No one here explains all the noises.

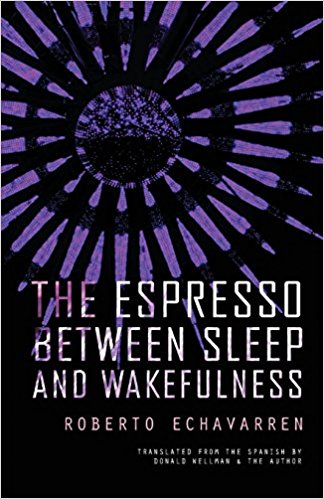

“Rooted in surrealism,” reads the note on Echavarren at the end of Donald Wellman’s translation, just as I had imagined it would. You don’t need it to tell you, Echavarren’s poems are more than happy to speak for themselves about everything out of the ordinary. The bilingual edition provides each poem twice, first in English and then in the native Spanish, as two separate versions within the same volume. In that sense, it is not literally bilingual—page by page, it’s either all English or all Spanish.

It’s unclear whether the book benefits from this choice, or whether Echavarren himself had a say in it; Cardboard House Press only trades one advantage for another, avoiding the sense of dislocation in bilingual spreads but lacking the unity and conversation of two languages lined up alongside each other.

I don’t know if I fit in here

and yet I am here like the edge

of a coin flipped in the air.

When it falls, it will show

the face to be read.

Echavarren, stumbling through a challenging juxtaposition of scenes seeking some kind of identity, leads with the first-person at every opportunity. Our experience of it as readers of English is in some ways only a quirk of translation: in Spanish, “I don’t know” is merely “No sé,” and while certain verb tenses obligate the speaker to identify themselves with a pronoun, the reflexive Spanish “me” (pronounced somewhere between “meh” and “may”) is still a far cry from the emphatic “yo,” the egoistic first-person singular. Absent the pronoun that we identify so strongly with a speaker, the Spanish reads with a slightly different character than Wellman’s translation.

Rather than decry what Wellman necessarily loses, this is worthy of celebration, the ability to find new forms through the play of language and its rules. Wellman does take a few aesthetic liberties with the translation, adding or deleting line breaks where one could easily have chosen to preserve them, as in “The Rape of the Lock,” where the full line:

Un pariente respinga y endereza el cogote para decir

becomes—

A relative balks

and stiffens his neck while saying

for reasons of emphasis alone. But poetry is perhaps as difficult as translation gets, and it is easy to forgive the fairly small tweaks that Wellman makes to smooth over an otherwise challenging ride.

Challenging, in the sense that Echavarren is committed to his understanding of surrealist imagery. Where two lines together might form a familiar and comfortable image, hardly a stanza passes without finding that image conjoined to another image totally out of sorts with the first. Though Echavarren doesn’t quite live up to surrealism’s most enduring definition (the “chance meeting upon a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella,” in the words of its manifesto) he moves fast and hardly gives the reader time to breathe, a quality of what appears to be his own personal journey through the poems. Though difficult to say how closely Echavarren identifies with the speaker, or if the “I” is only his canvas, a model for some internal conflict, he is clearly reaching for a specific feeling and experience, which not every poem achieves but at least acknowledges.

Wellman renders Echavarren’s free-verse lines with even pacing and a keen attention to the emphasis of syntax. English feels the absence of rhyme on a deep level, with a jagged rhythm that only lends itself easily to a few meters without getting bent out of shape. It is difficult for English speakers, given a long history of traditional formal rhyme, to read this absence as anything other than a radical break with the past, or a kind of nostalgia for its loss. English has a leg up, in some ways, on the future of poetry, on a collective feeling of fragmentation and dislocation in a bleak modern landscape. We’ve been trained for irregularity. Romance languages, on the other hand, are tied into their own history through the structure and legacy of the language itself.

Spanish nouns all end alike, with either a feminine -a or a masculine -o. Unlike the countless irregular variations of English verbs, Spanish has only three major schemes of conjugation, aside from its own relatively small set of common irregulars. Even in unrhymed free verse, Spanish lends itself to sound and one can hear the rhythm of Cervantes in new Spanish surrealists in a way that Milton will never echo in the English of Charles Simic, or Robert Bly, if only because the language doesn’t offer any bridge to the past.

Though it hardly possesses a narrative, and the surreal character of each poem makes it difficult to actually place any of them as more than a feeling or combination of wild experiences, the arrangement of the whole book possesses what some might call a plot, in the sense that the journey from beginning to end acts as a kind of arc and demonstrates to the reader a definite change. Echavarren opens with the titular “Espresso Between Sleep and Wakefulness,” posing what follows as something more than a dream but tied in to the darkness of sleep, not yet able to escape its gravity. Even as he moves farther into the collection, Echavarren can’t resist variations on the same images:

whirring tires on the wet macadam in “Espresso,”

the horses’ hooves on the macadam in “Inquest,” and

a violet / dark blue ocean of wet macadam in the final “Goddess,”

Dragging a skillful and subtle thread through the collection without the monotony of repetition.

Most importantly, he ends with “The Goddess,” a long take on eroticism and identity that acts as a sort of key to the rest of the collection. The great jumble and confusion of earlier poems softens under the relatively calm (but unconsciously tense) final pages, passing from the realm of early wakefulness, of being “drunk on espresso coffee / [to] go out at express speed” to a definite reality, a place and a body whose shape Echavarren identifies with the hair of a goddess, even as he blurs its other outlines and drapes it in mystery. Here, Echavarren emphasizes his pronouns, and Wellman reflects it, with constant reference to “he” and “his,” carefully reserving any feminine expression for the moment when “La Diosa” emerges in her own form, with a male fisherman who finally

…untied the knot of hair

with his free hand, and felt the whiplash

of the wet ponytail on his rump.

Shaken, shot through with caffeine, the collection is confident and knows when to allow itself total freedom. Wellman is two titles behind a growing oeuvre; whether or not Echavarren finds success in English publication, he is a poet of great feeling and solidity; one gets the feeling he will advance from language to language without much caring who stops to look. All the same, we do.

B.C.A. Belcastro is a poet and political activist whose writing has also appeared in Spires and Thesis XII. He lives with friends in Bronx, NY.