Hope Wabuke is the author of the chapbooks The Leaving and Movement No.1: Trains. She is an assistant professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. A contributing editor for The Root, her work has also been published in The Guardian, Guernica, The North American Review, Salamander Literary Journal, Ruminate Literary Journal, African Voices Magazine, Literary Mama, Salon, Gawker, Ozy, Creative Nonfiction,The Hairpin, The Feminist Wire, The Daily Beast, Los Angeles Magazine, Ms. Magazine online and others. Hope has received awards and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Times Foundation, the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund for Women Writers, the Awesome Foundation, and the Voices of Our Nations (VONA) Arts Foundation.

Hope Wabuke is the author of the chapbooks The Leaving and Movement No.1: Trains. She is an assistant professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. A contributing editor for The Root, her work has also been published in The Guardian, Guernica, The North American Review, Salamander Literary Journal, Ruminate Literary Journal, African Voices Magazine, Literary Mama, Salon, Gawker, Ozy, Creative Nonfiction,The Hairpin, The Feminist Wire, The Daily Beast, Los Angeles Magazine, Ms. Magazine online and others. Hope has received awards and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Times Foundation, the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund for Women Writers, the Awesome Foundation, and the Voices of Our Nations (VONA) Arts Foundation.

Stacey Waite: Patricia Jabbeh Wesley describes your voice as one of “witness, inheritor, and emissary of history.” What does it mean to you to think of your work in these terms?

Hope Wabuke: Patricia was so wise and generous in the beautiful essay she wrote on my work. It is one thing to set out to write something; it is another thing for the reader to pick up on all the nuances of what you are doing and articulate that in such a profound, insightful way. I shouldn’t be surprised at Patricia’s reading of the text because she is such a brilliant poet and educator, but I think I was just so honored that she thought that I had achieved what I set out to do—and set my work in conversation at a level with writers whom I deeply admire and respect.

Patricia was talking specifically about my poetry collection The Body Family, which explores my family’s escape from Idi Amin’s Ugandan genocide and the aftermath of healing in America. In these poems, more than in anything else I have written, I did feel as if I was bearing witness to an experience, to a familial and cultural legacy that was absent in history. I had always felt an absence in my body to know my body family and our history, but my parents did not like to speak about it, understandably, because of the post-traumatic stress of living through and escaping a genocide. But it was not just prurient curiosity; I felt a responsibility to un-silence the silence so that our stories would not be lost.

So many of these poems grew from scraps of conversations with members of my family—I would focus on an image and the poem grew from there. A few came from dreams that I somehow tapped into and would speak to my parents about and they would swear up and down they had never told me those things—which is what led me to become very interested in the cultural memory that is passed down through the body. It also led me to be interested in inherited trauma—how DNA is changed through the experience of trauma, such as genocide, and then that changed DNA is passed down to the next generations. So inherited trauma is biological as well. I felt the presence of our stories needing to be told—both the stories of my own family line in that time of Amin’s genocide, but also what it meant to our community, our tribe, our Ugandan people. I do not claim to speak for everyone; I cannot. There is no single story, and there is an extreme danger in assuming so, as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie tells. I simply tried to tell what narratives I could in poetry to the best of my ability.

The poems in this collection didn’t feel as if I was making them up, but discovering a truth—expanding an image into meaning, being a vehicle for the many voices of the experience to be un-silenced. I felt that I could not walk around with all this feeling and memory in my body. I had to bear witness to it. I had to honor it. And now that that book is finished I feel the weight of the urgency of the need to tell these stories has been lifted.

I am interested in the act of healing from violence in the refugee immigrant community. There is so much silence, so much trauma in our communities—our families and our bodies. We have been taught not to speak about these things because they are too painful. The genocide. The torture, the death. The names of friends and family disappeared or left behind. What was done to be able to escape.

I think it is important to look—to speak. To bear witness. To un-silence the silence and heal; to not repeat this legacy in our families—towards others, towards ourselves.

SW: What are your greatest hopes for what your poems might make possible in the world—perhaps both in the literary world and the “real” world itself?

HW: My hope is that my own journey will speak to others who have lived through the refugee experience to find healing, and that those who have not lived this experience will be able to empathize and understand what was formerly alien to their existence. I also hope that this work can do a little part in advocating that our society can become a safer place, free from such terror and violence.

SW: How do you think about the relationship between narrative and fracture?

HW: There is something about linear narratives that privileges a certain kind of Eurocentric patriarchal view of the world. If you look at the way the linear narrative of history is taught, most begin with the stories of how Europeans began to interact—usually violently—with other cultures in other spaces. The myth of Christopher Columbus “discovering” America is what begins the story of the First Nations people, rather than the rich history of the First Nations people that existed here before his arrival. The same is true in history and literature written about Africa. Just yesterday, my aunt and I were talking about the history of Uganda—the Bantu speaking peoples and how Masaba split into a separate tribe, which is the tribe my father is from. And this was centuries before the British came to Uganda. But the history and literature books written by non-Africans start with the colonization of Uganda by the British, with the colonization of Africa by Europeans.

And because of the insidious and powerful perpetuation of this worldview, there is a value layered onto having a lengthy history, onto having a lengthy timeline—and the written documents to show for it. I think silencing the histories of our cultures creates a very powerful political statement about the value of whose actions, whose story matters.

Dr. Michelle Wright, when speaking about this idea of privilege and the linear timeline and blackness in America and Europe has coined a term called “epiphenomenal time,” which is fascinating and, as an academic text, expounds more fully upon this idea than I can as a poet here in this space. But the general idea is an interrogation of linearity, an interrogation of “starting points” and the idea that time is circular and that is valid to select other starting points than the ones privileged by the Eurocentric patriarchal viewpoint—and then move backwards and forwards from that starting point in a circular, non-linear timeline. I think that this work exposes so much about conscious and hidden biases of culture, progress, modernity, privilege, and advancement. I think this changes so much.

But even before thinking and reading through these things as a scholar, I always unconsciously felt, as a writer and thinker, that the fracture was the only authentic way to represent narrative. All narratives are fractured; we do not continuously go from A-Z; we choose moments to show between A-Z, and among those moments, we choose which to express in full, and which to elide. I felt a necessity to draw attention to this artifice and utilize the fracture as authentic representation in terms of structural reliability.

Given my own personal background, I felt like I was the fracture—the first generation immigrant exiled snippet living in absence and silence of my homeland and connection to our historical narrative therein—and that anything I wrote about that fractured experience would also have to privilege the fracture. I think this is something that poets also move more organically towards; we write these bursts of deeply imagistic, meaningful moments. It is that sustained poem that is the thing; less important is the linear order of the poems themselves; more important is the emotional truth of the arc of the individual poem, the arc of the whole poetry collection.

SW: When people who are not poets ask you, “what do you write about,” what do you say?

HW: I just finished writing my poetry collection The Body Family, which explores my family’s escape from Idi Amin’s Ugandan genocide in 1976 and the aftermath of healing in America. Not everything I write is specifically about Africa, but I begin there. However, I think that the idea of looking and bearing witness—the themes of identity, trauma, power, masculinity, family, womanhood, motherhood, blackness, and cultural memory are embedded within all of my work.

To quote the great Toni Morrison, “if there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” When I was a young black immigrant girl from Uganda growing up in southern California obsessed with discovering my African identity, the ancient Greeks and Romans, all things sci-fi and fantasy, feminism, science, and classical music, I could not find any books that held two or more of my intersections of self. I identified with the narratives I found in literature written by black Americans—Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, James Baldwin, Nikki Giovanni—gave me a way to see parts of myself on the page that I am deeply grateful for. And I identified with some of the narratives I found written by other nonblack people of color or other marginalized individuals: Sandra Cisneros, Junot Díaz, Jhumpa Lahiri, and Michael Cunningham for example. But within the classic sci-fi/fantasy literature, or the mainstream literature we read in school, I never saw myself. The characters and way of storytelling were all about and written for straight white men. There came a moment when, inevitably sometime into a pretty awesome story, you would be hit with a moment so shockingly sexist, so shockingly racist, that there was no way around it. Like Claudia Rankine writes in Citizen, you are constantly negotiating whether you will stop and say something, or if you will drive around that moment as if you haven’t experienced it a million times before. Every book we read in English class from elementary to high school, I would be the one person who would point out the racism or sexism or intersection of both. It became exhausting. And I loved reading. It was what I did all hours of the day and night.

So I have two answers to this question, one long, one short. The long answer is that I write the stories and poems I always wished I could have read when I was a child. Stories that explore the experience of what it is to that little immigrant black girl being confronted with stereotypes, racism, and prejudice. I write about what it is to inhabit that liminal space of the experience of two or more cultures. I write about exile, about power and systems of power, about the body, about family, motherhood, and cultural memory. I write about the need to interrogate what we value as a society and why—and to create a space to value people and ideas that have traditionally been marginalized and oppressed. I write about what it is to bear witness to trauma and violence and the effect of inherited trauma. I write about the importance of seeing people as people and not as expendable or of less value because of their nation of birth or color of skin or gender or who they love or any intersection of all of these. I write blackness. I write about women. I write about children. I write about love and faith and empathy and the importance of these three things in moving forward into any kind of just world that values life, rather than violence. Some people would call this writing about race, gender, class, and feminism. Some people would call it political. I say that everything is political: what you choose to look at and what you choose to ignore is at its very core a political act.

The second answer is simpler and shorter: I write about identity, relationships and love—all the awful and wonderful things that happen in the name of all three.

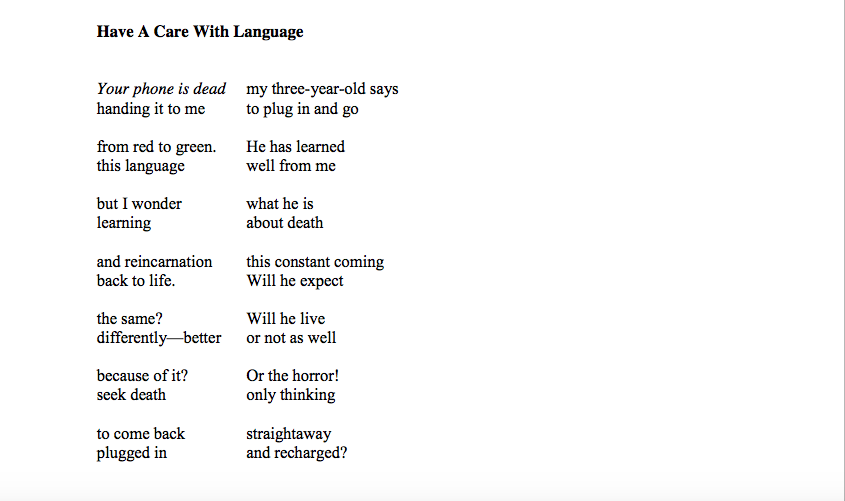

SW: In “Have a Care with Language,” a poem featured here, you talk about your son and in a way the poem is a reflection on his possible perceptions of how narrative unfolds through language. How does watching language unfurl in a young person shape your own understanding of language, line, and poetry?

HW: As someone who thinks deeply about language, it is incredibly inspiring and incredibly humbling to see and hear the formation of language through the mind of a young child. Children are brilliant geniuses with language. Every day they say so many profound statements and gorgeous, imagistic phrases that, if we pause and listen, we can hear that they are poems.

My son is four and he is very verbal. He writes these beautiful, resonant poems—replete with the kind of clarity and metaphors that so many of us poets aspire to. But he doesn’t know what he is doing on a technical or craft level, I don’t think. Maybe he does—maybe he is already analyzing from the many books we read what works and what doesn’t work as he forms his own sentences and meaning. But what I see is that he is simply trying to communicate as clearly and as simply as possible what he sees—which creates a kind of musical grace in the language.

An early writing teacher of mine, sensing my potential at times to ascend into elaborate structures of fluff—inspired I suppose with my obsession at the time with Dickens and other Victorians—said to “keep it simple and write exactly what you are trying to say.” This is what I see my son doing: saying, very simply, what he is trying to say. And the poetry lives there, breathing out organically. But the beauty, the magic, I feel, lies in the way children connect things in their minds—the openness and wonder and possibility that has not yet been layered over with all the many things in this world that try to destroy the imagination and make one conform to one way of thinking. So if my son is thinking about joy—the connections in his growing brain of what he connects joy to—both physical and abstract objects—how he can use his still unfossilized language to move between the synapses firing between his brain—how he is still discovering language and sees connections among words based on sounds or rhyme or current word associations or a million other things we have forgotten that he is still discovering for the first time is astounding.

SW: Many of your poems reflect on and revise biblical narratives—how do you understanding the role of these narratives in your own work?

HW: When I was younger, I turned away from Christianity—not just because the severe sexism I experienced in my family firsthand that was justified by this religion, but also the larger systematic violence that had been done by people in God’s name—the brutal European colonization of Africa and other parts of the world, the horrors of American slavery, and other forms of racism, sexism, war, and genocide throughout history. It was only after I became a mother that I understood the importance of a spiritual belief system—of meaning larger than oneself—of the sacred. And that my concept of God could be different that the one I was raised with. A lot of my work reckons with and interrogates Biblical narratives—whether it be to reclaim my relationship with God outside of a religious tradition burdened with racism, sexism, homophobia, and sexual assault, or simply to look closer at something that has impacted our world for so long in such a powerful way and try to understand it a little bit more.

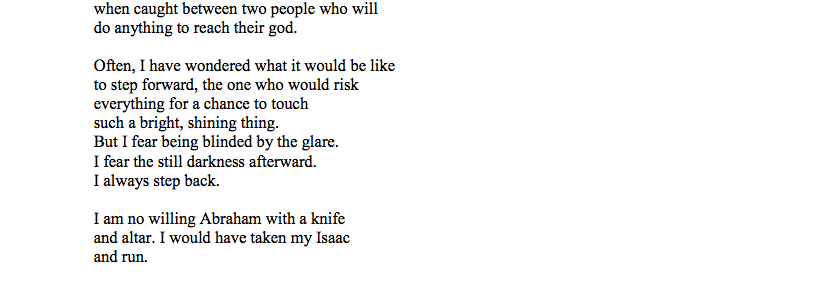

SW: In “That Bright, Shining Thing,” you talk about “the quiet giving way” of a speaker who notices a pattern in her own life reflected in this moment. Do you think of your poems as a resistance to this quiet, or a kind of transformation of it?

HW: That is a very perceptive reading of this poem. If I am honest, I see it as both. I think that there is usefulness in resistance for the sake of resistance. But I am always pushing forward. I like to think of the idea of creation through resistance, creation through disruption. I think that type of creation is a type of change and growth; it is ultimately, a form of transformation. In order to change something—change anything—we cannot rest with the destruction of what was; we must rebuild something better. I think this is where the act of bearing witness that we spoke about earlier and the Morrison blessing to create what has been absent unify. In my mind, I see the image of the phoenix rising from the ashes. For so many people from marginalized identities, this is often the work that must be done to make any traditional space or belief system safe for us.

I was thinking, also, about all these terrible things that happen in the Bible–many of them requested by God. Something I never understood was how God asked Abraham to kill his only child Isaac–this child that Abraham and Sarah had prayed to conceive for decades. God told Abraham to take Isaac to an altar and stab him to death with a knife as a sacrifice instead of the animals that were sacrificed routinely throughout the Old Testament.

This act–this story–seemed inhumane and horrific to me as a child, and it seems even more so now that I am a mother. In church when I was younger, the pastor would explain that this moment was not about the act of possible murder of an innocent child by his father, but about being tested by God–about the need to have faith and do whatever God tells you, no matter what. That if Abraham just trusted God and did what God said, everything would be alright. I think by the time I heard this Bible story as a seven or eight year old I had enough trust issues that, if I was in Abraham’s position, I knew I could not have taken Isaac to the altar and gone through with the act, trusting that God would say “Just kidding, this was a test, you do not have to kill Isaac now.” I wondered at what kind of God would ask this of a parent. I wondered at the trauma Isaac experienced. I wondered at how this changed Isaac and Abraham’s relationship. I wondered at how Sarah, Abraham’s wife, felt about all this. I wondered at the idea of sacrificing everything because God tells you to, of doing the unthinkable because God tells you too, no matter what. I wondered at all the people who have committed terrible, heinous crimes and then said God or some other voice told them too–and who are then sometimes determined to be mentally ill. I wondered at how the interpretation of what is the voice of God and what is insanity changes depending upon time period.

But mostly I realized how much this story still affects me to this day; it is one of a group of stories in the Bible that, no matter how I try to look at them, I cannot understand them. I could never do such a thing. And that line that I could never cross–this thing that this story says one must be prepared to do if God asks–is what “That Bright, Shining Thing” reckons with.

Two Poems by Hope Wabuke

Stacey Waite is Assistant Professor of English at the University of Nebraska—Lincoln. Stacey’s poetry collections are: Choke (winner of the 2004 Frank O’Hara Prize), Love Poem to Androgyny (winner of the 2006 Main Street Rag Chapbook Competition), the lake has no saint (winner of the 2008 Snowbound Prize from Tupelo Press), and Butch Geography (Tupelo Press, 2013). Individual poems have been published in The Cream City Review, Bloom, and Black Warrior Review, and other honors include: the Elizabeth Baranger Excellence in Teaching Award, three Pushcart Prize nominations, and a National Society of Arts & Letters Poetry Prize. Stacey is also the co-host of Air Schooner, a weekly podcast show produced by Prairie Schooner.