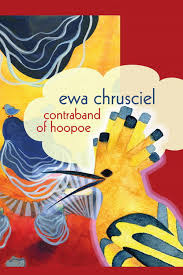

Ewa Chrusciel’s new book of poetry, contraband of hoopoe, asks its readers to do the work of not just reason or the sensuous but to engage their sensuous reason. Chrusciel is asking us to not only conceptualize or make real her vivid imagery in our mind’s eye, but to feel the bones and feathers of the hoopoe move against our skin—cross barriers—as reading becomes experience. In the movements between approbation and interrogation, we are left unsteady—opened up between thinking and feeling. Through new openings, or crevices, loosened moments, Chrusciel’s work makes its way past our major affective and cognitive registers: beyond approval or disapproval, beyond desire or disgust, we find it impossible to be either “for or against” what contraband elicits. We are rather suddenly “with” contraband, possessed, our boundaries having been crossed unnoticed. Performing its themes, the work of the smuggler is operative here, and our life as an either/or “border agent” is disarmed. With our guard down, a message that is not clearly heard or easily understood manages to get tangled up in our shirt or from within our protective garments: “The hoopoe’s wings beat under my blouse... The hoopoe is the dybbuk messenger chattering under my bra.” Chrusciel’s work gently challenges us in both form and content: her message is neither simple nor given, and her writing is nowhere heavy-handed. It is not for us to make clear what Chrusciel hides under her cloak, but to become unavoidably interested in what hides under our own. In other words, the work left to the reader is the stuff of poetry.

Ewa Chrusciel’s new book of poetry, contraband of hoopoe, asks its readers to do the work of not just reason or the sensuous but to engage their sensuous reason. Chrusciel is asking us to not only conceptualize or make real her vivid imagery in our mind’s eye, but to feel the bones and feathers of the hoopoe move against our skin—cross barriers—as reading becomes experience. In the movements between approbation and interrogation, we are left unsteady—opened up between thinking and feeling. Through new openings, or crevices, loosened moments, Chrusciel’s work makes its way past our major affective and cognitive registers: beyond approval or disapproval, beyond desire or disgust, we find it impossible to be either “for or against” what contraband elicits. We are rather suddenly “with” contraband, possessed, our boundaries having been crossed unnoticed. Performing its themes, the work of the smuggler is operative here, and our life as an either/or “border agent” is disarmed. With our guard down, a message that is not clearly heard or easily understood manages to get tangled up in our shirt or from within our protective garments: “The hoopoe’s wings beat under my blouse... The hoopoe is the dybbuk messenger chattering under my bra.” Chrusciel’s work gently challenges us in both form and content: her message is neither simple nor given, and her writing is nowhere heavy-handed. It is not for us to make clear what Chrusciel hides under her cloak, but to become unavoidably interested in what hides under our own. In other words, the work left to the reader is the stuff of poetry.

contraband unsettles our expectations of a recognizable or reasonable poetic experience. Formally, the pieces do not exhibit a pattern or follow a logic: some are sparse, some dense, some a list, others a short narrative, sometimes spoken by an “I,” at other times a “we,” “they,” “he,” “she,” sometimes “they” are properly named, some pieces are titled, others are not. In this way, Chrusciel creates a field of uncertainty: any possibility of tracing a strict chronology is thrown off, and the “mystery of feathers in feathers” (20) given room to expand. The contents of this scattered world are carried via the many different wings of contraband in vertical ascent over our now-physical, now-metaphysical borders. Even the landscape is in motion, can travel or come untethered; and every creature in these poems is given the work of dispersing, displacing and reformulating experience. This is experience as “sensuous reason:” fragments make their way into the forms of thought and feeling they themselves have loosened, arriving in what is now a shadow land prior to our capacity to judge, or tame them with our tastes:

But the hoopoe says: “So long as we do not die to ourselves, we shall never be free.” The hoopoe says: “For how can you remain the master of yourself if you follow your likes and dislikes?”

In contraband lies an uneven terrain of possibility where our desires are not already, and certainly not “always already,” completely articulated or occupied by past experience. This is our ascent, as we work up toward what might be new tastes or concepts. But for Chrusciel the world is shared, articulated by past experiences, and so the contents of contraband are also carried in vertical descent—down into the compacted world of ever-proliferating species generation:

My luggage goes through a “sausage scan.” Can an old sausage be born young again? The officer pulls me aside. The officer holds my sausage to the light. His babushka trophy. “It’s a sealed sausage.” I declare with pride. I’ve brought a new species. “But you declared: no meats,” the officer says. “Sealed Sausage is not a meat!” “Sealed sausage is a sealed sausage!” I say, as the guardian angels of my sealed sausage swarm under the investigation light.

The immigrant wants to cross the border into a space that is already named. Here, the name declares itself somehow already populated with people and objects: “The United States.” The immigrant brings something different, something not yet seen, concealed in the openings, something in the cavities of the body that upon passage beyond the border agent will become manifest—spoken, written, shared, enacted. The contents of contraband elicit a world of tree roots that tentacle horizontally, binding what might otherwise rise too far into thin air or fall too deeply into the muck. As Chrusciel writes, “Birches make underground passages. They make new universes.” We move from a foreign past to a past future, but the one is to the other only loosely twined.

What is carried across then in contraband can get tangled up together in both space and time, passing from those who have traveled to those who will, from the eastern block of Europe to Ellis Island, from a world of language and poetry lived in Polish to a voice now recorded in English. The writer here does take it with her, her history, their history, the immigrant’s history, but what is smuggled through is not destined to be locked down for safe keeping: it will instead speak in a differently-faceted voice to a differently-situated audience, a voice from amidst the lingering traces of communism to the kingdom of capitalism.

With its variety of form, content and spatial and temporal movement, contraband, offers up a world to be engaged with. We sew hummingbirds into our underwear and wonder about the necessity of the wrapping and hiding of anything that we hold dear, the necessity of carrying it concealed. But just there, with Chrusciel, we also feel the hummingbird and wonder how we might be moved to reveal it. How and under what circumstances are we moved to make our most creaturely desires known?

He wraps each hummingbird in cloth. They look like newborn babies. He sews each pouch into the inside of his underwear. He heads for the Rochambeau airport in Cayenne. What are the true desires in this disguise? The man did not know that hummingbirds calculate their own rates of return.

The movement then is twofold, reciprocated, even as we conceal our contraband (that which, if seen, may well be rejected, discarded like a beautiful Polish sausage thrown over the shoulder of the customs agent, into a trash brimming with confiscated meat), we feel the flutter of the hummingbird’s wings, and they irritate our skin. These hidden creatures are cordoned off but not contained underneath the cloth; they have their own drives, their own desires. The wings of the hummingbird want to be released, set off on some other calculated flight; but to be released, they must awaken our desire to be seen, noticed—and so they brush up against our most sensitive skin and bring us around to letting them go. Chrusciel is asking us to consider what lies external to us yet so proximal we feel it on the skin. She is asking what contraband attaches to our side like lively tumors as we look to travel across and through, between past and present, toward a future that chafes and confuses—asking us to let it appear, at least partially anyhow.

What will we need to cross the borders and boundaries with contraband? We don’t know exactly, but we probably need something that can sustain us when we arrive. We will certainly look to find those we recognize, kindred spirits, because the ability to leave behind familiar terrain requires ties that can re-bind without fully articulating a past and carrying it forward into a past future. contraband offers exactly those loosely bound moments, moments not colored by a hope simultaneously weak and powerful, but rather with the altered and elongated sensuous hope of the hoopoe.

The feathers of contraband are scratchy, desirous, disturbing even, but the view from this side is spectacular.

Lynarra Featherly is an experimental poet with a poet’s interest in critical theory. She received her BA from St. John’s College in Santa Fe, NM where she studied philosophy and the liberal arts and her MFA from UW Bothell’s MFA in Creative Writing and Poetics program. Her writing projects look to stitch together conceptual pieces from the tailings of German philosophy and Lacanian psychoanalysis—thinking and writing in an energized and figured field of dispersed, multiple and moderated or diminished agency. She is a co-founder and co-editor of Letter [r] Press, which publishes the journal small po[r]tions, as well as ephemera and chapbooks. She has work forthcoming from The Conversant.