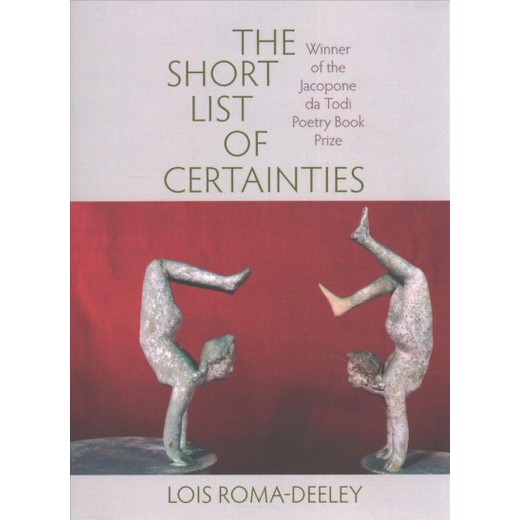

If poetry makes inwardness palpable, Lois Roma-Deeley’s poetry collection, The Short List of Certainties makes belief and resilience in the face of the void attainable. In this collection housed in a trinity of three parts, poet Roma-Deeley looks into the great mystery and embraces the flux of the universe as her poems pendulum between pain and hope and uncertainty and certainty.

If poetry makes inwardness palpable, Lois Roma-Deeley’s poetry collection, The Short List of Certainties makes belief and resilience in the face of the void attainable. In this collection housed in a trinity of three parts, poet Roma-Deeley looks into the great mystery and embraces the flux of the universe as her poems pendulum between pain and hope and uncertainty and certainty.

Poems in Part I, fronted by St. Augustine and Pascal epigraphs on hope, courage and wagering, traverse themes of disaster, change, nothingness and ghosts, pointing to the human need for spiritual awareness that often begins in the mirror of nature. In Part II, poems suggest themes of transitions, turning points, and re-creation akin to St. Paul’s reawakening on the way to Damascus. Part III continues the trajectory in recognizing a divine presence from within, through poems infused with praise, elegy, dreams, and transcendence, culminating in the poem, “The Short List of Certainties.”

In Part I, poems challenge one’s beliefs and sense of place in the world, allowing readers glimpses at how nature, displacement, and anger affect belief as seen in:

“Nearby Is the Country”

The past moves inside me

as water from a swollen river makes its inevitable way

to the sea.

And I don’t know how to name this place

where, standing on the rooftop of a flooded house,

the bloody blind one, shouts and then,

looking up at the sky,

waves and waves and waves.

The speaker’s inability to name this place gives it its “anywhereness,” leaving readers on uncertain footing, one of humankind’s greatest agitators for the desire for certainty and something to hold on to.

Some poems even make playful use of textural effects such as strikeouts, which in the following excerpt draw attention to deliberate, taunting near-erasure, creating a sense of urgency in the flotsam and jetsam of life’s disembodied and discarded items, and what they suggest about the humans that collected them, or the lives those abandoned items and their effluvia and impending demise represent.

“A Banjo Strums Itself to Sleep”

Here is a map of the world smelling of ground coffee and baking soda.

This was a house with 36 dead cats.

Here are stacks of the New York times, the canyon maze

winding through the hallway and bedroom and living room.

There was a Winterest chandelier swinging from the ceiling...

The poem ends with the speaker placing a pearl between the teeth and biting down, suggesting the hard wisdom acquired in measuring a life.

In Part II, grounded by themes of turning points and transitions and girded by poetics, Roma-Deeley gives readers mental leaps that re-create a desire for belief that something will change and that belief in belief may be the ultimate means toward deliverance. Thus, “When Nothing Is Right,” charts the uneasy sensations of a unsatisfactory day:

Make an egg white omelet.

Throw it out.

Eat a chocolate bar.

Take a long shower. Use all the water while singing

into a bar of soap: ‘There’s No Way Out of Here.’

Hyperventilate about global warming.

. . . . . . . . .

Walk back into the house, slamming the door shut

until the glass rattles and almost breaks.

These actions, juxtaposed with spoken and unspoken tensions, agitate readers to contemplate how they process time and consider its constructs and their ability to be present to uneasiness, even in the absence of purpose or reasons for uneasiness: “Count / the minutes on the clock, the change in the glass bowl, the number / of times my sister asks: What do you do all day?”

In concluding Part II, “The Dark Night Speaks to the Soul,” brings taut the urgency of the human condition:

Your prayers begin and end unanswered

as echoes in a whirlwind. You’re shattered.

A tornado of fear has ripped away

your insight.

The poem then delivers images pointing to the desperate human need for transcendence versus submission to ennui: “Yet, like a madman with a bouquet / of tin cans, you’ll rattle against the balustrades . . . ”.

Ultimately, Lois Roma-Deeley’s The Short List of Certainties takes readers on a spiritual journey through the three stages of belief that plant seeds in the unconscious for epiphanies that reverberate long after you put the book away. In such, the capstone title poem contains an evocation of the scant but tangible stepping-stones of certainty on which humans can rely for the journey.

“The Short List of Certainties”

Let us remember the taste of salt on the tongue. The way snakes

move through the open reaches of Iron Mountain. Can’t you

picture the young mother standing in the doorway (hopeful) of a house

made sad by too much sadness, not enough work? And when

you are offered the smell of creosote after a rain, the whir of

strange voices on this city street, a pearl moon—do not calcu-

late the cost. Let us last—or at least—bless the empty desert

as if it were a blank page. Then, having courage, let us write a

word or phrase on the short list of certainties something that

sounds very much like praise.

In this poem allusions and symbols play against each other launching ancient resonances, with salt, for example, symbolizing the covenant of partaking in life’s perpetual obligations. Likewise, snakes have for all time symbolized evil, yet the poet places them on Iron Mountain in contemporary Arizona, thus alluding that it doesn’t matter where snakes show up – in ancient or current landscapes, evil is forever part of the great mystery and how we consider its contexts. The presence of mothers and doors suggests the ongoing nature life’s origins and passages, from daily-commonplace to the mystery of death, in which sadness will always play a role. Regarding the blessing of the empty desert as a blank page and a listing of certainties as praise, these summon readers to orient themselves toward the beauty and mystery of the human experience and that we have some choice of how we color the empty canvas of days ahead.

To consider the idea of “certainty” in both Lois Roma-Deeley’s signature poem and collection, The Short List of Certainties, suggests that belief for humans, serves the “certainty of uncertainty,” insomuch that belief gives us hope in that which we cannot see; that in the face of senseless shootings, the atrocities of concentration camps and Boko Haram and ultimately the void, the greatest free choice we’re called to make is our attitude when faced with such. In this sense, this spiritually-oriented poetry collection calls readers to consider how to make sense of our world and grapple with the mystery of mysteries beyond us.

As a poetry collection, Lois Roma-Deeley’s The Short List of Certainties fires-off the faith muscles—that arise from street and spiritual encounters—readers may not even know they possess. Deeley’s sideways exploration of courage, paying attention in the world, universal vulnerability and glancing faith, resound with the music of Merton’s reflections on Gregorian chant: “...full of variety infinitely rich because it is subtle and spiritual and deep, and lies rooted far beyond the shallow level of virtuosity and ‘technique,’ even in the abysses of the spirit, and of the human soul.”

Renee G. Rivers holds an M.A. in English from SUNY Brockport and B.A. in German via the Goethe-Institut-Muenchen and teaches Writing at Arizona State University at the West Campus.

Her stories have appeared in: PBS Filmmaker Jillian Robinson’s Change Your Life Through Travel, Canyon Voices, and The Feminist Wire and have won international awards from SouthWest Writers and Tin House.

Rivers currently writes about teaching in remote Alaskan villages and taking her father in a wheelchair to Mount Everest and how their understanding of themselves as seekers propels them into adventures that find them exploring their own inner geography and other places at the edge of the map.