Featuring new work by Amy Sherald, Hayv Kahraman, Abeer Hoque, Jeremy Dennis, and Rachel Eliza Griffiths.

In place of our three-artist-portfolio format, in this issue of Tupelo Quarterly we take a look back to the work of five artists we have previously featured to see what they are working on now. In keeping with the theme of this special summer issue, I’ve taken this opportunity to highlight new work by painters and photographers of color with current or recent exhibitions and/or new publications. Here, as with every issue, we feature both established and emerging artists. -Elaine Sexton

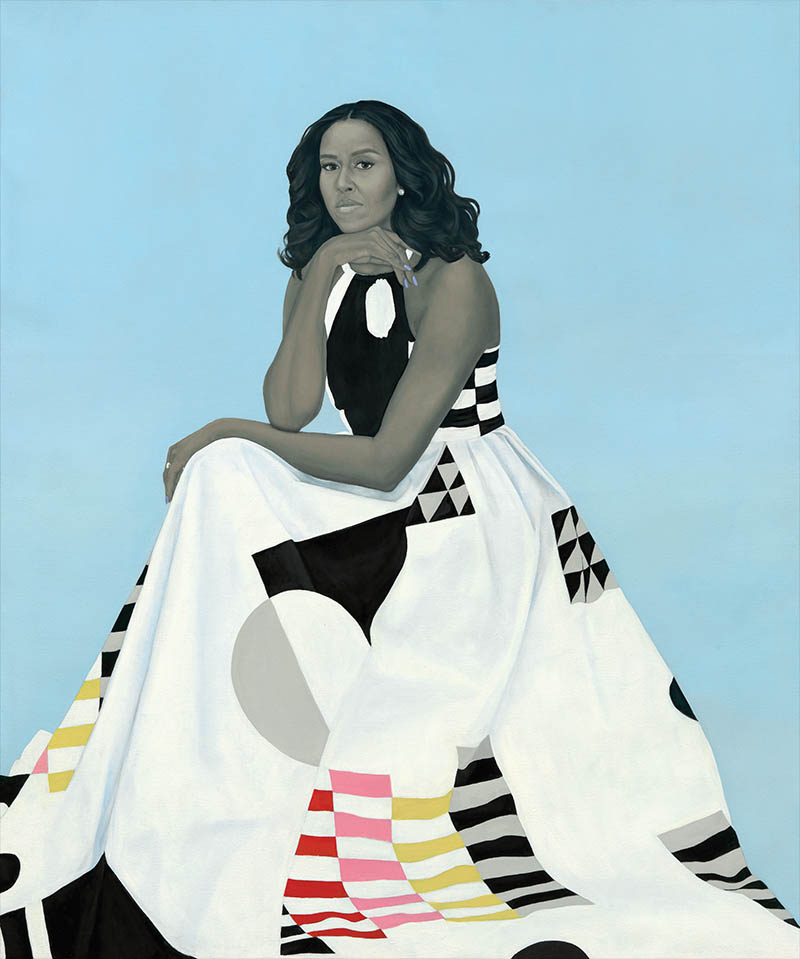

Painter Amy Sherald’s work drew national and international attention and acclaim after Michelle Obama chose her to paint her official portrait now hanging in the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

In my 2016 micro-interview with Sherald, the Baltimore-based artist talked about finding the people she paints from her everyday life, and costuming them. Working in a signature color palette, choosing to not distinguish one skin tone from another, the skin color of all the people she paints is the same, all are equal, all the same cool grey.

Two years after the unveiling of Michelle Obama’s portrait, Sherald was commissioned to paint a posthumous portrait of Breonna Taylor, featured on the cover of Vanity Fair (Sept. ‘20), after her brutal killing by plainclothes police in Lexington, KY. Nearly a year later, copies of this issue are still on display on some newsstands like Casi Magazines in the West Village, NYC.

“The Great American Fact” is the most recent of several exhibitions of Amy Sherald’s work at Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles and New York. The title of this show is drawn from text by Anna Julia Cooper (1858 –1964), an American author, born into slavery, educated at the Sorbonne, who went on to become a prominent African-American scholar. Sherald quotes Cooper from her 1892 her book, A Voice From the South by a Black Woman of the South, stating that Black people are ‘‘the great American fact.” Sherald links this to her work in portraiture, saying her paintings are “a resting place for people to see a reflection of themselves that is not in resistance or contention, just a Black person being a person.”

Here is “Amy Sherald: In the Studio,” a video produced by Hauser & Wirth, where the artist puts the work from this 2021 exhibition in context:

Note: To see more of this and the other artists in this feature, scroll to the end for a link to their galleries, and original interviews with Tupelo Quarterly.

Hayv Kahraman, born in Bagdad, Iraq, lives and works in Los Angeles. Since first appearing in Tupelo Quarterly in 2015, her elegant, curious, sometimes humorous social commentary has become stranger–– more explicit, symbolic. All are self-portraits, infused with symbols, observations of what she calls “the brown body indoctrinated into whiteness.” From “Anti/Body,” this painting (and detail) is “Defibrillator” from an early summer (2021) group exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery (New York):

Left: Hayv Kahraman, Defibrillator, 2021, oil on linen. Detail: Boobs.

Right: Hayv Kahraman, Defibrillator, 2021, oil on linen.

© Hayv Kahraman. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Commenting on Kahraman’s work, Jasmine Wahi, the Holly Block Social Justice Curator, Bronx Museum, suggests the artist focusses on “the way the femme body exists in a state of ‘unsafety’ in the world, ultimately opening a broader dialogue around women’s bodies in states of war. Using the geopolitical implications of the pandemic, she explores larger issues of xenophobia, political dominance, and dangerous global ideologies. Kahraman pivots the discourse of epidemiologists, drawing a parallel to the language of state-sanctioned propaganda by creating layers of coded meaning and multiple entendres within the realm of her own individual history.”

Hayv Kahraman, Chameleon, 2021, oil on linen.

© Hayv Kahraman. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

In an earlier solo exhibition this spring, “The touch of Otherness” at Vielmetter (Los Angeles), the pandemic, immigration, again, the “vocabularies” of war and of immunology, epidemiology, and contamination are issues Kahraman talks about in describing this body of work in this gallery’s video. [scroll down to the video on this site]

Here is the artist talking about her work pre-pandemic, in an Art Dubai interview, setting the stage for the work of “the body, her figure,” and “thinking outside the box” in her Los Angeles studio:

Abeer Hogue, a Nigerian-born, Bangladeshi-American photographer, poet, and editor, featured in an early issue of this journal, is also an intrepid traveler. Even now. When I reached out to her earlier this summer, she texted me back from a stalled plane on the tarmac about to take off.

On the subject of her ongoing project “Passages”: “I’ve never had an easy time parsing borders,” Hoque says, “even the places I belong to, and there are many, I sometimes feel alien, and some strange places have become home. This is one of the reasons I love photography. It doesn’t matter where you’re from, only who you are and how you see it. It lives beyond language, maybe even beyond place. Passages are among my many photographic obsessions. They feel like a way home, lonely, beautiful, promising.”

All of these images pre-date the pandemic, but are part of a growing body of work. As the possibility of travel opens up, the same images, taken less than two years ago, take us back to a time when this risk of contagion was not the first thing to consider when jetting off to other countries, continents, or even another state.

Left: Night ride on the Williamsburg Bridge, NYC; Center: Window to the Great Wall, Beijing; Right: The path to the water tower, Kolkata.

To experience the breadth of Hoque’s “passages” from Argentina, Jordan, Ireland, China, to India, Nigeria, and the United States. Click here to see more on Flickr.

Abeer Hoque is the recipient of a New Works grant from the Queens Council on the Arts to complete another project, a chapbook collection of what she calls photo poems. Tune in to a future issue for more on this work.

Artist Jeremy Dennis, a tribal member of the Shinnecock Indian Nation in Southampton, NY, exhibited work from an ongoing series, “Rise” (2018-present), which reflects upon “the inherent fear that one day – oppressed groups may rise and defend themselves.” These installation shots are from the Leiber Collection in East Hampton, N.Y., on the east end of Long Island. They were exhibited earlier this summer, in an outdoor space not far from where the artist currently lives.

Dennis describes this work nailed to trees in this outdoor exhibition: “As an indigenous tribal member who has observed the aftermath of colonization and followed my curiosity in the story of survival, especially as a Federally Recognize tribe east of the Mississippi, ‘Rise’ approaches the concept of a future Native American uprising from a complicated perspective of military and land deed neutrality, cultural assimilation, and as a people hiding in plain sight. With the rise of the zombie motif in popular culture, the zombie may be interpreted as the great celebratory enemy, replacing the American Indian. Thus, ‘Rise’ appropriates the aesthetic and concept of the zombie apocalypse by replacing the gory zombie figure with the American Indian, whose simple presence causes terror.”

Late last year TQ featured a portfolio of Dennis’s stylized still photographs, portraits of Native American women looking like Hollywood stars, a commentary meant to redirect the viewer’s attention to the ongoing desecration of the artist’s ancestors. You’ll find a link to our micro-interview and this work below.

Rachel Eliza Griffith’s fifth book, Seeing the Body, a collection of poetry with photographs, came out in 2020, in the midst of the pandemic. She joined a world of artists and writers, galleries and bookstores, suppliers and publishers, like everyone, who had to re-invent their practices and work lives to survive sheltering in place. A nominee for the 2021 NAACP Image Award in Poetry, Griffith’s photographs, too, have long been integral to her thinking and making, something this makes book makes clear.

When I interviewed Griffith in 2017, her photographs, portraits of poets from Ross Gay to Lucille Clifton, filled the walls of Poets House in Lower Manhattan (still temporarily closed due to the challenges of the ongoing pandemic). Griffith described “American Stanzas,” as a project that “explores my questions and challenges where identity and representation, particularly of black bodies and black imagination, are in play with one another.” A double self-portrait, an homage to Frida Kahlo’s “The Two Fridas (1939)” from this exhibition is included in this new collection under a section of the book entitled “daughter: lyric: landscape” which Griffith describes to serve “as a map of the self and of the greater world in which I am both visualized and invisible, as a symptom of grief and identity.”

Here is a link to “Seeing the Body,” her 2020 lyric video.

LINKS TO MORE ABOUT THESE ARTISTS:

Amy Sherald’s Gallery (L.A.)

Amy Sherald’s Interview in an earlier issue of TQ

Hayv Kahraman’s website

Kahraman’s gallery (NYC)

Kahraman’s gallery (L.A.)

Kahraman’s interview in an earlier issue of TQ

Abeer Hogue’s website

Hogue’s work in an early issue of TQ

Jeremy Dennis’s website

Dennis’s interview in a previous issue of TQ

Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s website

Griffith’s work in an early issue of TQ