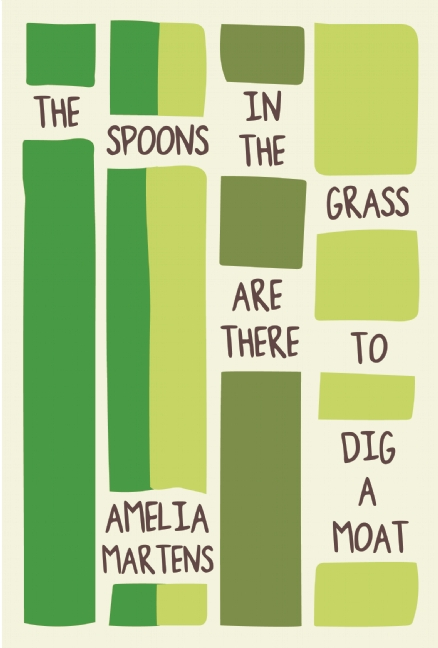

Amelia Martens’s debut collection of prose poems, The Spoons in the Grass Are There to Dig a Moat (Sarabande, 2016) is a successful, surprising, and darkly humorous rumination on contemporary public, domestic, and divine life. The unassuming nature of the prose poem’s form, coupled with a childlike philosophy regarding life and death, effortlessly invite readers into the worlds this book creates. As it does so, Martens establishes herself not only as a serious prose poet, but as a prose poet with something new to offer the genre.

Amelia Martens’s debut collection of prose poems, The Spoons in the Grass Are There to Dig a Moat (Sarabande, 2016) is a successful, surprising, and darkly humorous rumination on contemporary public, domestic, and divine life. The unassuming nature of the prose poem’s form, coupled with a childlike philosophy regarding life and death, effortlessly invite readers into the worlds this book creates. As it does so, Martens establishes herself not only as a serious prose poet, but as a prose poet with something new to offer the genre.

The collection opens with an apology, or at least, a poem called “The Apology,” as if to assure her readers that this is indeed a poetry collection:

And the apology I made for you came from a willow tree. From a lemon. From some mud I found in the living room. Our daughter thinks you are a giant. She asks you to lift the house, so she can put her dolls in timeout. There is a crack in the back of my mind and I am filling it up with forget-me-nots and sailor’s knots and do nots...

Martens employs traditional poetic techniques: word play and rhyme, such as that between “forget-me-nots and sailor’s knots and do nots,” as well as the anaphora of “From...” and later, “I should.” This poem satisfies readers’ expectations for poetry because it maintains many of the hallmarks of verse. But perhaps the apology in this first poem is an apology to readers whose expectations Martens plans to thwart over the course of the collection. Rather than continue to present “traditional” prose poems, or ones that contain recognizable poetic techniques, many of the subsequent poems use plain language to match prose’s ability to capture the ordinary. And yet, what makes these prose poems prose poems is their graceful, uncanny, narrative compression. This is not to say that all of the subsequent poems eschew poetic convention. Rather, they use language to create situations by which the divine may enter the mundane in order to render ordinary situations extraordinary, and extraordinary situations ordinary. The Spoons in the Grass lures us into the various domestic worlds and lives of the characters who inhabit them.

About one-third of the poems in the collection feature a blue collar Jesus living a life that often resembles our own mundane lives. Jesus works a drive-thru. Jesus runs a factory. Jesus leaves the bar on a Wednesday morning. Occasionally, these Jesus poems occur alongside national disasters: the Boston Marathon bombing, the Newtown shooting, and various unnamed wars. The overarching sense of tragedy conveyed in poems like “Marathon” and “Newtown” is that God, too, is powerless to these make terrible things go away. “Newtown” in particular calls attention to the ways God is both present and absent in the face of disaster; Jesus is there, in the aftermath, but he is passive. He is “like a cement statue,” unmoving. He “sits,” and “There is nothing he can do.” Likewise, the only thing the Newtown people can do is curse God’s name. The poem engenders a Jesus who feels the pain of this tragedy—“thorns turn like screws” on his head—but like us, he, too, feels incapable of offering any real help or solace.

In turn, poems that use the speaker’s daughter as a subject astound with their insight. As entries into a child’s mind, these poems uncannily enfold us into a perspective that is simultaneously logical and not. For example, in “Late Night Comedy,” the speaker’s daughter wakes from a nightmare and “wants to know if monsters are alive.” Knowing that “Monsters are alive, somewhere,” the parents want to give her an honest, unthreatening answer, but they can’t. In fact, the child already knows “We are monsters, momma. And we don’t even live under a bridge.” While the speaker sees this as an opportunity to discuss “The unnamed unknown, a problematic point of view,” she cannot explain monstrosity any better than the daughter already has.

This precocious daughter also explains death rather intelligently. In “Coming Forth to Carry Us,” the child practices dying on the bathroom floor. “What am I doing? I’m dying. You close your eyes when you’re dying.” The child directs the mother and the dog to close their eyes and do the same. To “Be dying.” Like “Late Night Comedy,” this poem likewise captures a child’s acute sense of reality. As this poem reminds us, we do not only forget how much children know about death, but how much we ourselves do not know. The child’s sense of death in this poem is both candid and accurate: “You are dying.” A simple, terrifying, revelation.

What is perhaps most astounding about this collection is that Martens has carved a space for herself within a genre that has primarily been dominated by men. These prose poems are not descendants of French surrealism, nor are they fabulist in an Edsonian sense. They are not object prose poems, like those of Ponge or Bly. Over a decade ago, Holly Iglesias pointed to the absence of women’s prose poems in anthologies and journals, arguing that these were excluded because they did not adhere to the standard mode of prose poetry (as surreal or fabulist). As Iglesias notes, this standardization completely undermines the prose poem’s “anti-genre” thrust. While Martens’s poems occasionally read like parables or vignettes with a capaciousness for strangeness, they are not absurd or otherworldly. They are lyric meditations on motherhood and disaster. Their humor relies on the surprise of the ordinary, not the surreal. They resist separating the divine from the mundane. Ultimately, the worlds in these poems feel like worlds turned upside down and backwards and inside out—until we realize we have been unapologetically shown the very world in which we live.

Hannah Dow received her PhD from the University of Southern Mississippi’s Center for Writers. Her poems have recently appeared or are forthcoming in Cincinnati Review, North American Review, and Ninth Letter, among others. She reads poetry for Memorious: A Journal of New Verse and Fiction.