Natalia Azarova was born in 1956 in Moscow, graduated from Moscow State University with BA in Spanish philology, and then obtained a PhD from the Institute of Linguistics at the Russian Academy of Sciences, where she currently serves as a senior fellow and head of The Center of World Poetry Studies. She started writing poetry late, but has published eight books of poetry in ten years. She has also produced a number of important translations of world poetry, including the new Russian version of Du Fu’s selected poems and the first Russian translation of the “Ode Marítima” by Fernando Pessoa; the latter was awarded the Andrei Bely Prize in 2014.

Natalia Azarova was born in 1956 in Moscow, graduated from Moscow State University with BA in Spanish philology, and then obtained a PhD from the Institute of Linguistics at the Russian Academy of Sciences, where she currently serves as a senior fellow and head of The Center of World Poetry Studies. She started writing poetry late, but has published eight books of poetry in ten years. She has also produced a number of important translations of world poetry, including the new Russian version of Du Fu’s selected poems and the first Russian translation of the “Ode Marítima” by Fernando Pessoa; the latter was awarded the Andrei Bely Prize in 2014.

Ming Di: It was nice meeting you last year at our translation workshop in Beijing. And thank you for spending time to talk about your poetry and translation by email. You are a scholar and experimental poet at the same time and your work is fascinating to me. Can you tell me how you started writing poetry? Who has influenced you and how?

Natalia Azarova: My journey to poetry was atypical. I think it would be hard to find many poets that started writing as late as I did. I can say that until age 45 I had not even attempted to write a poem, nor in my youth. Once I even refused to do an assignment on translating Shakespeare for I felt that at 14 I would not be able to do the work any justice. After an extensive battle with the teacher I convinced him that it was not a good idea to have schoolchildren, capable of writing poems of poor quality only, to translate great poets. Perhaps a certain level of perfectionism is to be blamed. For many years I was a researcher, educator, businesswoman living in a variety of countries but all this time something in the back of my mind told me that I was a poet. But to a poet it was not necessary to be writing poems. Poetry is supposed to be freedom in terms of interactions with objects and the world. And this freedom is more important even than the ease with which one uses language. In 2003 I returned to Russia to do research work and simultaneously began to be published as a poet, suddenly finding myself in the centre of Russian Poetic life. As far as poets that have had the biggest impact on my writing, I would have to say, Paul Celan.

MD: How did Paul Celan influence you? I suppose you read him in German since you know so many languages. Does being a linguist make you more experimental as a poet?

NA: Paul Celan for me is a poet who despite all the attempts of XX century to reject the concept of truth never does it. For example, he says: A poem, if it’s a true poem, is conscious of uncertainty of its origins. To approach it with fixed firm attitudes means in the best case to attempt to anticipate something that in a poem becomes an object of, by no means, assertive search.

Yes, I read him in the original, but I enjoy most reading his poetry in two languages simultaneously: in German and in his authorized French translation, hovering between two languages.

Many people reproached Celan for writing in his own language but I think that any good poetry can be defined ex adverso—when people think that there is no way to communicate like this with a language.

I don’t think that being a linguist has influenced my poetry writing. Every poet is a linguist that cogitates language, although not discretely or objectively.

MD: In Russia, do you expect readers to read your poetry or listen to you reading aloud? You play with words on multiple levels, semantics, syntax, and sound (I’m not sure about morphology since I don’t know Russian). Last year in China you read your long poem with images projected on the screen and music in the background. What do you do if no equipment is available?

NA: I know people who consider that my work must be read with the eyes, and even claim that it has a therapeutic effect, while others say that until they hear how I read the poems out loud, they are unable to grasp the full meaning. My poetry is holistic and multilayered simultaneously. I build my poems in such a way that one can appreciate them on any level they choose, either delving to all the layers, or choosing only a few, and still the poem will function. This depends as much on the physiological preferences of the audience, weather reading or listening, as on the environment of the performance (if it is a performance). I prefer to perform in large spaces, for the poetry to sound monumental, in these cases it is necessary to involve amplification, but at the same time reading in small cafes, where you can see the faces of all the listeners, without a microphone, can allow the voice to work in a more pure form.

I like doing collective projects as well. I have a series of compositions written in collaboration with musicians, as well as poems that were later adapted to be read over sound. My son, Peter Kolpakov is a composer that has written music for the Red Cranes, and Brazil poems that we perform together. No less important is collaborating with visual artists, not only as an accompaniment to readings, but also in creating books, in which the artistic and poetic sides are equal. My husband Alexey Lazarev and our friend B. Konstriktor have both worked with me to accomplish this.

MD: Your poems can function alone as poems. Do you think by working with musicians and visual artists you are adding dimensions to your poetry? Or are you trying to redefine “poetry”?

NA: Yes, I completely agree. My poems can function alone as poems. For me poetry is never closed, it can open to music, to visual arts and can be redefined this way. I don’t think it adds something to poetry. For me it’s a new way of communication.

MD: In this particular long poem, “Red Cranes in Gray Background”, that you wrote while traveling along the Yangtze River passing my hometown Wuhan, you describe the Red Cranes (machines) you saw on a cloudy day and what went through your mind. What’s interesting is the way you make non-existing words sound so normal (by reading them so seriously) and the way you make the floating sentence structure that each part can be reverted or moved around (It’s a big challenge to translate the first part into Chinese but I really enjoyed it—to make non existing words sound normal. I’m sorry there is no English version to show to the English readers but it’s better to imagine it since a normal translation would have ruined it.) Is there a tradition of this type of poetry in Russian literature?

NA: There is a big tradition of experimental poetry in Russia, primarily the futurists, such as Khlebnikov, but they mainly experimented with words, less with the syntax and structure of the text. On the other hand, the new words that the futurists created were intended to agitate the public and accent their novelty. Similarly modernist poetry for which ‘newness’ was a primary value. For myself I attempt to disguise novelty in my work, perhaps a strange skill, but many people reading my poetry do not notice the violations of conventional speech patterns, though they are present and are relatively common in my work. At the same time, floating sentence structure is not just a device, it best reflects, in my opinion, the being of the contemporary subject, and the spatial interactions in which they exist. Furthermore this is also a female way of seeing things, the ability of peripheral vision and seeing many things happen simultaneously, freely sliding from the corporeal to the political, industrial to nature and back again. But lately I have been encountering sliding texts in many poems by younger writers in their 20s and 30s, and this makes me happy.

MD: Khlebnikov was not translated into Chinese. Mayakovskiy was but not the futurist element. There is no futurist literature in China. There are very few poets in mainland China experimenting with sound or form. More in Taiwan. You probably have noticed it since you are editing and co-translating an anthology of contemporary Chinese poetry into Russian. In China, Pushkin from the Golden Age and other Russian poets from the Silver Age have been well introduced. What’s after them that’s interesting to you? And what’s the most peculiar phenomenon in Russian poetry today?

NA: I think that today the Russian social poetry from the middle of 19th century is becoming more relevant, that which we before considered too didactic, for instance Nicolai Nekrasov. On the contrary certain writers of the silver age seem overly theatrical. Still I find the work of Mandelstam, Mayakovskiy, and Pasternak, are relevant to me, primarily their rhythmic idiosyncrasies and their use of polyrhythm and the ability to juxtapose words in such a way that in their interaction, something new is added to the world. Out of the poets of the second half of the 20th century, Boris Slutskiy whom we are now rediscovering, and Genadiy Aigi, with whom I was a friend in the last years of his life, and after his death I published a reconstruction of poems from his notebooks.

MD: Some of Aygi’s poems have been translated into Chinese by Song Lin with the help of a sinologist. He doesn’t know Russian (nor English at the time of translating the poems) but it’s through his “imperfect” translation that we find a completely new voice. Aygi’s native language is Chuvash. Do you think it makes a difference in poetry when one speaks more than one language?

NA: Yes, and I think it’s a very contemporary thing, bilingual poetry or poetry written by bilinguals. I think it’s worthwhile to hold festivals of bilingual poetry.

MD: Thank you for coming to Beijing last year for the translation workshop, a project that promotes literary exchange through “poets translating each other.” What’s your general impression of Chinese language that you find interesting? And what did you do with the work of classical ancient poet Du Fu? Can you give an example of how you play with language in Russian as a translator?

NA: Text and language of the original stimulate the translator to transform it into his/her language, and this is especially important when dealing with a non-cognate language, such as Chinese. It’s a great challenge for me to find the points of closeness between two very different languages and systems of thinking. I try not only to translate Du Fu to Russian but also translate Chinese language itself to Russian language, so to say transforming Russian under the influence of Chinese. The contemporary verse gives an opportunity to accentuate any kinds of similarities, especially those of visual repetition of characters or letters. The technique of anagram allows to reflect the repetition of elements of Chinese characters, and the number of words in Russian text is exactly the same as the number of characters in the Chinese original. Thus, the visual rhythm of the translation corresponds to the visual rhythm of the original, and the bilingual edition where the translation and the original are situated on the opposite pages underlines this graphical similarity.

MD: That sounds amazing. Can you give an example of how you use anagram techniques in translating Du Fu into Russian?

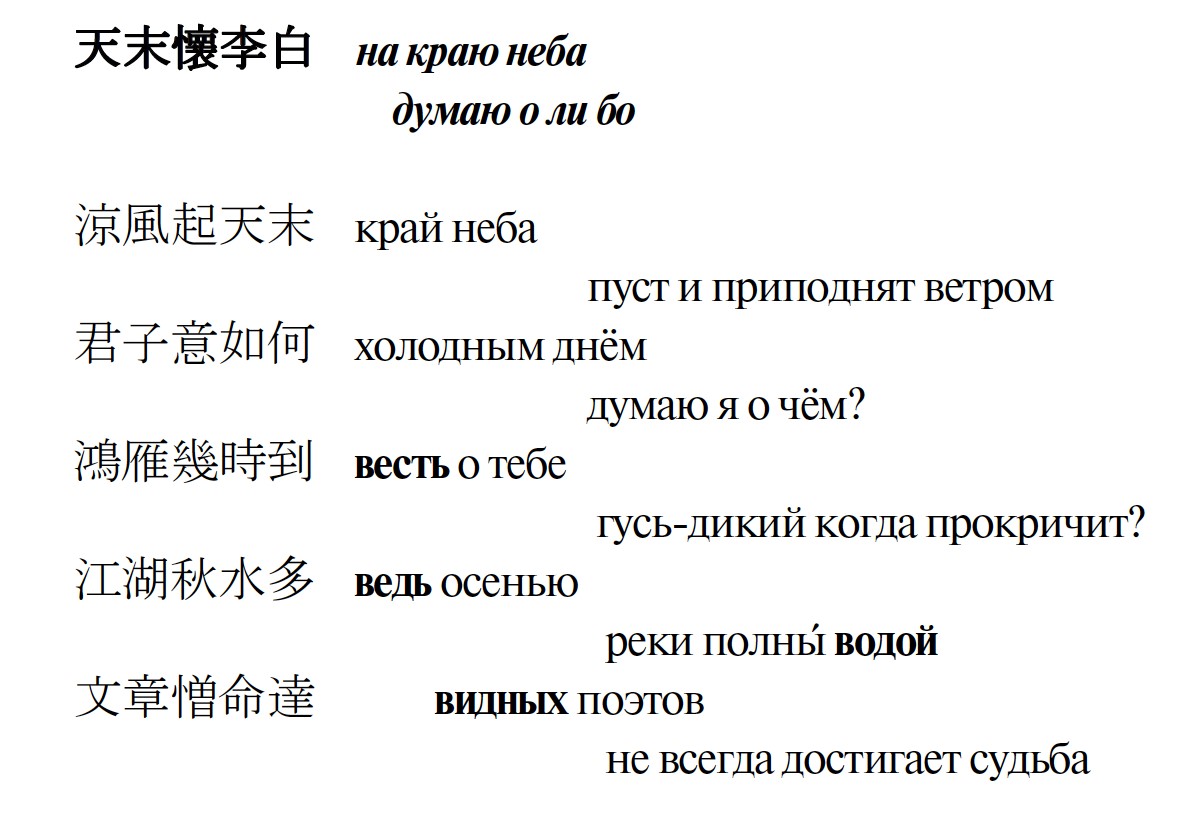

NA: It is quite a research and it requires a lot of explanations. Here is one example, the first five lines of an eight-line poem by Du Fu:

In the poem I think on the edge of the sky of Li Bai, the first three characters in Line 1-3-4 show a coolness (涼), a goose (鸿), and a river (江)– all of them contain the water radical (氵). In addition, water is present as an independent character in the fourth line. If the whole characters but not the particular radicals set the graphic rhythm, this brings up the question: how obvious is the conceptualization of radicals for a Chinese reader? Most likely, for a foreign reader that rhythm is even more visible than for a native speaker. However, such a graphic rhythm does not have to come off at the conscious level. In this sense, anagrams can act as a virtually complete analogue in translation into a European language. Anagrams work both graphically (through repeated letters) and through articulation. At the same time, calligraphy in the Chinese version can enhance assimilation and the graphical rhythm. The Russian translation can convey this meaning by the anagram of water (вода), mainly at the beginning of the poem, but also in the fifth line. The word водой (water) appears at the end of the fourth line and casts back to the beginning of the line – to the word ведь (indeed). Ведь, in turn, correlates with two line beginnings – весть (message) and видно (seen). As a result, the anagrams inform the visual-literal and audial perception of water through the words ведь, весть, видных and воды.

MD: Thank you so much. Number one, I see why you traveled along the Yangtze River—that’s where Du Fu wrote this poem. Number two, I sort of see the graphical rhythm in Russian through your explanation. I’d love to hear it (next time when we meet up). Number three, it helps in translating your “Red Cranes” knowing what you do with language. Number four, Chinese speakers (at least me) are conscious of the radicals as well as the end rhymes which work the best when rhymed on a key word, in this poem for instance, 末 mo (end, or edge), 何 huo (how, in its ancient sound, the modern sound is he),and 多 duo (more) as if echoes, the end, the end, the end. Li Bai was in exile in the frontier which seemed to be the end of the world for Du Fu. Mo means “last” is space and time. For the benefits of English readers, here is a rough translation of the first four lines:

Cold wind is blowing up at the sky’s end.

I wonder how you feel, what occupies your mind.

When will the wild goose messenger arrive?

Rivers and lakes will have more autumn waves.

The issue of radicals and components of a character is more of concerns for ancient poets than modern ones but as a visual poet I’m troubled by it every day which we can talk about next time. Last question for you. You are head of The Center of World Poetry Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences. What is “World Poetry” to you? Poetry around the world through translation in Russian? Or a type of poetry that’s understood no matter in what language it’s written?

NA: I know many foreign language and I always read poetry in the original, not through translation. I feel comfortable in different parts of the world, and for me, poetry exists in a chorus of different languages, where we have a hope to look for a kind of universal language, and the technical means at our disposal may be helpful in this search. If the rhythm has a constitutive meaning for poetry, then it’s possible not to understand a language fully, but to understand poetry through the perception of rhythm. Even by eyes. For instance, G. Aigy didn’t know German but he used to look at P. Celan’s poems for a long time and he was trying to guess in their visual configuration and layout the greater meaning.

Regarding Russian poetry, the question about up to which point the national culture relies on the bases unique for the whole world and up to which it is nourished by its own roots were debated for a very long time. The relationship between ours and theirs in the world poetry is ambiguous, our won system always misses something and we have a task to see in theirs something close and important to us, and then to understand how to build into our system of culture. To overcome the border between ours and theirs this is the contemporary idea that is meant to cancel the contradiction between the first and the last part of your question.

Two poems by Natalia Azarova

[me being a feline bird…]

me being a feline bird

dappled with sunny slaps

slippped on the lent of cheerful

thoughts

and what is your purpose so well getting on?

and what is your purpose being healthy and gay?

vessels of current time-matching with carried

quilts

sandpipers and seagulls’ sandpies

[– I’ll tuck the horizon under my heels –]

– I’ll tuck the horizon under my heels –

for we are cuddled in the sea’s warmth

– beware: someone’s throwing burning butts

from the upper deck

– ye, right: that’s august shooting stars

– our boat: is thoroughly disinfected

from said stars burnt smell

– formally: I know that Thou art but a mere tradition

but Thy temporary friendship I won’t mind

© English translation of the two poems by Peter Kolpakov