FLOW

“And you really live by the river? What a jolly life!”

“By it and with it and on it and in it,” said the Rat. “It’s brother and sister to me, and aunts, and company, and food and drink, and (naturally) washing. It’s my world, and I don’t want any other. What it hasn’t got is not worth having, and what it doesn’t know is not worth knowing. Lord! the times we’ve had together!….”

– Kenneth Graham, Wind in the Willows

I live surrounded by a language which is not my mother tongue. It has its own rhythm, its own music and gurgle and bubbling laughter, its own icy formalities, its own intonation and pitch. Replete with false cognates, it is sometimes duplicitous, sometimes uproarious. It has its own history and archaeology of archaic usage. Despite having read many in translation, I am just beginning to read some of that language’s contemporary writers in their original language—slowly—and I am delighting in their pyrotechnics. These tales sparkle; they are fire and glitter.

But I am thinking also of my mother tongue, with its Germanic roots, its soaking up of words, phrases, even idioms of every language with which it, as archaic English would put it, has had congress. Like water, it is agile and slippery; it fills every hollow, flows from subject verb to object, offers enormous choices of vocabulary; its eddies fill up with expletives, asides and modifying phrases.

The River Road

I face a huge Steelcase file cabinet, shipped out of country to my present location; and it is, alas, full of detritus, most destined to become the cremains of my several incarnations—old CVs, drafts that I hope no one ever reads, job applications and unfinished proposals, old news clippings, clips of my old dance and theatre reviews, when I had a byline in a regional arts paper, good god! old boarding passes, and aha! drafts I do want to keep. Most serve to start the nightly fire in my fireplace; but I try to be careful and go slowly through its contents.

Like Mole. Spring cleaning.

I grew up in Delaware, as did one of my dearest, also literary, friends, D. He is now writing about a difficult but indelible part of his childhood, when his extended family left the urban northern New Castle county of our tiny state and tried to make a go of farming in one of its most beautiful backwaters—along, not the famous route 32 Pennsylvania byway that rims the Delaware River, but the lesser known, route 9 River Road, also near the Delaware, that goes past Taylor’s Bridge and its Blackbird Creek, crosses the Chesapeake-Delaware Canal into Kent County, one of the lower two counties of the state, and what we grew up calling “Slower Delaware.” It is a flat, marshy area crisscrossed with little creeks and, in bygone days, variously colonized by Swedes, Dutch, then English-speaking settlers. The Dutch called these little rivers, “kills”; and so you find startling names like, as bastardized by the British, the “Whorekill (the Hoorn Kill),” the “Murder Kill” rivers. Who knows what the Swedes called them, or the original inhabitants; its Lenni-Lenape Indians were removed, one way or another; and survivors joined the infamous Trail of Tears.

I grew up in Delaware, as did one of my dearest, also literary, friends, D. He is now writing about a difficult but indelible part of his childhood, when his extended family left the urban northern New Castle county of our tiny state and tried to make a go of farming in one of its most beautiful backwaters—along, not the famous route 32 Pennsylvania byway that rims the Delaware River, but the lesser known, route 9 River Road, also near the Delaware, that goes past Taylor’s Bridge and its Blackbird Creek, crosses the Chesapeake-Delaware Canal into Kent County, one of the lower two counties of the state, and what we grew up calling “Slower Delaware.” It is a flat, marshy area crisscrossed with little creeks and, in bygone days, variously colonized by Swedes, Dutch, then English-speaking settlers. The Dutch called these little rivers, “kills”; and so you find startling names like, as bastardized by the British, the “Whorekill (the Hoorn Kill),” the “Murder Kill” rivers. Who knows what the Swedes called them, or the original inhabitants; its Lenni-Lenape Indians were removed, one way or another; and survivors joined the infamous Trail of Tears.

A long time ago D. and I had planned to write a series of articles about the River Road; and I found these notes among scribblings on the area’s colonial history, it’s geography, our contacts, etc. They begin with me taking a picture of D., posing 100 yards from a refinery, by a blue and gold historical marker, with his maroon cap set at a cheerful angle. I did it to document the beginning of our collaboration:

“You mean this is the beginning of the River Road?” I asked. I had in mind a mist-swathed path with an occasional lone trapper poling a flatboat through the adjacent waterway, something like a George Catlin painting of the old frontier. Anything but an industrial parking lot.

“You’ll see,” he said.

As the number of our forays along the River Road increased, “seeing,” in that sense, became an obsession. I observed the delicate task of balancing human needs with long term concerns that that very specialized environment not be exhausted by human activity; and, through D.’s reminiscences and the people we encountered, I observed the effect of this mutual balancing act upon the social fabric of this most haunting of landscapes.

More than once I felt as though, native Delawareans though we both were, that I was like Mole in The Wind and the Willows and D. was the Water Rat.

From fictitious letters to a non-fictional friend:

Dear Chica,

Remember when I visited Montevideo, Uruguay, quite a few years ago, and interviewed Eduardo Galeano? Yes, the Galeano who wrote that book, that courtesy present to Obama from the late Cesar Chavez: Venas Abiertas de Latinoamerica (Open Veins of Latin America.) Venas Abiertas,  I still believe, is a necessary text for anyone wanting to understand the predatory, rarely friendly, relationship between Anglo north and Hispanophone and Lusophone south. More on that in another conversation.

I still believe, is a necessary text for anyone wanting to understand the predatory, rarely friendly, relationship between Anglo north and Hispanophone and Lusophone south. More on that in another conversation.

I had come to visit N., mi hijo, in Buenos Aires, so all I had to do was take a puddle jumper across the Rio Plata, the Silver River, to get to Montevideo. N. and I were yet to visit the Iguazu Falls, whose already augmented Parana River, second only to the Amazon in size, hurled over huge cliffs between Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil, gathered up speed as the Uruguay River poured into it, flowed into and became the Rio Plata, and flung itself into the sea.

Rather than a graceful arc, the plane lurched; and between the two countries and the two cities, looking down, the river seemed frightfully wide, gleaming like a service tray, and deceptively still. Its banks were flat as pussy’s foot on the Uruguayan side; and only as the taxi approached the city did we go upwards on Montevideo’s one and only hill. I cannot remember that shoreline without also remembering the old movie, De Eso No Se Habla, (Let’s Not Talk about It.) De Eso was Argentine director, Maria Luisa Bemberg’s, last film, and also one of the last films Marcello Mastroianni acted in. All about an aging roué who fell in love with a dwarf, it opened with shots of Colonia, Uruguay, along the Rio Plata.

But we landed outside of Montevideo, not Colonia. There, finding my way to Galeano’s house, I passed through neighborhoods where, during the time of the deposed dictatorship, I was sure, one half of the population ratted on the other half—or perhaps the proportions were, on the ratters’ side, less gargantuan as the ranks of the silent proportionately swelled, fearful and oh-so-mum before the spectacle of civil cruelty. They were even more fearful, I suspect, of those who bravely opposed it. In 1985, when Galeano returned from exile in Spain where he had fled, one jump ahead of the agents of Argentina’s “Dirty War”1—and that after he had fled Uruguay’s similarly inclined generales in his own country—I wondered what kind of welcome he had had. For, on the surface, like the aerial view of the Rio Plata, everything looked quite calm and unruffled. Nothing, nada, at the time of my visit seemed dangerous, nothing was out of the ordinary, let alone out of whack. Hannah Arendt’s famous phrase, “the banality of evil,” comes to mind.

But we landed outside of Montevideo, not Colonia. There, finding my way to Galeano’s house, I passed through neighborhoods where, during the time of the deposed dictatorship, I was sure, one half of the population ratted on the other half—or perhaps the proportions were, on the ratters’ side, less gargantuan as the ranks of the silent proportionately swelled, fearful and oh-so-mum before the spectacle of civil cruelty. They were even more fearful, I suspect, of those who bravely opposed it. In 1985, when Galeano returned from exile in Spain where he had fled, one jump ahead of the agents of Argentina’s “Dirty War”1—and that after he had fled Uruguay’s similarly inclined generales in his own country—I wondered what kind of welcome he had had. For, on the surface, like the aerial view of the Rio Plata, everything looked quite calm and unruffled. Nothing, nada, at the time of my visit seemed dangerous, nothing was out of the ordinary, let alone out of whack. Hannah Arendt’s famous phrase, “the banality of evil,” comes to mind.

Politely, Galeano asked how my flight was: I confessed to being a fearful flyer, reiterating how an acquaintance assuaged his mother’s flying anxiety by comparing chop to riding the waves in a sailboat. In response, Galeano compared his plane ride back to Uruguay, in the company of his mother, to a sea voyage; and when there was turbulence, he told his mother, it was merely a few swells of the ocean or the tides shifting at the mouth of a great river.

Crossing that river, I entered a writer’s world. At the time, Galeano was on death watch: a friend clung to life, resisting the next step with its one more river to cross; and so a worn Galeano spoke in his native Spanish, while I fired questions away in my native English. For his current project, Palabras Andantes (translated as Walking Words) he said, he had begun to work with a Brazilian artist, Jorge Borges2 whom he found illustrating historias de cordel (stories on a string) in the markets of northeast Brazil, “lo mas pobre, pero lo mas rica” in terms of its culture, said Galeano. Historias de cordel, he explained, are hand sewn booklets filled with local news, gossip, astrological predictions, short stories, jingles, poems, politics, lord knows what else, and illustrated with handmade block prints.

At that juncture, Galeano turned and took several of these little booklets from a large stack behind him and handed them to me. They smelled of tobacco, of the sweat of their readers and makers, of the coffee someone had drunk, of the cheap vino tinto someone had spilled…

Back then, Galeano spoke of the short distilled paragraphs he worked with as “ventanas“—windows—through which one glimpsed a moment of life, an idea, a phantasm. Though I have looked all over, I can’t find my favorite example of these ventanas, in English or in Spanish. However, in the one I am thinking of, he describes a friend, imprisoned by the generales of the dictatorship. Thin, worn by torture and starvation, the friend sees a broom, leaning against the wall. Slowly, in rhythm and in majesty, he takes it as a partner and executes the sensuous steps of a tango.

Back then, Galeano spoke of the short distilled paragraphs he worked with as “ventanas“—windows—through which one glimpsed a moment of life, an idea, a phantasm. Though I have looked all over, I can’t find my favorite example of these ventanas, in English or in Spanish. However, in the one I am thinking of, he describes a friend, imprisoned by the generales of the dictatorship. Thin, worn by torture and starvation, the friend sees a broom, leaning against the wall. Slowly, in rhythm and in majesty, he takes it as a partner and executes the sensuous steps of a tango.

Dear C.,

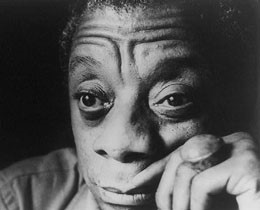

Far away from the monstrous rivers of South America or my humble Delaware marshes, in your eagle’s eyrie in the city—though near a great river, too—you have recommended reading James Baldwin. It has been a while. I remember assigning him to a student I tutored, way back when, at the University of Delaware. I fear the student was a twit; worse still, he was a racist twit whose ignorance of English writing was outdone only by his ignorance of the human condition. I handed him Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time and told him to read it, told him that this was an example of the best contemporary English writing I knew. He turned the book over and saw the photo of the author. Ha! I thought as I watched his face fall, swallow that. To his credit he did read it, his writing improved ever so slightly, though I will never know if Baldwin made any difference to him.

In his 1962 essay, “The Creative Process,” Baldwin talks about the difficult choice, the necessity, the artist’s choice, which most presumptively “normal” people avoid, the choice to be alone. Worse still, he talks about the artist’s role in illuminating the wilderness in him/herself so that “we”—not merely the tiny ego of one—contribute to making “the world a more human [I might add an ‘e’ here] dwelling place.” What a masterful writer Baldwin was, even when he came up with egg on his face in some of his lesser work.

In his 1962 essay, “The Creative Process,” Baldwin talks about the difficult choice, the necessity, the artist’s choice, which most presumptively “normal” people avoid, the choice to be alone. Worse still, he talks about the artist’s role in illuminating the wilderness in him/herself so that “we”—not merely the tiny ego of one—contribute to making “the world a more human [I might add an ‘e’ here] dwelling place.” What a masterful writer Baldwin was, even when he came up with egg on his face in some of his lesser work.

I am also struck by the book you recommended, The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings, by Baldwin, and am reading the various essays. The editor, Randall Kenan, introduces Baldwin with a praise song to his mastery of language and a list of writers—Faulkner, Woolf, etc.—who, as did James Baldwin, especially in his essays, “dared put so much demand on the language” :

Death-defying sentences. Lush, romantic sentences. Sentences that dared to swallow the whole world. These writers were undaunted by outrageous complexity, clauses, dependent and independent, modified, interrupted, periodic. They trust in the force of their meaning and their music (and the rules of good grammar) to carry the feat….

And here’s the kicker, as far as I’m concerned: “Reading a Baldwin sentence can feel like recreating thought itself. One has to take hands off the rudder and trust the river of thought as it flows.”

Aha!

You start with a sentence. The next one emerges from that one. If you are careful—and lucky—the next thought joins with the main current of your idea; tributaries converge; your words eddy around an image… Is this writing as navigation or hydrology; reading, as giving in to the river? Flow. Is there a trick to it? No. Is it easy? Whether literature or journalism, it isn’t; and I refer you to what sportswriter Walter Wellesley (aka “Red Smith”) putatively quipped —all you have to do is sit down in front of the typewriter and open a vein. This goes beyond the extended metaphor of a river’s inexorable flow that authors as varied as the German romantic, Hermann Hesse, or the Guyanese experimental writer, Wilson Harris, have used to structure whole novels; or Nicaraguense Giaconda Belli has used to set the stage in Waslala, her novel of Centromerica’s dim future, with its image of a community along the banks of an unnamed river, thrashing its way like the great Quetzalcoatl towards open waters. What I am really saying is that rivers manifest movement; and writers’ language must both connect and move, capture a reader unawares in a sensuous current of words that, as Kenan points out about Baldwin’s, do not show off, but communicate the thought, the rush of narrative, the idea, the image—the metaphor—at hand.

At the same time, I cannot forget those humble historias de cordel and their inspired ventanas, the glimpses into both the ridiculous and the sublime of human life. Their existence is an alternative to the received wisdom that the visual, that cinema alone, informs those short pieces that flash by or fade without transitions, that build layer upon layer until the whole piece comes to an end and we, the audience or the reader, “get it.” Neither Hollywood’s slick, increasingly bankrupt productions, nor the e-readers more and more of us use, let the audience or the reader catch the protagonist’s scent, smell the story, leap up after something—a paper towel? a washcloth?—to mop up that slosh of tinta the reader before them just spilled in their excitement over the printed page. Neither lets the reader dance a tango with a broom that does not turn into a Prince Charming, but at best a weary human being who nonetheless struggles to keep hope alive. We ignore the sensuous at our peril.

When I was living in Istanbul, I used to sit in front of my study window at night, in my rocking chair, cut the lights, and watch huge oil tankers sneak up the Bosphorus, one by one, a dim warning light blinking above each bow. The straits were so dangerous, all nighttime traffic was supposed to cease (but it didn’t): oil fires burn for ages, and ever since the Byzantines’ secret weapon, “Greek fire,” a conflagration on the Bosphorus has been a fearful thing. Navigators warn us that the Bosphorus has two currents, one traveling over the top of the other, one going towards the Marmara and, eventually, the Dardanelles; the other, towards Kara Deniz, the Black Sea. Those waters can take you down in a second.

Memory is a natural process that flows backwards, forwards, and ignores sequence; but we cannot communicate a single event in that collection of past ones to another human being except in sequence, from beginning to middle to end. And, no, this is not easy.

Nonetheless, as writers, our words must flow, create a river of thought; and as readers, tantrum all we might about not getting all the information at once before the journey begins, we must relinquish control and learn how to let that river take us wherever it wants us to go.

1 For readers who may not know, in 1976 a right-wing military coup took place in Argentina and held sway until 1983. This government tortured, killed and “disappeared” thousands of its own citizens on the flimsiest charges—anyone perceived as politically left, whether merely attending a single labor union meeting or being true activist. When I visited Buenos Aires La Ricoleta, an otherwise upper class cemetery, I will never forget coming upon a huge wall, clearly made to accommodate drawersful of the ashes of the deceased, and among those properly placed, seeing photos of young people with no date of death. They were among the desaparicidos.

2 pronounced differently in Portuguese and not to be confused with the Argentine writer, Jorge Borges.