Maybe more so than other texts, Sylvia Plath’s Ariel is impossible to read outside of the biography of its author. Who can read Ariel away from her suicide, her poet-philanderer-husband, her children, her marital breakdown, that desk piled with papers, that kitchen, her body to find? The 2004 edition opens with a preface by her daughter Freida Hughes, who decries the use of Plath’s poems by “strangers” who “possessed and reshaped” them, making Ariel, “symbolic . . . of this possession of [her] mother and of the wider vilification of [her] father.”

Maybe more so than other texts, Sylvia Plath’s Ariel is impossible to read outside of the biography of its author. Who can read Ariel away from her suicide, her poet-philanderer-husband, her children, her marital breakdown, that desk piled with papers, that kitchen, her body to find? The 2004 edition opens with a preface by her daughter Freida Hughes, who decries the use of Plath’s poems by “strangers” who “possessed and reshaped” them, making Ariel, “symbolic . . . of this possession of [her] mother and of the wider vilification of [her] father.”

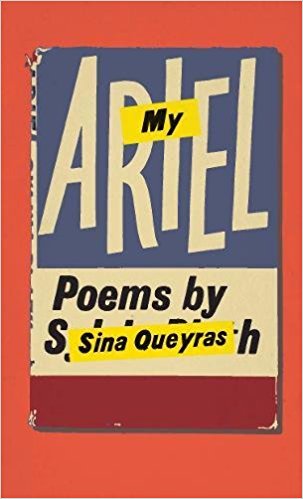

In her new and astounding collection, My Ariel, poet and critic Sina Queyras possesses and reshapes the poems of Ariel, but not in a way that tries to possess Plath or vilify Hughes. Instead Queyras revivifies them, combining elements of the lyric and confessional we associate with Plath with poems that demonstrate the biographer’s research, a kind of found poetry made from letters and criticism and fact. The total effect is to so defamiliarize the poems of Ariel as to give them new urgency, an urgency moves them from 1960s America to the preoccupations of our own time.

In blurbs, Queyras’ collection is called a “poem-by-poem engagement”, but the twinning and echoing is far more widely and wildly dispersed than that. The opening section, with riffs on “Morning Song” and “Daddy” does seem a more one-to-one engagement. You can read “Morning Song” like a puzzle of allusions. “A love procedure set me going like a big fat lie”, and in Queyras’ take, the speaker is giving birth not to children but to Tweets. Flickers turn Flickr. Plath is an addressee, as she is in many of the poems. The speaker wonders

Am I any more authentic than the account

That Tweets your verse?

Or the cloud that archives your words?

Or the screen on which your poems float?

The Twitter account of “Sylvia Plath” usually tweets intense Plathian lines and sometimes joltingly recommends clickbait. Poetry may come to seem algorithmic, the poet taking in the archive and spitting lines out. And My Ariel is a kind of archive of Plath’s words, intermixed with many other voices: Ted Hughes’ letters, Janet Malcolm’s commentary, Anne Carson, Virginia Woolf, Elizabeth Bishop, Gertrude Stein, Anne Sexton, and on, and on, as well as pulling in digital and popcultural parlance, in lines like “Becky with the new shade” and “The pixels of Donald Trump’s face”. But this mix of letters, biography, poetry, film, Facebook posts, songs, Tweets is sent though the poet’s consciousness and becomes a collection of lyric work that gives pain and channels rage.

In the second section, a long poem that reads like compelling biography, the pace picks up. “Years” splices Plath’s biography with conversations the speaker has with her mother, and the speaker’s identities slip. Sometimes she is biographer, sometimes reader, sometimes she slips into confession. The effect is wonderful:

I read the poems, and then slide between the poems, scour what has

Survived Ted’s censoring. I read Ted’s letters, then

Yours. I watch Gwyneth Paltrow move her shape-shift good-girl

Form with stoic passion through a moorish scene, there is your wild

Yard, and my mother in her heels, a knife down in the turf, beheading

Dandelions. I sorry I can’t keep the two strands apart

Later, the speaker interjects, “why am I telling / you this?” By the end of “Years”, the speaker’s mother and Plath are both formidable mother-figures:

Love, hate. How can I escape the force

Of her narrative, how she pulls everyone

And everything into her design? Then,

How will I survive without her voice?

Her narrative, her design: Plath’s, Queyras’s, her mother’s.

Some of the poems are more plainspoken, lineated but reading like prose, while others are urgent and forceful prose-poems, while still others have biting, stinging wordplay, as in “I Am No Lady, Lazarus”: I am a dark clown blown. An umlaut in a grim / Gown. I bite down.” In Lazarus, there are lines I want for tattoos (or Tweets?): “My ambition is not pretty. / My feeling is not a good colleague. I am not your affirmation machine.” Ambition, poetic genius, and gender are a persistent theme through many of the prose-poems of the third and fourth sections. From “The Secret”:

Too bad you

weren’t a man. The worse you behaved, the louder the critics would

have raved: Unstoppable, they’d say! So much herself! Sure, she

slaps a man now and then, begs them listen intently to her aspira-

tions, but she’s a genius, and we all know how ‘difficult’ genius is.

Bend over, you’d command, and they would wiggle and squawk,

brushing the soft tips of their careers against your hips.

…

For God’s sake, hold your cock and let her write.

I began to read too quickly as the work became so propulsive and I was starved for it, as a sensitive young woman is hungry for Plath. I needed the life it could show me, the rage laid bare (“For God’s sake, hold your cock”) in the midst of our news cycle’s revelations of men sexually assaulting and gaslighting talented women. Queyras’s “The Moon and the Yew Tree” pleads breathlessly after the breathless repetitions of its long prose lines, “Women? Where are you now? Oh, come / and bang on my door. Come and tell me about what lies outside the ‘I’”.

Queyras has written numerous award-winning books of poetry and prose, and is an influential teacher, poet, and critic who lives in Montreal. Thank goodness for her influence. The collection ends with a poetic record of new parenthood. Queyras has said in interviews that having children made Plath more important to her, and this comes up in the poems, too: “It wasn’t until / the babies came that I could really turn to you”. I have rarely seen the pain of new parenthood examined with this kind of depth. How dark it feels to lose the self, to feel annihilated, and for the agent of your destruction to be your love for your helpless children.

In “Double Fantasy; Or, Motherhood Is a Young Woman’s Game”, the speaker morphs again, broken down into a new role as the partner not bearing nor nursing the children and so both inside of and outside of motherhood. The inside-confessional/outside-biographical movements are intensified: “I am observing myself observe”, she writes. She is more like Ted now, like her own father, the partner supporting the partner giving birth. The excruciating difficulty of parenting gives us these lines: “I cannot recognize myself at all. I am all shortcomings. All lack” and “Can no one see / how half my face is torn off? How my mind is shattered?” and “My mediocrity pooled around me, lapping at my psyche, Write, / write, it said, or you are done” and, most painfully, “Will I also eat my children?” These poems are beautiful, and true, because parenting is impossible, because we need role models, because Plath needed them. How else are we supposed to do all this? How are we supposed to manage all these feelings, all this ambition, all this responsibility?