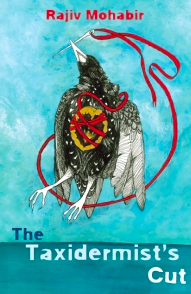

A metaphor that extends across a poem, defying clichés and breaches of clarity or cohesion, is already a feat to be admired. Rajiv Mohabir sees this challenge and raises it 98 pages, pushing a metaphor and its accompanying string of associative leaps to form the rock upon which The Taxidermist’s Cut, his debut collection, is built. Via instructions on how to prepare a carcass for taxidermy, presented as a series of erasure poems from a variety of taxidermy texts, the speaker crafts himself coyote and puts himself on the steel table, a scalpel in America’s hand. “Lets pretend you are going hunting,” the preface begins, “The copper of pine needles falls; / whether you catch me or not is not the point.” We come to hunt the speaker as the preface would suggest, catching him in his cadence, ready to accept pieces of him even in the rhythm of his breath. From a continuity in cadence and linearity of story, if not within a poem, then across poems, we come to see that the poems share a speaker, and that this is the story of his life.

A metaphor that extends across a poem, defying clichés and breaches of clarity or cohesion, is already a feat to be admired. Rajiv Mohabir sees this challenge and raises it 98 pages, pushing a metaphor and its accompanying string of associative leaps to form the rock upon which The Taxidermist’s Cut, his debut collection, is built. Via instructions on how to prepare a carcass for taxidermy, presented as a series of erasure poems from a variety of taxidermy texts, the speaker crafts himself coyote and puts himself on the steel table, a scalpel in America’s hand. “Lets pretend you are going hunting,” the preface begins, “The copper of pine needles falls; / whether you catch me or not is not the point.” We come to hunt the speaker as the preface would suggest, catching him in his cadence, ready to accept pieces of him even in the rhythm of his breath. From a continuity in cadence and linearity of story, if not within a poem, then across poems, we come to see that the poems share a speaker, and that this is the story of his life.

Poems titled for the Latin names of a variety of animals are interspersed with those titled explicitly for events in the life of the speaker, allowing readers a step-wise path to understanding him dually as a person and as an animal, taxidermist and taxidermied. In “Canis Latrans,” the Latin name for coyote, the speaker begins, “do not mistake yourself for a wolf, your plantation days of illiterate indenture still dusk the horizon.” He is establishing early a parallel that will persist: the revered wolf versus the maligned coyote, extant even though when looking directly at them, “white folks see coyotes as wolves.” While America preserves wolves, coyotes are killed as pests. The straight white American flourishes as the gay Indian American is targeted, bullied, and oppressed. “Canis latrans are new to Florida,” Mohabir writes in the book’s eponymous poem, “their pelts hang by the dozens at the Sanford / Flea Market—hated for being exotic, invasive, and competition for jobs.”

The speaker comes to fixate on this perceived failing, “a forgery. Not a wolf,” while his mother asks “why is the child’s body so dark yet speaks like a ghost?” Not white in the eyes of America nor brown in the eyes of his parents, he is liminal. The speaker cannot escape the coyote’s “hide that does not hide.” His battle with identity bares casualties. Within the first section of the book, he reveals that he “no longer cut[s] as a child cut[s].” “Dress for the first time you cut yourself,” he instructs, “blood erupts. New flesh to grow / between these banks of skin. A river first.” In the second section he commands “with a razor, cut.” A large caesura lets the thought linger before he closes “against the commandments of / every book.” These turns hold tension. Religion pushes the speaker to shame, shame for every way in which he defies tradition, for his sexuality, his cultural liminality, and the self-harm that is a result and renewal of his cyclical suffering. The text does not deny the familiarity of this story but embraces it, challenging the reader to become uncomfortable, to recognize that while pervasive bigotry may seem insurmountable it affects real individuals that deserve better.

The premise of the book distances itself from its contemporaries while frequent Ars Poetica grounds the reader in reality and showcases Mohabir’s cleverness: “hide your darkness in lines—” Mohabir writes in “Cutting,” “who reads poetry anyway?” In addition, Mohabir’s use of consonance assures that even in a quiet close there is movement—“I trek the wreckage of myths: / toadstools on a felled tree, or // the crescent-shaped impression / from a hart’s escape to his denning / ground. His hoof print is a split heart.” Later, in the same poem, “Your footprints are covered over / by leaves and other men’s heavy soles.” Hart/heart and Sole/soul are not coincidence, his homonyms echoing the eerie truth of human nature: though perhaps we have evolved we are still animal, we are still subject to the same rawness of desire. Similar symbolism ties one poem to another: blood is consistently rubies, outcast coyote, his father a stand-in for God. These through-lines make The Taxidermist’s Cut a valuable and unique addition to the project book cannon; repetition, voice, and diction the book’s binding and the narrative arc the glue.

Perhaps the most fun part of working through Mohabir’s book is the way in which erasure allows implication. In “Homosexual Interracial Dating In The South in Two Voices (Erasure Poem)” he writes, “A scarlet ibis mounted in a case / on china gasolier, need I warn / against such flights of art? I might / advise upon the subject: keep straight / like two arrows or sticks.” Heavy content is countered by playful presentation and metaphor. Erasure poems and their non-erasure neighbors play off of each other, one presenting instructions and the other contextualizing, one entirely imperative and the other beseeching.

Much of the text functions in such enticing contradictions—from erasure, identity, from erotic pleasure, fear of death. While the relationship between poems is clear, a varied use of form in turns mirrors and contradicts content. Erasure poems speak to assimilation, to expunction of identity, but simultaneously establish the speaker as coyote. The longest poem, “The Taxidermist’s Cut,” intermixes a list, prose poems, isolated lines, and poems that move diagonally across the page, eschewing stichic and more traditional forms. In experimentation Mohabir again separates his narrative from cliché. The benefits of a seemingly consistent narrator can be seen in the book’s final poem, “Catching Lepidoptera at Night,” in which the speaker’s struggle to establish and embrace his identity under constant societal and familial pressure gives way to the beauty of self-acceptance: “Your father’s god says, / If your right hand causes you to sin cut it off— / you would be handless, lipless, cockless. Tonight, / give him back his god. Don’t trust his words.” The closure afforded by such a clear arc of innocence to adversity to acceptance is admittedly somewhat saccharine, but incomplete. Though the speaker has grown and changed, America has not. Even if self-loathing has been conquered, external discrimination remains omnipresent.

Mohabir’s narrative is manifold—in the backdrop of America’s intolerance lies the speaker’s coming-of-age story, the loss of his virginity and his subsequent sexual adventures running parallel to a story of societally induced ostracization and depression. His relationship to his father, to his roots and to his current home pull together a complex narrative across a field of formally and sonically diverse poems. The narrative and political nature of the book calls to mind Cornelius Eady’s Brutal Imagination, while the style and organization, clearer narrative poems interspersed with titular content poems, mirrors Marianne Barouch’s Cadaver Speak. There is much for a reader to explore and revisit, particularly if their interest lies in an amicable yet rebellious speaker, a character to become attached to, a rarity in poetry books that amps up accessibility and engages the reader by the end of line one. To fully grasp the book’s strengths, one must sit awash in both what is given and what is purposefully omitted, in the blank spaces to be read like a Rorschach, each reader taking home what they please.

Joey Lew is a MFA candidate in poetry at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She holds a Bachelor of Science in chemistry from Yale University, where she was a member of WORD: Spoken Word Poetry. An interview that she conducted is forthcoming in Diode.