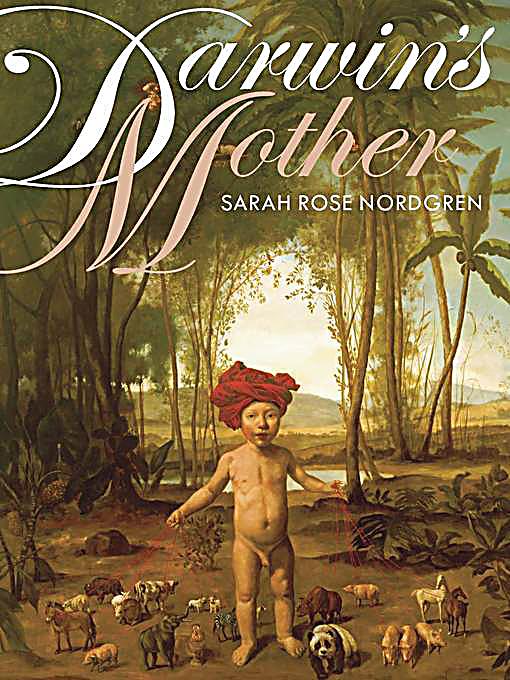

Sarah Rose Nordgren’s second book Darwin’s Mother, from the University of Pittsburgh Press, borrows stories and voices from a wide range of scientific communities. Her book exemplifies contemporary poetry’s longstanding traditions of defamiliarizing human activities and imagining life beyond a human-centered world. In doing so, Nordgren delivers massively complex ideas in everyday language. She plays with persona to challenge the belief that humans are the supreme species. She questions science in a way that is weirdly warm and coldly humorous, often pointing to the beauty of raw data and a life beyond being too human. Altogether, Nordgren gives concise analogies that experiment with topics and issues of posthumanism.

Sarah Rose Nordgren’s second book Darwin’s Mother, from the University of Pittsburgh Press, borrows stories and voices from a wide range of scientific communities. Her book exemplifies contemporary poetry’s longstanding traditions of defamiliarizing human activities and imagining life beyond a human-centered world. In doing so, Nordgren delivers massively complex ideas in everyday language. She plays with persona to challenge the belief that humans are the supreme species. She questions science in a way that is weirdly warm and coldly humorous, often pointing to the beauty of raw data and a life beyond being too human. Altogether, Nordgren gives concise analogies that experiment with topics and issues of posthumanism.

Early on in this book, Nordgren takes on the point of view of a weed. She begins her poem, “The Weed,” by offering, “The weed wants so much / to hurt like an animal.” As throughout these poems, plants, animals, test subjects, humans, and even a being of artificial intelligence, all strive to be more alive, more like another species. Here, the weed does not want to be human, the weed wants to be an animal, suggesting animals may be superior to human in their experiencing of hurt or pain. While humans must sometimes swallow their pain, animals might not, and the weed perhaps observes this. Nordgren also takes on the voice of a test monkey from a famous psychology experiment. She takes on this voice to return a sense of humanity to a submissive test subject. This is something she does throughout the first half of the collection, giving delicate attention to the bones found in archeological site and, as the titular poems suggest, Darwin’s own mother. In “Virtus et Scientia,” Nordgren grapples with the dehumanizing aspects of science and human progress:

We maintain or notes, but Progress only

inches forward on its hundred frail legs.

Numbers for degrees of movement.

Numbers for degrees of stillness.

Feelings have very little to do with it.

Progress is another theme that plays out complexly through these poems. In this poem, human progress is presented in the image of a clumsy millipede; some legs do not move in unison with the rest. As with many poems, here Nordgren takes on the voice of a scientist collecting notes and observations. She plays on the notion that poets are part of a scientific community. Notes formally end her book of poems and shed light on the research she performed while writing these poems. Throughout her poems, she involves readers with bits of biology, animal psychology, and Darwin’s biography. All of this helps drive along the greater theme of evolution, which Nordgren continuously questions.

Linearity and technology have paradoxical relationships with evolution in this book. In some respects technology educates people about other cultures, however problematically. In one poem, “An Uncontacted Tribe,” Nordgren writes:

The camera’s powerful

zoom lens allows us to film

from more than a kilometer away, causing

minimal disturbance to the tribe

the government denies exists.

While taking on the topic of ethics in science and anthropology, Nordgren imagines jungles and indigenous tribes, which Westerners might be able to learn from. Primitive life in the wild is romanticized in greater detail later in the book. In this poem, the mechanical tools of science are made strange. In other respects, technology later pushes human consciousness in the reverse direction, from psychological control. In a later poem, “Electromagnetic,” this theme takes on a lamenting tone:

“Too bad

technology has overridden the soul

and we can no longer experience

true thinking. Not even

the President has power

anymore.” You share this fact...

Nordgren urges readers to confront the extreme powers of technology. In these two instances, technology serves as a means of validating reality and obscuring it. More importantly though, Nordgren highlights the notion that scientific data is at once both invisible and visible. She explores beauty in the age of cacophonous information.

In her poem entitled “Reservoir,” Nordgren makes readers imagine all of the data created by our civilization collected in one place. In defining data for her poem, she throws more than medical records and personal emails together, forming “the lake of digital blue, / the infinity of opaque surfaces / refracting sunlight.” She goes on to explain this reservoir as a tourist attraction. But when read against the other poems in her book, the data mentioned in this poem takes on an inhuman or posthuman presence, as if the data we create makes up something beyond humanity. Her final poem “Mindfile” runs with this theme, tackling the notion that a person is the sum of their personal information or data. The speaker is a woman’s consciousness placed into a robot:

You didn’t forget me at the hospital

like I feared you might–for

you always cared what would happen

to your files. You kept good track...

The philosophical discussion captured in this poem is light and more cinematic than a doctrine or manifesto. Yet, people have been transformed into data and the poem is about this data itself. To a certain extent, many poems collect and present the data of a speaker. Like the cybernetic woman in this poem, a poem is a machine that delivers data and desire. The imprecise science of this notion lies in how that data is then processed by the reader, who desires thoughtful engagement, which this book greatly delivers.

At the heart of this collection Nordgren explores human desire. While science desires progress, it is entirely possible humans desire something else. Determining what it means to be human in this age is a perfect topic for poets to frame. Nordgren leads such poets in presenting us with subjects and radical glimpses of different futures. The digital reservoir of data will rise higher and we will have our eye on the jungle, as echoed in lines from “Electromagnetic”:

A return to primitive, real life.

Fruit and sex and weather

and genuine work. Illness

could be mystical again.

Readers and poets alike will need to grapple with the big paradox this little book lays out: Maybe a way forward is a way backward and a way backward is a way forward. Regardless, with STEM on the rise and the humanities in danger, this book is for the posthuman in all of us.

Mark Hausmann earned his MFA and MA in English from Chapman University, where he is a composition instructor. He won the John Fowles Center for Creative Writing Award for Poetry in 2017. He writes both fiction and poetry. He is from La Habra, CA.