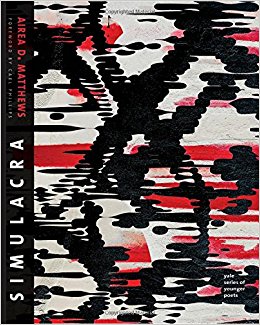

Airea Matthews’ debut collection, Similacra, is an experiment in time travel, a self-examination that takes place by means of a non-linear journey through civilization. Matthews employs a council of writers, philosophers, musicians, and mathematicians – along with a pantheon of deities spanning multiple cultures – to pull back the veil of the mundane and reveal personal truths. She dons a series of masks through which we can view this story, and ultimately takes them all off.

Airea Matthews’ debut collection, Similacra, is an experiment in time travel, a self-examination that takes place by means of a non-linear journey through civilization. Matthews employs a council of writers, philosophers, musicians, and mathematicians – along with a pantheon of deities spanning multiple cultures – to pull back the veil of the mundane and reveal personal truths. She dons a series of masks through which we can view this story, and ultimately takes them all off.

The titular “simulacra” refers to French philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s concept that likeness uncovers the truth – the examined thing is, in fact, the thing itself. Matthews uses a changeable character to personify her simulacra. Sometimes it is “Rebel”, from the Camus epigraph that opens the book. Rebel warns us up front what we are in for; in the opening poem she reflects “...I knew it was a winged thing,/ a puncture, a black and wicked door.” Other times her simulacra is “Want”, who, when we first meet her, tells us “I see through you...Nothing to see. Not much to your kind.” The simulacra is perhaps best personified by Narcissus. Fascinated with his own reflection in both the literal and figurative senses, Narcissus frequently appears in a water motif. He invites us to “Imagine that you are sitting by that pond only to find that you are the water and you were very, very thirsty.”

If Narcissus thirsts, for self-knowledge, for love, Matthews’ simulacra possesses an even more compelling urge – intense hunger. The metaphor of the hellmouth appears repeatedly in these poems. Classically, vagina dentata is female, and represents male fear of being consumed by female sexuality. This version does present in “The Good Dentist’s Wife”, where the self-sacrificing spouse allows her husband to remove her teeth one at a time as a proxy for the desire he has to possess other women. The good wife, thus disarmed, is at his mercy, and he “thrusts his tongue in her mouth, massages the bald ridge where her crown once was, where the root hid – renewing their vows in a covenant of bloodlust and sacrifice”. This poem appears early in the collection, but aside from this one piece the gender role is flipped. It is a man’s mouth that produces bone, blood, soot, tar, and the poverty of teeth that marks loss of power. In “The Mine Owner’s Wife” the owner has a “coal-mine mouthshaft” and drags “his fork’s sharpened time against his lip”. Matthews uses mouth/hunger imagery to give voice to the fear of being swallowed, being subsumed by one’s own genetic heritage and personal history. In several poems we meet the “father” – “a moody bastard genius” whose mental illness and related drug use threaten to engulf Matthews’ speaker. In “Rebel Opera”, a poem written as stage directions, mother and daughter (Rebel) spend their days propping up a failing patriarch, “flossing and brushing his one remaining tooth”. Their efforts fail; in the end “FATHER: (swallows)”.

If Matthews’ protagonist struggles against a tide of starvation, she also has allies. She leans on her books, and the people she has met within their pages, to help her navigate her internal world. One of these appears in the form of an (imaginary?) nurse the speaker meets when she is committed to a mental health facility. The nurse is (coincidentally?) named Anne Sexton, and along with managing the speaker’s medications and taking her blood pressure, she provides a sounding board for the speaker’s struggles. Often these conversations take place via text messaging. As “Dead Addict’s Daughter”, the speaker discusses with Sexton how to survive a polar vortex wherein “every slick black/lies under rock/salt”, and father is always dying “for the last time/on a Monday, or a Tuesday or/Wednesday or was it Thursday or/Friday?” As “Ingenue”, she seeks Sexton’s electronic advice about “The Honey Moon” and “squandering impulse” – are her talents wasted on domestic life and family? As “Quiet Desperation”, she and Sexton exchange five pages of text on this intimate subject – might it be better to flee in the middle of the night, and follow Gomer, Jezebel, and Tamar on a road which, though it leads to hell, might be more personally fulfilling?

Matthews’ speaker also cherishes a close relationship with Gertrude Stein. The poet melds with the speaker’s southern grandmother in a virtuosic rendition of Stein’s language based poetry – “Lark fed. Corned bread. Bedfeather back. Sunday-shack church fat.” Stein also appears as her spiritual guide on a Paris train, pushing the seat buttons, asking “what verb are you?”, and naming her “purple” – an outrage to the speaker, but also an intimation of royalty, a recognition of “blood red. blue blue”.

Matthews uses every weapon at her disposal to battle her speaker’s fears of mental illness, substance abuse, loss of power, and emotional entanglement. She’s selecting from a formidable arsenal. Her skill with form and pacing allows Matthews to range between carefully controlled stanzas, extended prose poems, text messages as convincing poetic conversations, and even a series of tweets from (who else?) Narcissus to other mythological Greek characters. Matthews leverages her broad classical knowledge to harness skills from a variety of disciplines. In “Dodecophony” she mimics a compositional form and weaves the ribbons of music, math, and language to create stanzas which have perfect word balance. In “Blind Calculus” she dazzles – and possibly confounds – the reader with a poem employing mathematical symbols – “ (β) divided by it (Ω) plus her ≠ µ plus √” and closing with a lemniscate – the infinity symbol. And of course, Matthews draws from widely ranging cultures. In addition to Greek mythology and biblical characters, we meet Salem’s unfortunate Tituba, the South African lightening bird Impundulu, and Egypt’s Sekhmet – the goddess of war and healing.

It is Sekhmet who begins to take ownership by the collection’s end. Though she knows true resolution is a conceit, a vain attempt to “reveal this enemy’s backbone,/ uncoil that helix”, she nevertheless sallies forth into battle. In “Sekhmet After Hours”, she admits to a “full-blaze feral ego” but tells us “famished ghosts/ can never be full, even after breaking fasts.” and hopes “not to face another of our undoings”. It is as Sekhmet, lion-goddess, sun-bearer, that Matthews offers us a way forward – “isn’t it true, at some point,/...a stone/ thrown upward with great velocity/will escape humble gravity?” The gravity, the graves, the ghosts, haints, and hungry mouths of the past can be left, if not behind, at least below. Matthews concludes with an aubade, of sorts, taking us in hand, “...should what swallowed us/not quite kill us,/.......hail dawning, curse damning” and reminding us to “...live in violet/and breathe in mystery”.

Sonja Johanson has recent work appearing in The Best American Poetry blog, BOAAT, Epiphany, and The Writer’s Almanac. She is a contributing editor at The Eastern Iowa Review, and the author of Impossible Dovetail (IDES, Silver Birch Press), all those ragged scars (Choose the Sword Press), and Trees in Our Dooryards (Redbird Chapbooks). Sonja divides her time between work in Massachusetts and her home in the mountains of western Maine. You can follow her work at www.sonjajohanson.net.