Two boys are practice-dancing shirtless

on the lawn. A bicycle is chained to a rack for bikes.

People fill the quad like they know what they’re doing.

One guy’s in the middle of it all with a video camera.

He’s turning in circles like a narrator.

I raise my hand and he raises his almost

like a flinch at first. He thinks he knows me. He doesn’t.

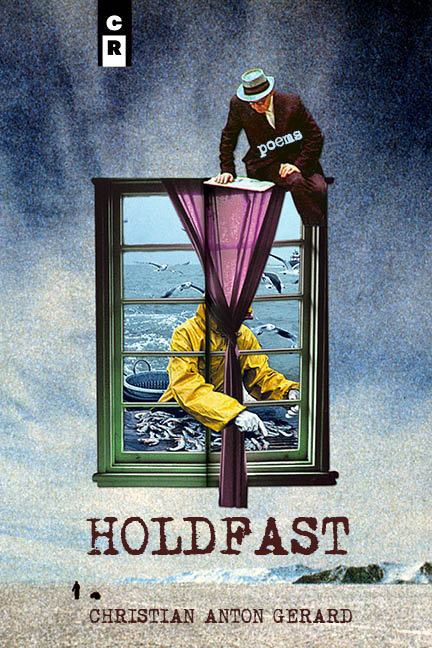

These are the first seven lines of Christian Anton Gerard’s latest collection, Holdfast (C&R Press, 2017). In dense, circuitous, always heartfelt, and often humorous poems that celebrate a wide-ranging poetic heritage, Gerard undertakes an unrelenting interrogation of self. In doing so, he creates both an experience of, and a defense of, making. He stakes a claim for the poem and the life forever under construction, and possibly for the poem as the life forever under construction: “I keep reading / all these poems about poems and poets / trying to become what I read... .”

Let’s start with the speaker of these poems. Let him be called the poet-speaker, for in Holdfast, Gerard leaves Marvin Bell’s “I”— as in: “The I in the poem is not [the poet] but someone who knows a lot about [him]”—far behind in that aging poetics that has always found confessionalism distasteful, and relentlessly embraces himself as poet and speaker: “Christian was like that blue room”; “Where are you, Christian?”; “Christian’s not a patient man.” Christian Anton Gerard is literally all over this book, with no less than fourteen poems that use the poet-speaker’s full name in the title, and many more that—as in the quoted lines above—address the poet-speaker directly. This is how we know we are reading a project of selving, of the poet-speaker not finding, but making, himself. This is how we know that the poet-speaker “is turning in circles like a narrator.”

And turn in circles he does. The book begins with a scene-setting, a declaration of the quest at hand: “I am Spenser’s Calidore...”—the knight who sets out to slay the Blatant Beast, but gets distracted, and infamously interrupts other characters, throughout The Fairie Queen. Christian Anton Gerard is always getting distracted, always interrupting himself. Sometimes with another poem, another poet, claiming wide-ranging literary heritages from Shakespeare to Robert Creeley, from Rilke to Adrienne Rich. Sometimes by yet another attempt to know, to become: “Christian Anton Gerard’s trying / to pin down a self... .” While trying, he narrates everyday moments of friendship, fatherhood, householding, music, love, addiction, and recovery. These themes and moments become both the materials and the tools by which the selving is accomplished: “I’m sure / if I can build the Adirondack-style bistro set I’ve promised my wife / for our already-passed anniversary // ...I’ll be the man who ran against the wind and won.”

Part of the power of this book is its obsessiveness, its relentlessness. This comes through in both the content and the form of the book, as the poet-speaker returns again and again to the same themes, scenes, and formal methods. In “Confession of the Alcoholic Poet Who Brought Books into a Public Restroom,” in which he addresses (amongst others) the poet Gerald Stern, Christian Anton Gerard’s formal choices—fast-flying questions packed into dense stanzas, recombinant repetition of words, phrases, and sounds—enact the poet-speaker’s earnest anxiety:

Gerald, were you comfortable

sitting between Rome and New York, ancient

and modern, all the noises? Did you know

Liam Rector? Did you get a feeling

of discomfort, pressure? Did you feel that

pressure to be a good person? Poet?

Did you wait for the feeling

and then when it [did come] do its bidding?

Or, like him, on a very good day,

did you not much give a shit about that?

I’m in a toilet-stall trying to follow

the scrawled connected voices, but

I can’t stand up, burst into the next

stall to see where the conversation goes.

I’m stuck here crouched between knowing

and not, between urges making me

animal, and this feeling,

this human pressure.

But this is a particular type of obsessive text—of not an elliptical obsessiveness that exists only in the writer’s consciousness, but of a narrated obsessiveness woven through daily life: first I did this, then I did that; first I thought this, then I thought that. The result is an obsessiveness that feels dangerously near, one that could close in on our own ordinary days at any moment. In this, Christian Anton Gerard creates a not-quite-comfortable intimacy with the reader and engages her in the project of the book.

If the first section of the book is a scene-setting, the second section moves (again, obsessively; I will keep using that word) into a defense of making. Here is “Defense of Poetry; or The Poet Explaining Himself,” a not-quite-ars-poetica; a not-quite-sonnet that takes shape mainly in ten syllables per line but eschews the turn that would occur in the twelfth line of a classical sonnet. Gerard stops short at eleven:

I’d forgotten the moon last night would rise

like most other nights because nights come, dark

and droning on for hours while I’m scared

I’ve forgotten how to make a sentence or

because the moon’s poetry’s bright cliché.

When I tell someone I’m a poet

they say, I don’t know anything about poems—

Take the moon’s picture tonight, I should say,

show it to a stranger, ask if they see

grief, or grievance, joy. Ask if we sometimes

gamble for the impossible because.

The poem ends on a phrase that could be the beginning of the next thought, or even a fragment, but is made, last-minute, into a noun by its terminal punctuation. That is, “the impossible because” could continue into a reason why we sometimes gamble for the impossible, or it could end without punctuation, falling softly into silence. Instead, in this stunted sonnet, it becomes the goal of the poem and of poetry: the impossible because.

The book’s final section settles, albeit uneasily, into a more restful tone with the appearance of Her, the object of Christian Anton Gerard’s love and longing, the source of whatever peace he is able to find, the complement to the self he is making. The poems still obsess, but more gently, with softer textures and shorter lines, as in “Poem with Pursed Lips”:

Sure, Wallace Stevens, a dwelling’s made

from air, and in the evening,

and it can be enough. Should be.

But there’s more—She is the evening,

putting on the garments stitched

from air coarse and fine and

the stuff of breath—making a man...

The poet-speaker is still making himself, but now he has help: “I walk now / a skeleton re-wrought because of one woman.” Yes, it’s a Romantic (capital ‘R’) notion that love can transform, can help us along in our selving. Yes, it risks sentimentality. But it is also true, and Christian Anton Gerard does not shy away from love in these poems, but enters into it like a supplicant, or maybe an apprentice.

If it’s not clear already, I’ll say it plain: This is the same posture in which he enters into one poem, and all of poetry: as supplicant, as apprentice. The result is that, taken as a whole, Holdfast transcends its own project—the selving of Christian Anton Gerard—to become an homage to poems, poets, and poetry. Poets are given to saying beautiful, impossible things like, “The book itself is the final poem,” as Robert Frost reportedly said. As skeptical as I tend to be of beautiful, impossible statements about poetry (or anything else), Frost’s quip holds true for Holdfast.

The state of the world and our nation has led to calls for poetry of protest and resistance, and has some people questioning the value of what I’ll call the art of interiority: art which takes no public stance beyond its existence; art which embraces the mind, the soul, the self, the process of selving. As the world burns, as the exiled hunger and roam, as the president tweets us ever closer to oblivion, is there room for the art of interiority? I say yes.

And I am not alone. In August, I listened to the poet, writer, and critic Rigoberto Gonzáles talk about the role of creative work as both node and mode of activism and resistance. He argued that cultural labor is political labor and is just as important as marching in the street and calling elected officials. Writing—regardless of what’s written—is an act of resistance, Gonzáles said. He also said, “By writing, I put a handle on the world so I can grasp it.”

A handle, a firm grip, a holdfast. This is what Christian Anton Gerard has given us in this collection. Grasp it. Hold on. Make, and be made, and defend the making, and the made thing:

Your poem’s whole life before and behind it.

Your poem will be standing there holding her, and your heart

will jump inside your chest’s pocket, your fingers on her spine.

The tears will be quiet, and you,

you poem you, where everything happens so fast,

you’ll say, I want to read you this story I love.

Molly Spencer’s poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Copper Nickel, Georgia Review, The Missouri Review online, Ploughshares, Poetry Northwest, New England Review, and other journals. Her critical writing has appeared at Colorado Review, Kenyon Review Online, and The Rumpus. She holds an MFA from the Rainier Writing Workshop and is Poetry Editor at The Rumpus.