The collection’s first poem is a call to attention. A tolling. “Belle,” and its homophonic first line, “The heart is a bell,” set the stage. The grandmother has fallen ill, tapped for death: “Push / the sternum and hear the church / doors crack.” This line is followed by a desperate cry to God—a complex yearning intertwined with regret, shame, and a sort of indescribable mourning. A belated begging for prayerful help. Habitual, though unpracticed, requests are made to God: “Parishioners sludge in / The pulled tongue sounds.” This sludge. Slow, thick, and overwhelming. Vulnerability is the poet’s pure response.

The collection’s first poem is a call to attention. A tolling. “Belle,” and its homophonic first line, “The heart is a bell,” set the stage. The grandmother has fallen ill, tapped for death: “Push / the sternum and hear the church / doors crack.” This line is followed by a desperate cry to God—a complex yearning intertwined with regret, shame, and a sort of indescribable mourning. A belated begging for prayerful help. Habitual, though unpracticed, requests are made to God: “Parishioners sludge in / The pulled tongue sounds.” This sludge. Slow, thick, and overwhelming. Vulnerability is the poet’s pure response.

Readers bear witness to Jackson’s personal ceremony—but nothing is definitive, nothing is explained. Instead, she uses gesture and imagery to do the work. In “Home-Going,” she writes, “Spectators tangled in your drawn net surround / your hammock salt and map your body: // repast.” The metaphor of a spider catching its prey conveys a natural brilliance, a web of interconnectedness, patience and perfect design. But such understanding of nature does nothing to relieve pain. Within this collision of desire (for life) and necessity (for death), there is desperate hunger for a body because it is leaving.

In “I Bury My Dead a Second Time,” Jackson devotes an entire line to one word, an ancient Hebrew term found seventy-one times in the Book of Psalms: Selah. Loosely translated, selah means, “Pause and think.” Within the interlude, past and future are eschewed. Only the present moment exists. By proclaiming selah, Jackson seems to say, “This is how we will mourn.” Her rectitude delivers hope.

“After We Lost Her I Refused to Give Anyone More Than Ten Words” is more cinematic. Gaping mouths and cavernous throats lead readers into darkness, down tunnels, into graves. The poem functions like a mantra, cyclical and repetitive, inviting readers in. Like a call and response, like an echo, it gives away its voice as a gift:

The mouth opens like a grave

*

Our mouths open like her grave

*

Our mouths: her grave thick-

tongued cavern From our throats she blooms

Sunday hymn toward a quiet sky

*

Thick-tongued quiet Our mouths

caverns graves Our throats

bloom a Sunday sky hymn

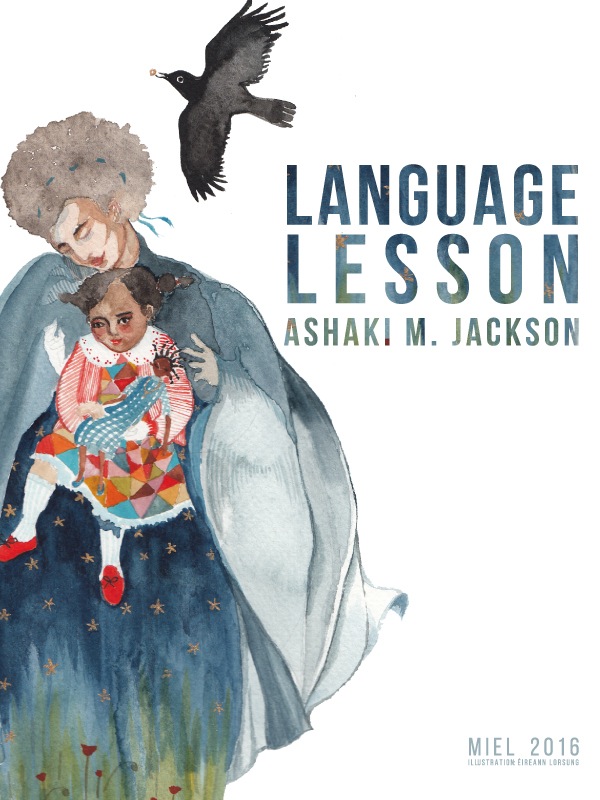

Jackson’s poetry is brimming with images that suggest a metaphorical consumption of the dead. “Gathering the Bones” contains an epigraph for Cecilia McCallum, author of the 2001 Amazonian ethnography, How Real People are Made. Language Lesson’s eating metaphor parallels McCallum’s study of Peru’s indigenous Cashinahua people. Jackson writes, “The body: / around here somewhere // The ashes finished // We forget // That was how they ate a body in ancient times.” An earlier poem, “The Anterior,” extends this consumption and infers nourishment. “We choke on old language,” and, “hollow bellies cradle farewell songs tongues.” Then, later in the same poem, “We pat together new mother of roux / dough / loneliness.” This ingestion of flour and fat, of earth and flesh, slows the stutter of despair.

“The Body Has its Custom” represents Jackson’s efforts to make meaning: “The stars recall what they have always known: heat / and how the body opens quite suddenly / to the universe’s black tongue.” These “stars” are the human condition. The “heat” is disease—a harbinger of loss. The poem continues, “See a night rashed with constellations and consider / why the body breaks / publicly // how we carry our shattered selves / into all spaces.” Most poignant, most tragic, is the social statement therein. Must our deepest emotions only be held secretly? Such inquiry universalizes the poet’s personal suffering.

Near the end of the collection, two poems use other bodies to tell a similar story of paralyzing loss. “Center of Gravity,” begins with a caption of an EPA photo published after the 2014 disappearance of a passenger airliner over the South China Sea: “Liu Guiqiu, the anguished mother of a passenger from Malaysia Airlines flight MH370.” The words that follow compare the poet, also a survivor, also one left behind, to the distraught mother who crumbles, open-mouth howling, into a flood of strangers. Jackson writes, “Your drenched silence will kill her / She is human / in her hyperbole.” The poem ends with, “How too the force of Mother’s body swallows / She wants you returned / none of us are prepared.” It is difficult to determine whether Jackson is referring to the woman in this photo or to herself, but both are relevant, both applicable.

The book’s penultimate poem, “The Body of an American Paratrooper,” is also preceded by the description of a press photo. It reads, “The body of an American paratrooper killed in action in the jungle near Cambodian border is raised up to an evacuation helicopter.” Taken in 1966 by French war photographer Henri Huet, the original photo frames a dead soldier’s body being lifted into the hovering aircraft. The hoisting cables are not visible, so the lifeless body seems to float above the battlefield. Rising Christ-like, even.

This body:

a question and broken

compass North-pointing or ascending

and bruised like a savior

| The body is dead |

Fully clothed and suspended in a truth-

ful place

This “truthful place” is a place where the body (and the poet) are at ease. The poem continues, “When I say truthful I mean honest / as skin | A loose / tongue | I’m saying ‘obvious’.”

Language Lesson is a personal rite, a ceremony of sorrow, a gripping writhe leading to an eventual return. A song nourished by conscious submission:

Sure his mother will open

her wail mouth brimming

his iridescent plumage Her body too

passing through

surrender

Tom Griffen is a North Carolina poet with California roots. In 2015 he received his MFA in Poetry from Pacific University. His work has appeared in Prairie Schooner, Crab Orchard Review, Harpur Palate, O-Dark-Thirty, The Quietry, and others. Tom is also an ultramarathoner, a reflexologist, and a freelance retail trainer in the specialty athletics industry.