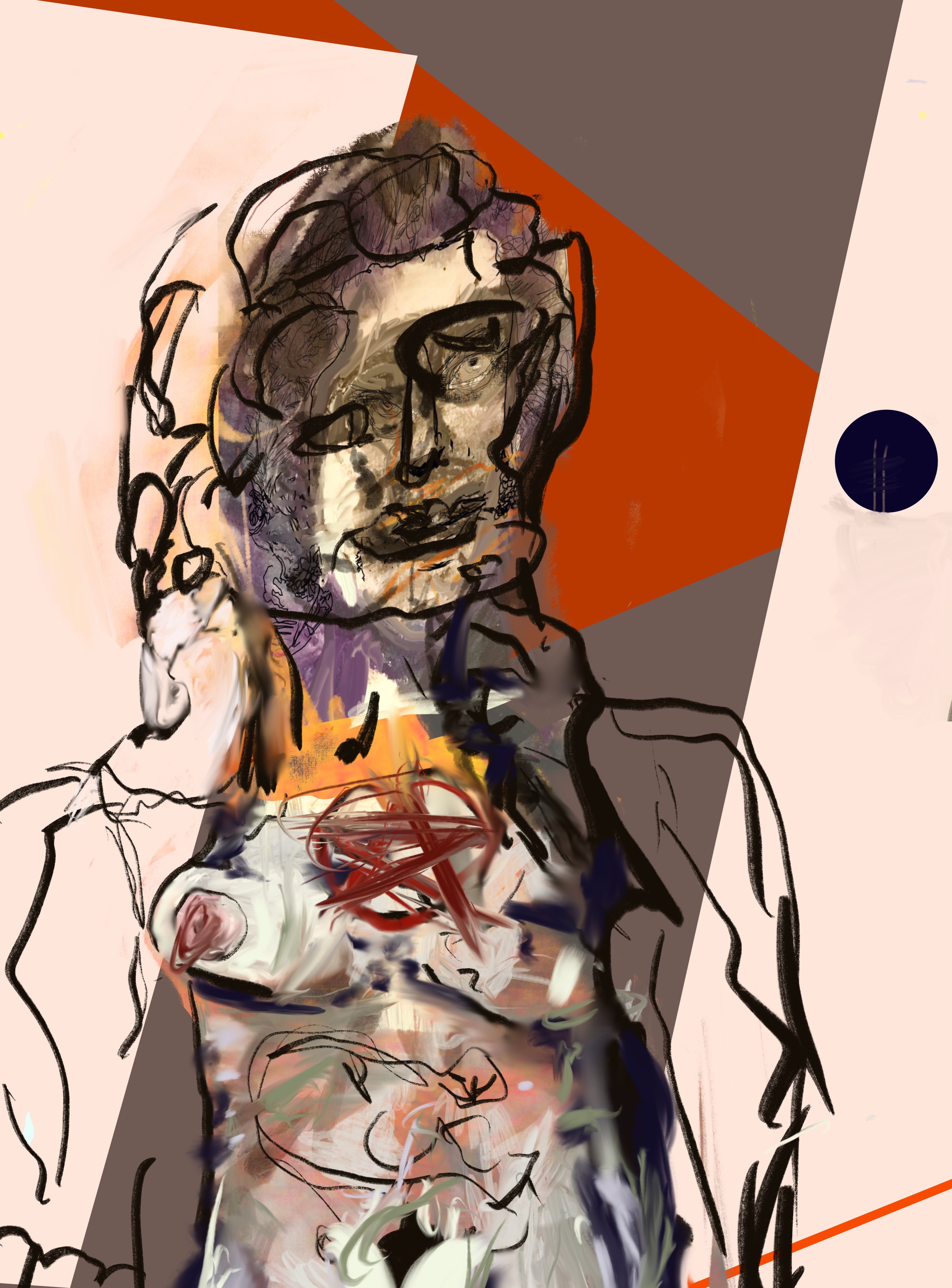

TH: Well, painting is a very taxing and at times painful activity for me. Although to be honest most activities are taxing and painful, for someone in my condition. Something about pushing through and overcoming the challenges involved with the physical action of painting helps me to create beautiful works. I have a tremor associated with my condition, which makes drawing straight lines and other fundamental techniques almost impossible.

Getting around these roadblocks helps to make my images original. I use anything I can get my hands on: oil paint, acrylic, water colors, turpentine, screen printing ink, marker, spackle, metals, canvas, paper, cardboard, clothing, wood, palette knife, pen, pencil, charcoal, pastels, and standard brushes from Michael’s. If I can do no more to the image physically, I’ll photograph it and use it as a digital layer to further work it on the iPad, where I have complete control.

CJC: What a complex mix of media! You sometimes write on your paintings as well. Can you say something about your use of language?

TH: Poetry is another release for me. The decision to write on a painting comes in the moment, it’s not something I plan out beforehand. I like to think of my works as visual poems.

CJC: The way you speak of your process, and the psychic and emotional intensity of your paintings, leads me to associate your work with expressionist painters. You’ve told me that among the artists most important to you are Francis Bacon, Max Beckmann, and Basquiat, which makes such sense to me. This brings me to something I’ve been wondering about since I first saw your work: how you represent your wheelchair, which you said earlier you think of as a “permanent” fact of your life. I’m thinking of the extreme horizontal painting (“Figure in Crisis”), in which the chair is above and to the right of the central figure, and facing the wall. The chair is rendered with great clarity and focus, as though it exists in a different emotional plane than the figure in the foreground, whose legs are bent as extremely as possible under their body. There’s enormous pain registered on the face of the figure, and in the gestures. I can’t quite read the relation of the figure to the chair, which seems as if it has been cast off, or is somehow beyond reach.

TH: I’m glad you brought up this painting. “Figure in Crisis” is my retelling of the day I fell back on my knees and basically permanently handicapped myself. The chair is rendered so that it occupies a futuristic plane of existence. That is, the fact of being in a wheelchair was always in my future because of the degenerative nature of my Friedreich’s Ataxia. That night, in one fell swoop, the chair became my present. So it came down to this: am I going to let this fact ruin my time, or am I going to at least attempt to embrace it? I’m trying to learn the necessity of being happy. I’m not going to let a wheelchair or anybody else stop me.

CJC: How exactly has the chair shaped your artistic vision. How has it served and/or impeded you?

TH: Well, last year I made two 10 x 10 foot paintings on drop cloths with enamel house paint, using the wheels of my chair to apply the paint —

CJC: Wow. How did that come about? How did it feel to paint with your chair?

TH: At first, I was using brushes, slowly dripping the paint onto the canvases that were stretched out on the floor. Eventually started to army crawl across the canvas, trying to limit how much paint I splashed on my chair. Finally I said “f*ck it” and used the wheels of my chair to finish the painting. From the moment I made that decision, I felt...somewhat unstoppable. It was liberating. Using the chair to my advantage, and having the liberty to choose to paint with it was beyond empowering to me. I felt immortal.

CJC: The physicality of this process! Painting meets dance meets performance art. I think of artist Sue Austin, who is also wheelchair-bound and who has worked with engineers to develop a special chair that allows her to scuba dive. Here’s the video she made, and the talk in which she describes her relation to her chair. And I think of the dancer, Gregg Mozgala, who has cerebral palsy. Have you seen the film, “Enter the Faun,” about Gregg’s work, made by the choreographer Tamar Rosoff and the filmmaker Daisy Wright?

Your paintings similarly explode my preconceptions. I used to think of the wheelchair as a clumsy tool, a necessary, but awkward way some people have to get around. But you (and Austin and Mozgala) have transformed my ideas about art and accessibility, about the fiction of limits, and ways of extending and remaking techniques, genres, traditions.

I want to think more about the question of the “unevenness” of an artist’s work. It’s a word that comes up often in editors’ conversations, often about poetry (which I deal with more than visual art), but in respect to any kind of artistic work. “Unevenness” seems like a potentially problematic category of judgment when considering work made by differently abled artistis. Can you say more about the tension between the necessary constraints an artist may experience and the creative opportunism such constraints make possible?

TH: I’m incapable of making perfect things due to my lack of motor skills, my tremor, etc. Any “unevenness” of execution (apart from questions of design and composition) is due to my muscular dystrophy, which affects my hands and which will eventually strip me of everything but my mind. Certain physical limits are an inherent part of my existence. I’ve embraced this fact and adopted it as a part of my style. Unevenness in application is something I genuinely consider to be my personal style, an intentional effect.

Physically I’m ever weakening, if gradually. I’m extremely fatigued often, though I can push through the weakness when I need to. Heart disease comes with my condition, as well. A couple of years ago I had two occurances of a fibrillation, where my heart reached 270 bpm, and I was diagnosed officially with heart failure. I have technically died twice. I saw the cardiologist last week and he gave me an estimate of upwards of fifty percent chance to survive the next five years. If I don’t die first, I’ll eventually become deaf and blind, unless a cure for Friedrich’s Ataxia is discovered. But even a cure might be too late, because I already have heart failure. So that’s where I am emotionally.

Mentally I just know I won’t be able to live with myself if my artwork isn’t appreciated as it should be. My works are really my children. They will live beyond my lifetime, so I want to make sure they thrive!

CJC: Again, Tom, thank you for your honesty. I am humbled and inspired by your strength and vision. I hope you know that this interview — and, more importantly, your images themselves — will have a life beyond what we can imagine. That’s the wonder of the internet, and of journals such as Tupelo Quarterly. Your art and your ideas will continue to be shared, finding audiences in surprising places. (Think of how I first “met” you, after seeing your images shared by Dana Levin on Facebook after your senior art show.)

I want to thank you for digging so deeply into your artistic process and for trusting me and the readers of TQ. Pain and fear and joy and the will to experiment are tied together powerfully in your paintings. I hope you will stay in touch as you continue to make art beyond even your own wildest imaginings.