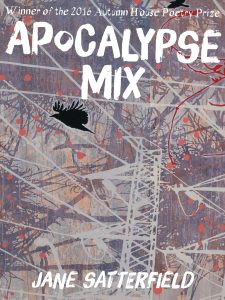

Jane Satterfield’s Apocalypse Mix is a time capsule of the pre-Trump global political landscape that documents the ways in which the military-industrial complex has been normalized and stitched into the fabric of our lives. These poems trace the commodification of both war and its opposition, from the “renewable fashion for military chic” (8) to the inversion/perversion of punk anthems to department store Muzak, but they also examine how we sustain ourselves in the face of loss and conflict.

Jane Satterfield’s Apocalypse Mix is a time capsule of the pre-Trump global political landscape that documents the ways in which the military-industrial complex has been normalized and stitched into the fabric of our lives. These poems trace the commodification of both war and its opposition, from the “renewable fashion for military chic” (8) to the inversion/perversion of punk anthems to department store Muzak, but they also examine how we sustain ourselves in the face of loss and conflict.

The collection bristles with echoes of war-torn and protest verse, as numerous epigraphs from poets and songwriters frame each section with lyrics and lines against violence/war or in memory of those/all lost. Most striking is the first epigraph of the first section from The Clash’s “Hate and War”: “You have to deal with it” (1). Satterfield’s Apocalypse Mix witnesses the ways those on the front lines and those at home sustain themselves–sometimes through direct engagement, often through avoidance.

Song and music are vital in the collection, as the speaker is transported to the moment where she first or last heard a song and who she was in that moment. Apocalypse Mix opens with “Radio Clash,” where the speaker asks, “And was I what I played?” (3), reaching back to the first moments of the speaker’s consciousness or to the end of her innocence. There’s a hint of nostalgic optimism with the Clash’s “power chords striking again and again, a sound/like sun burning through fog, like the sheer belief/anyone might blossom beyond some epic fail” (4).

Many of the poems employ Satterfield’s signature descriptive-meditative structure, where the speaker is struck by something in her environment, moves to an interior moment (memory/history/aside), and re-engages with the original scene with a changed or expanded perspective.

A powerful example of this strategy is in “Elegy with Trench Art and Asana,” where the speaker starts with a description of the yoga class she’s attending above a bowling alley and moves into a mediation on her inability to stay in the “here, now” as the “summer/camp duckpin party” below triggers memories of the Great War Exhibit she recently visited. The “trench art” itself is the first of many references in the collection to post-war kitsch made marketable and how this commodification–though a means of literal and metaphorical survival practice for many–has been exploited. The poem then imitates its own structure: “In Shavasana, we seek sensory/withdrawal, an entry into deeper meditative states. After,/ we must rise again to collect our things...walk back/into our separate worlds” (9). Returning to the living, the speaker tries “not to flinch at the giant screen TV/with its flashing, disastrous crawl” as the day’s ticker-tape of news and tragedy has increased gravity.

Satterfield’s descriptive-meditation continues in “Triptych,” as the speaker moves between past and present, inhabiting first a memory with her infant/toddler daughter and an encounter with a stranger in hijab. The speaker asks, “In this time before fear was everywhere,/what was the reason she caught my gaze?” (10). The second section of the poem moves to the present where the speaker is watching the riots and crowds in London protesting immigrants and Muslims; here, the speaker asks, “How to speak/of what we share, what separates us?” (11). The poem returns to a description of the past and the stranger touching the child’s face, saying, “beautiful” and “blessed” (11).

This juxtaposition of personal story and larger cultural moments or history engenders a poetry of witness, as Carolyn Forché defined it: poems that exists in the “social,” “the space between the state and the supposedly safe havens of the personal” (Forché, 17).

The witnessing continues in “Special Screening,” a poem revisiting the screening of the film Black Hawk Down and crisis itself. The speaker offers, “Here’s/a window into war, a fast daylight raid/gone wrong” (13). Though the film offers outsiders a view of the conflict and tragedy, it is not free from the commodification the book explores, as the speaker reveals: “The varied means (and the charge this film was one)/of manufacturing consent” (13). As the poem draws to close, it returns to the present moment, to the weather in Baltimore, “a clipper bringing heavy/snow”: “We brace ourselves against the coming//storm, the fate of those who fight, those trained/to make a difference” (14). Again, speaker and reader emerge with a different world view and the multiple storms on the horizon.

Satterfield avoids slipping into rhetorical rants, as she reflects on commodification, through her use of the descriptive-mediation structure, as demonstrated in “On Not Buying Vintage Oil T-Shirts at Old Navy” where she artfully moves the reader through the landscape of “Apocalypse and empire” (16) and later in the book in “Object Lessons,” where everything from board games to ice cream choices reflects the normalized and commercialized military industrial complex: “Atomic Fireballs, bomb-/pops frosted red, white, and blue” (51).

What is most impressive about this collection is the speaker’s admitted complicity. Though she doesn’t splurge on the t-shirts in the prior mentioned poem, in “Salt”—after riffing on mythology and origin, family relatives, and a photograph that “reminds us of its mythic heritage” (18)—the speaker returns to the present: shopping for salt to make a sweet, something decadent—something to make suffering and loss palatable. This is the other side of commodification, where physical artifacts and comforts sustain the living on the battlefield and the sidelines.

This idea is gorgeously rendered in “Parachute Wedding Dress,” a poem that appears in the third section of Apocalypse Mix. In “that world of rationed goods” (38), the dresses turned parachutes (or reverse) invoke a tenderness of trying to salvage the everyday in war, whether through donating a dress in hopes of providing a lifeline from the sky or salvaging a bit of silk to fulfill a beloved’s “dream of a white/wedding dress” (37). The poem, and the collection as a whole, recounts the “economy and love/handed on and handed down/its life and afterlife” (38).

Similarly, in “Combat-Ready Balm” the speaker reflects on the ways in which those at home prepare themselves and their beloveds to engage in war: “Just like me to offer/an apocryphal saint as protection, a saint whose feast day/was dropped from Church record in the absence of any/historical evidence he’d ever existed...[D]oes it matter if Christopher’s simply a stand-in/for the soul treading turbulent waters?” (48). Like many of us, the speaker would pay any price and invoke all manner of ritual and faith to protect the beloved.

The second and fourth sections of Apocalypse Mix engage in the same themes as the rest of the collection, but they offer different formal explorations. The second section is comprised of “Bestiary for a Centenary,” a series of stripped down elegies for animals–pigeons, camels, dogs, horses–sacrificed in the service of war. By witnessing the suffering of these innocents, the narrator concludes, “We have no name/for the scale of pain” (34).

The fourth section “Migrant Universe” is a series of ekphrastic prose poems responding to Tanja Softić’s work, where flame is both “[i]njurious and purifying” (57). These poems continue the theme of the here and now rubbing up against a history of violence and loss. Like Softić’s artist statement, Apocalypse Mix enacts the impossibility of an objective recollection and seeks to unpack how memory transforms and alters experience.

In the final section of the book, the poet turns her attention to domestic warfare in the United States, particularly the country’s long history of racism and inequality. In “Elegy with Civil War Shadowbox” she returns to the descriptive-meditative structure, opening with the speaker’s new routine after September 11, 2001, and moving to the question of “how to pay tribute to what/is simply beyond words” (68). As the speaker considers the Antietam National Cemetery Memorial Shadowbox, she acknowledges how “one man’s memento/of hope and healing...left out conflicts still simmering–segregation’s/mark in the veteran burials from the world wars” (69). Though this poem echoes the previously discussed theme of souvenirs of war, it reminds the reader of the limited, and at times racially biased, perspective of these artifacts.

Another poem that explores the speaker’s historical complicity is “Crossing Shenandoah in Late Summer.” This poem starts in the past, remembering the family’s move to Jefferson and the childhood memory of “our thriving divisions,” including “gun rack[s]/draped in the Stars & Bars” and “hooded marchers’ rallies” in the next town where a “Klan Grand Dragon lived” (70). This memory is juxtaposed with the speaker uncovering the news of the mass shooting at the Charleston A.M.E., and she returns to the previous memory, asking: “If we had stopped on that summer day/& I’d have dared to ask that driver why he flew the Confederate/flag, what would he have said in defense?/Pride & heritage, liberty? I’m still staring at that open secret.” This self-indictment asks the reader to examine their own complicity on the “still simmering” racial conflict in the States.

Apocalypse Mix is masterful and timely collection, urging the reader, and aspiring poets-of-witness, to examine one’s daily connection and larger history with resistance and struggle. Jane Satterfield’s poems do not ask us to engage with conflict and war from a distance; they smartly invite us in through our common landscape and routine and ask us to consider where we stand.

Citations:

Carolyn Forché, “Twentieth Century Poetry of Witness,” American Poetry Review 22:2 (March-April

1993), 17.

Marks, Corey, “The Descriptive-Meditative Structure,” Structure and Surprise: Engaging Poetic Turns.

New York: Teachers and Writers Collaborative, 2007.

Emari DiGiorgio is the author of Girl Torpedo, the winner of the 2017 Numinous Orison, Luminous Origin Literary Award, and The Things a Body Might Become. She’s the recipient of the Auburn Witness Poetry Prize, the Ellen La Forge Memorial Poetry Prize, the Elinor Benedict Poetry Prize, RHINO’s Founder’s Prize, and a poetry fellowship from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts. She’s received residencies from the Vermont Studio Center, Sundress Academy of the Arts, and Rivendell Writers’ Colony. She teaches at Stockton University, is a Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation Poet, is the Senior Reviews Editor for Tupelo Quarterly, and hosts World Above, a monthly reading series in Atlantic City, NJ.